The same proteins that moderate nicotine dependence in the brain may be involved in regulating metabolism by acting directly on certain types of fat cells, new research shows.

Researchers had previously identified a new type of fat cell in mice and humans, in addition to the white fat cells that store energy as lipids. These thermogenic, or “beige” fat cells can be activated to burn energy through a process called thermogenesis.

“It is really cool to discover a selective pathway for beige fat, a new cell type—and even more exciting that this is conserved in humans.”

To better understand what makes beige fat unique, researchers analyzed activated beige fat and uncovered a molecule directly linked to thermogenesis in these cells: CHRNA2 (for cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 2), a type of receptor that is best known for regulating nicotine dependence in brain cells.

The findings, which appear in Nature Medicine, reveal that CHRNA2 functions in mouse and human beige fat cells, but not in energy-storing white fat cells—indicating that the protein plays a role in energy metabolism.

This doesn’t mean that smoking is good for you, says Jun Wu, a research assistant professor at the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute. But the findings may further explain some of the weight gain that is associated with smoking cessation.

Research has shown that nicotine can suppress appetite. By identifying how nicotine affects metabolism directly, the findings may open the door to new ways to fight the weight gain that often occurs when someone stops smoking.

In research conducted in human and mouse cells and in genetically modified mice, Wu and colleagues determined that CHRNA2 receptor proteins can be activated both by nicotine and by acetylcholine molecules nearby immune cells produce. When the CHRNA2 protein receives the acetylcholine or nicotine, it stimulates the beige fat cells to start burning energy.

“It is really cool to discover a selective pathway for beige fat, a new cell type—and even more exciting that this is conserved in humans,” says Wu, the study’s senior author and assistant professor of molecular and integrative physiology.

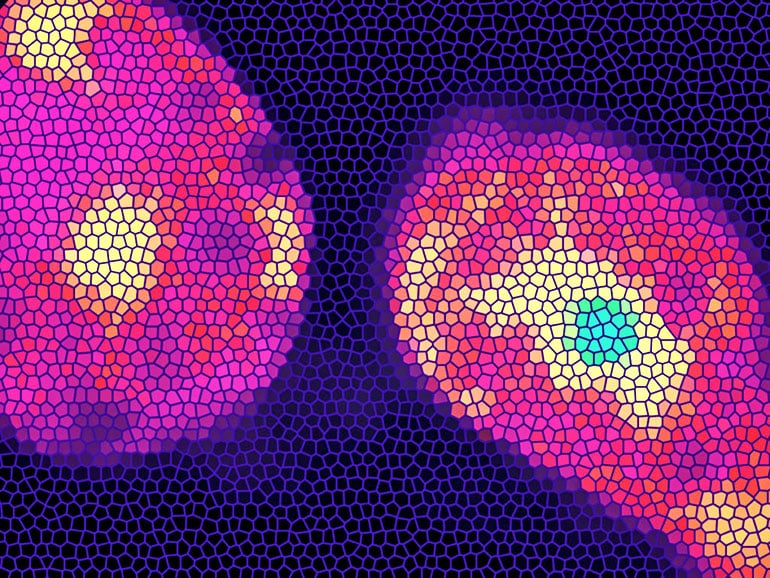

3D images of fat reveal new targets in obesity fight

To further test the role of CHRNA2 in metabolism, researchers analyzed mice that lacked the gene needed to make this protein. “And the mice definitely are metabolically worse off, compared to the control group,” Wu says.

Mice without the CHRNA2 gene showed no differences from the control group when researchers fed them a regular diet. But when they were switched to a high-fat diet, the mice lacking the gene exhibited greater weight gain, higher body fat content, and higher levels of blood glucose and insulin—indicators of diabetes.

“Beige fat is very important in regulating whole-body metabolic health,” Wu says. “Our results in mice show that if you lose even one aspect of this regulation—not the whole cell function, but just one part of its function—you will have a compromised response to metabolic challenges.”

Wu believes that understanding the specific CHRNA2 signaling pathway in beige fat also opens a new avenue for identifying druggable targets to treat obesity and metabolic syndrome.

“This pathway is important from a basic research standpoint, but it also has relevance for metabolic and human health research,” she says. “The more we can narrow down a precise pathway for activating beige fat, the more likely we are to find an effective therapy for metabolic health that does not carry harmful side effects.”

Lots of teens smoke to lose weight

Other researchers from the University of Michigan and from Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Central South University, and Fudan University, all in China, are coauthors of the paper.

The Human Frontier Science Program, Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, and National Institutes of Health funded the work.

Source: University of Michigan