The United States’ largest offshore fossil fuel production basin has twice the climate warming impact as official estimates, report researchers.

The work could have bearing on future energy production in the Gulf of Mexico, as decisions about expanding oil and gas harvesting depend on calculations of the climate impact.

While a gap between reported and measured methane emissions in the basin has been noted in the past, this study may be the first to quantify methane and carbon dioxide emissions and identify the main culprits. It turns out older platforms located closer to land emit far more methane than is reported in government inventories.

Simple steps could go a long way in mitigating those releases, the researchers say.

To conduct their atmospheric measurements, the researchers flew upward and downward in a cylindrical pattern around the platforms and measured amounts of both carbon dioxide and methane being released. They combined aircraft measurements with all previous field surveys to gather the largest sample size of Gulf of Mexico platform GHG emissions. Their observations quickly put a spotlight on certain oil and gas producing operations.

“What we found is that a certain type of shallow water platform had large methane emissions that elevated total greenhouse gas emissions for the entire Gulf of Mexico,” says Eric Kort, associate professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan, principal investigator of the F3UEL project, and corresponding author of the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“So if we can direct mitigation efforts at those sources to address the problem, it could have a huge positive effect.”

These sources are larger “central-hub” multiplatform complexes that collect oil and gas from small production platforms for processing. Sampling showed these emit more methane than expected, due to direct venting into the atmosphere or releases from tanks and other equipment.

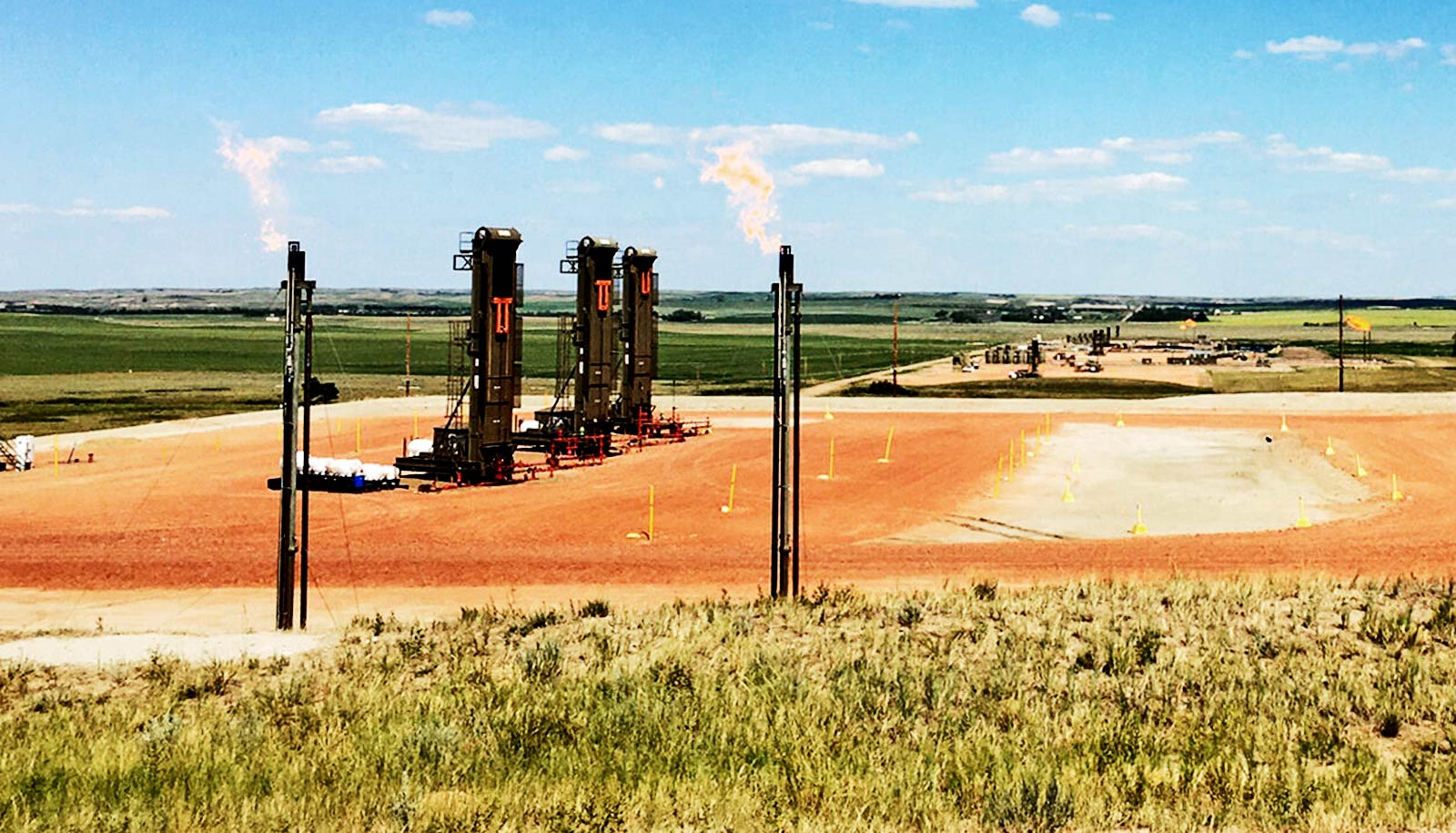

Actions to address these large methane emissions, whether through capturing the gas, flaring it instead of venting, or repairing or abandoning of facilities, could have outsized climate benefits.

The finding is similar to research the same team published in September that showed inefficient flaring operations on land were releasing five times more methane into the atmosphere than expected. Together, these studies demonstrate the need for a more comprehensive way of assessing greenhouse gas emissions, and thus the climate impact of oil and gas production for a given region. Climate impact is determined by “carbon intensity,” a metric for the levels of greenhouse gasses that are emitted per unit of oil or gas produced.

When new oil and gas projects are under consideration, regulators assess whether the new builds will have the same or lower than the carbon intensity of expanded production elsewhere. This has already affected decisions about oil and gas lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico. However, in these assessments, estimates of the carbon dioxide and methane released into the atmosphere have not historically been based on direct measurements, and many of them have not included methane emissions.

“We have presented the climate impact of both oil and gas production as an observation-based carbon intensity,” says Alan Gorchov Negron, a graduate student research assistant and the study’s first author. “This metric reflects a snapshot of real-time climate impacts and offers an easy way to integrate the growing number of field surveys of emissions from fossil fuel production into a consistent metric.

“Moving forward, policy or investment decisions can use consistent metrics such as this to choose fossil fuels from locations that minimize their climate impacts.”

The study also involved researchers from Stanford University, Scientific Aviation, Carbon Mapper, and the Environmental Defense Fund. The research had funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation with additional support from Environmental Defense Fund, Scientific Aviation, and the University of Michigan’s department of climate and space sciences and engineering and Graham Sustainability Institute.

Source: University of Michigan