A new machine learning model that predicts interactions between nanoparticles and proteins is a step toward engineered nanoparticles that fight infection.

The rise of antibiotic resistance motivates the researchers.

“We have reimagined nanoparticles to be more than mere drug delivery vehicles. We consider them to be active drugs in and of themselves,” says J. Scott VanEpps, assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan and an author of the study in Nature Computational Science.

Discovering drugs is a slow and unpredictable process, which is why so many antibiotics are variations on a previous drug. Drug developers would like to design medicines that can attack bacteria and viruses in ways that they choose, taking advantage of the “lock-and-key” mechanisms that dominate interactions between biological molecules. But it was unclear how to transition from the abstract idea of using nanoparticles to disrupt infections to practical implementation of the concept.

“By applying mathematical methods to protein-protein interactions, we have streamlined the design of nanoparticles that mimic one of the proteins in these pairs,” says Nicholas Kotov, professor of chemical sciences and engineering and corresponding author of the study.

“Nanoparticles are more stable than biomolecules and can lead to entirely new classes of antibacterial and antiviral agents.”

The new machine learning algorithm compares nanoparticles to proteins using three different ways to describe them. While the first was a conventional chemical description, the two that concerned structure turned out to be most important for making predictions about whether a nanoparticle would be a lock-and-key match with a specific protein.

Between them, these two structural descriptions captured the protein’s complex surface and how it might reconfigure itself to enable lock-and-key fits. This includes pockets that a nanoparticle could fit into, along with the size such a nanoparticle would need to be. The descriptions also included chirality, a clockwise or counterclockwise twist that is important for predicting how a protein and nanoparticle will lock in.

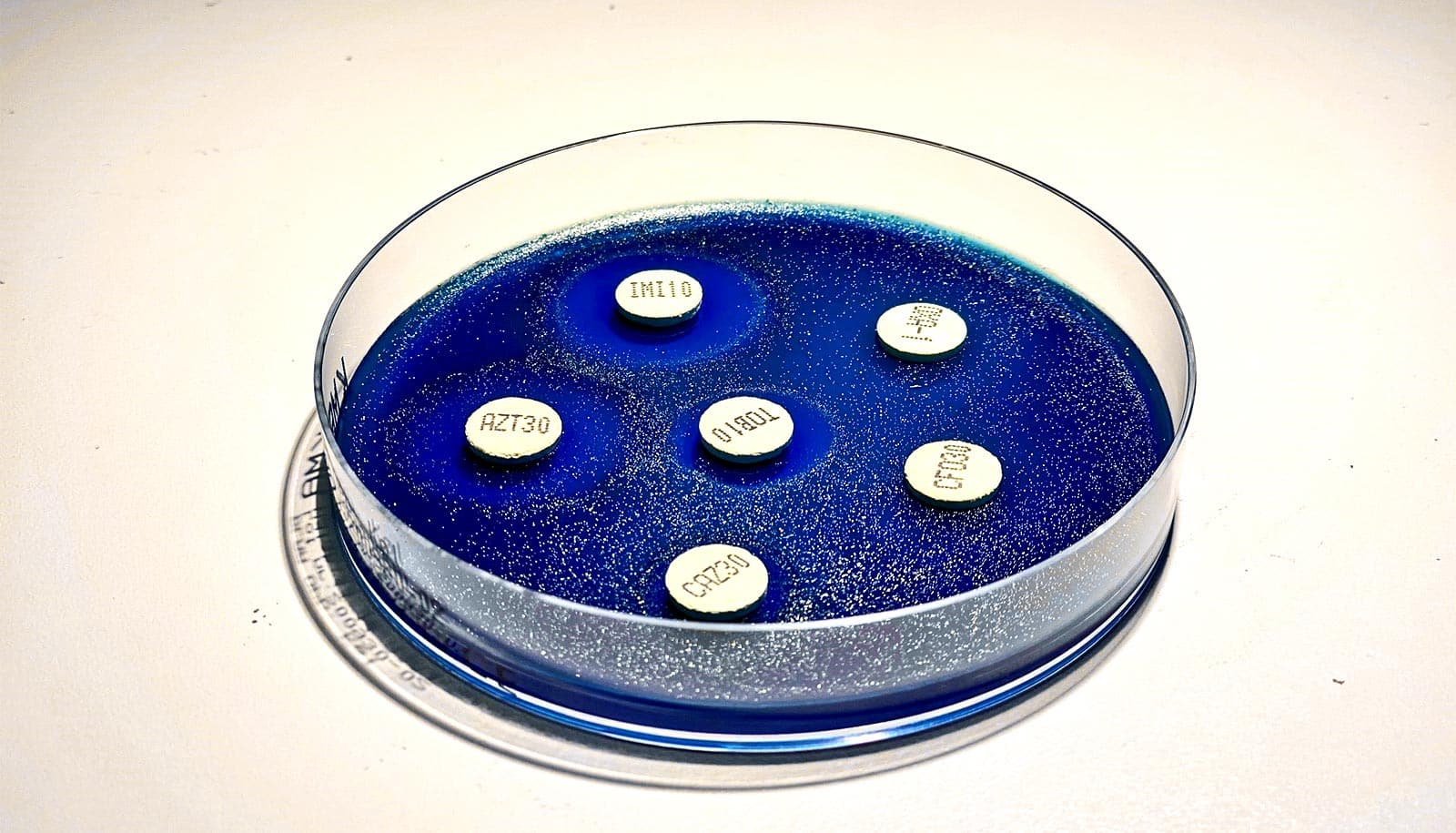

“There are many proteins outside and inside bacteria that we can target. We can use this model as a first screening to discover which nanoparticles will bind with which proteins,” says Emine Sumeyra Turali Emre, a postdoctoral researcher in chemical engineering and co-first author of the paper, along with Minjeong Cha, a PhD student in materials science and engineering.

Emre and Cha explained that researchers could follow up on matches identified by their algorithm with more detailed simulations and experiments. One such match could stop the spread of MRSA, a common antibiotic-resistant strain, using zinc oxide nanopyramids that block metabolic enzymes in the bacteria.

“Machine learning algorithms like ours will provide a design tool for nanoparticles that can be used in many biological processes. Inhibition of the virus that causes COVID-19 is one good example,” Cha says. “We can use this algorithm to efficiently design nanoparticles that have broad-spectrum antiviral activity against all variants.”

Support for this project came from the University of Michigan College of Engineering’s Blue Sky Initiative, the Office of Naval Research, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. Collaborators at the University of California, Los Angeles contributed to the machine learning algorithm.

Source: University of Michigan