New findings in mice are a step closer to finding a possible target for treating neuropsychiatric disorders like schizophrenia and autism in young adulthood.

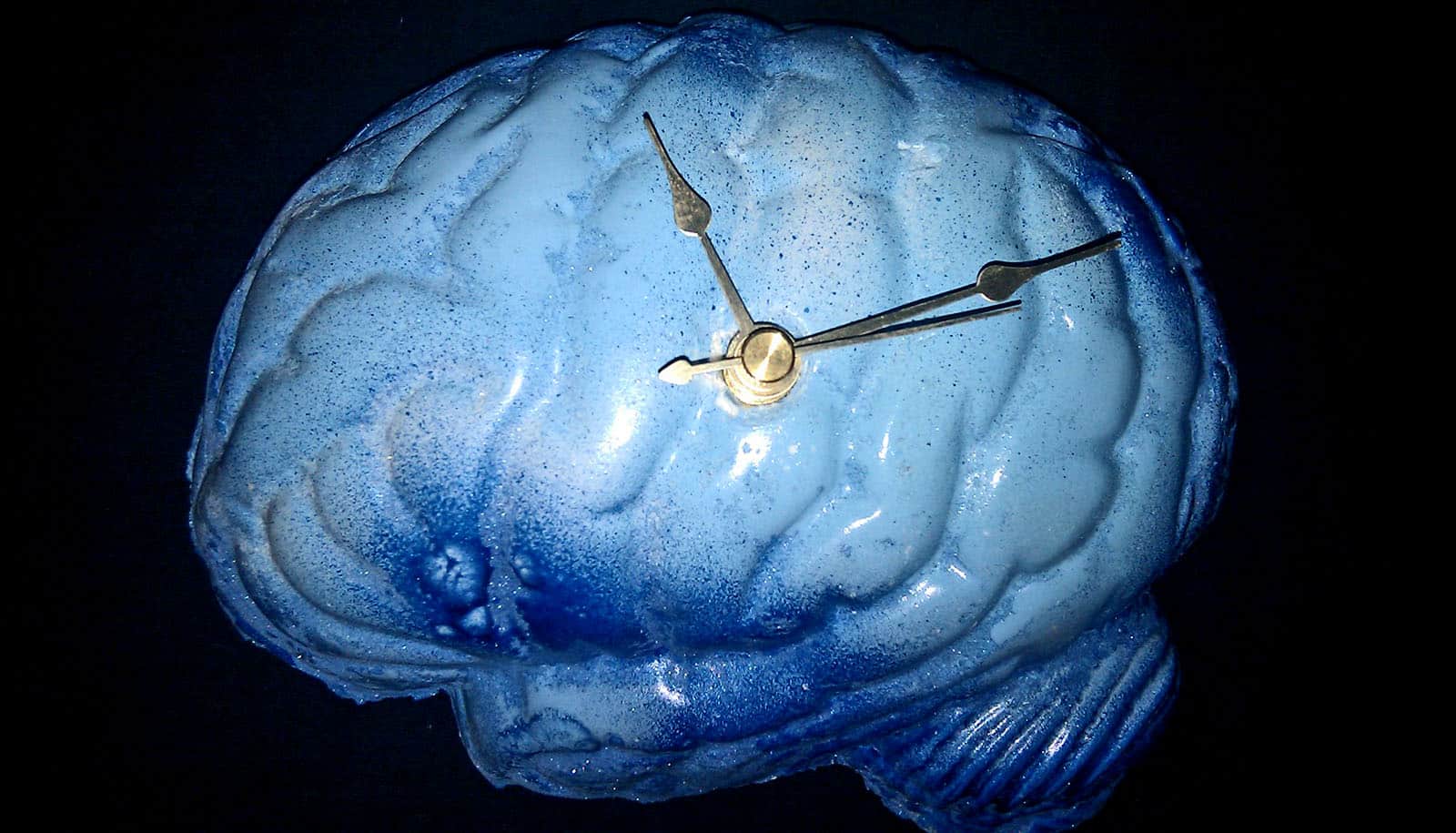

The brain continuously changes during childhood and throughout adolescence. The onset of neuropsychiatric disorders like schizophrenia often begins during young adulthood. Dysfunction of the dopamine system—necessary for cognitive processing and decision-making—begins during this point in development.

“Brain development is a lengthy process, and many neuronal systems have critical windows—key times when brain areas are malleable and undergoing final maturation steps,” says Rianne Stowell, a postdoctoral fellow in the Wang Lab at the University of Rochester Medical Center and co-first author of a new study in the journal eLife.

“By identifying these windows, we can target interventions to these time periods and possibly change the course of a disease by rescuing the structural and behavioral deficits caused by these disorders.”

Researchers targeted underperforming neurons in the dopamine system that connect to the frontal cortex in mice. This circuitry is essential in higher cognitive processing and decision-making. They found that stimulating the cells that provide dopamine to the frontal cortex strengthened this circuit and rescued structural deficiencies in the brain that cause long-term symptoms.

Previous research from the Wang Lab identified that this specific arm of the dopamine system was flexible in the adolescent brain but not in adults. This most recent research used this window for plasticity in the system as an opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

“These findings suggest that increasing the activity of the adolescent dopaminergic circuitry can rescue existing deficits in the circuit and that this effect can be long-lasting as these changes persist into adulthood,” Stowell says. “If we can target the right windows in development and understand the signals at play, we can develop treatments that change the course of these brain disorders.”

Additional collaborators are from the University of Rochester Medical Center; the National Institute of Mental Health; and the University of Pennsylvania. This research had support from the National Institutes of Health and the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience pilot program.

Source: University of Rochester