The moon may have formed through Earth’s collision with close neighbor, a new study finds.

One bright day on Earth about 4.5 billion years ago, everything changed.

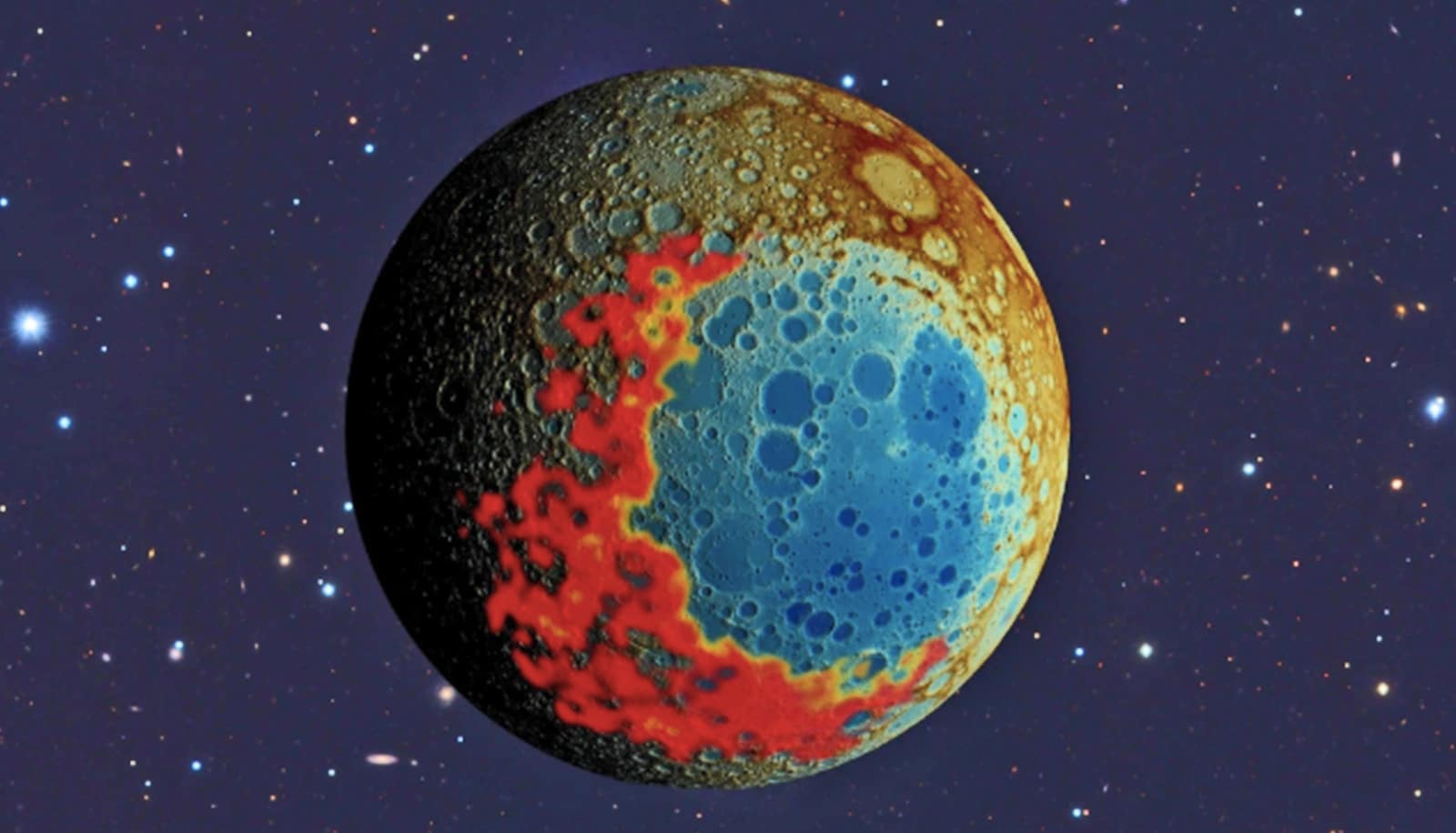

A massive object slammed into the young planet. The impact was so large that bits were flung out into space, eventually coalescing into the moon that has kept us company ever since.

We know that much. What we don’t know is everything else—including the size of this object, what it was made of, and where it came from. These questions have been hard to answer, because the object, nicknamed Theia, was completely destroyed in the collision.

But by analyzing moon rocks brought back by the Apollo missions, researchers believe they’ve deduced what Theia was made of—and thus its place of origin.

The results, from a team of scientists with the University of Chicago, Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, and the University of Hong Kong appear in Science.

“The most convincing scenario is that most of the building blocks of Earth and Theia originated in the inner solar system,” says lead study author Timo Hopp, former postdoctoral researcher at UChicago and now a scientist with the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

“Earth and Theia are likely to have been neighbors,” he says.

Written into the rocks of every celestial object—Earth, the moon, meteors, stars—is the story of its formation.

The trouble is decoding that information. The language it’s written in is isotopes: the minor variations of elements that very slightly change their atomic weights.

These isotopes are forged in stars. However, studies from the University of Chicago and other institutions have shown that once that material was ejected by stars, it never fully mixed within our solar system.

“As a result, different regions inherited distinct isotopic proportions, which now serve as a fingerprint to trace the origins of meteorites and other celestial bodies,” explained Professor Nicolas Dauphas, formerly at UChicago and now at the University of Hong Kong.

For years, scientists have wondered about the Theia-Earth collision. Was the moon formed exclusively from Theia, or was it mostly material that was flung off Earth’s mantle? Or did these rocks mix inseparably during the collision?

Separating out the isotopes to answer these questions, however, is an extremely difficult task. Isotopes vary by only the weight of a few neutrons, and the samples we have of the moon are tiny and precious—so the precision required is extraordinary.

Dauphas’ laboratory specializes in developing new techniques to precisely measure these isotope ratios.

The team analyzed terrestrial rocks, six lunar samples, and samples of meteorites that have come from the different areas of the solar system where Theia might have formed.

They made precision measurements of the iron in the samples, and combined that with previously measured isotope ratios of chromium, calcium, titanium, molybdenum, and zirconium.

Then they rolled this into their knowledge about how these metals behave differently in planetary processes. For example, early Earth’s iron and molybdenum likely mostly formed the iron core of the planet before it was struck. That means that a significant fraction of iron found in Earth’s crust and mantle today probably came from Theia.

Inferences like these allowed the team to narrow down the story. They also ran simulations to understand which compositions of Theia would have led to these ratios.

According to the calculations, Theia wasn’t a visitor from deep space. In fact, it likely originated closer to the sun than our planet did—the group of meteorites that most closely match Theia’s ratios comes from the zones of the solar system close to the sun.

“During the early solar system’s game of cosmic billiards, Earth was struck by a neighbor,” says Dauphas. “It was a lucky shot. Without the moon’s steadying influence on our planet’s tilt, the climate would have been far too chaotic for complex life to ever flourish.”

Funding for the work came from NASA, National Science Foundation, US Department of Energy, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaf, European Research Council.

Source: University of Chicago