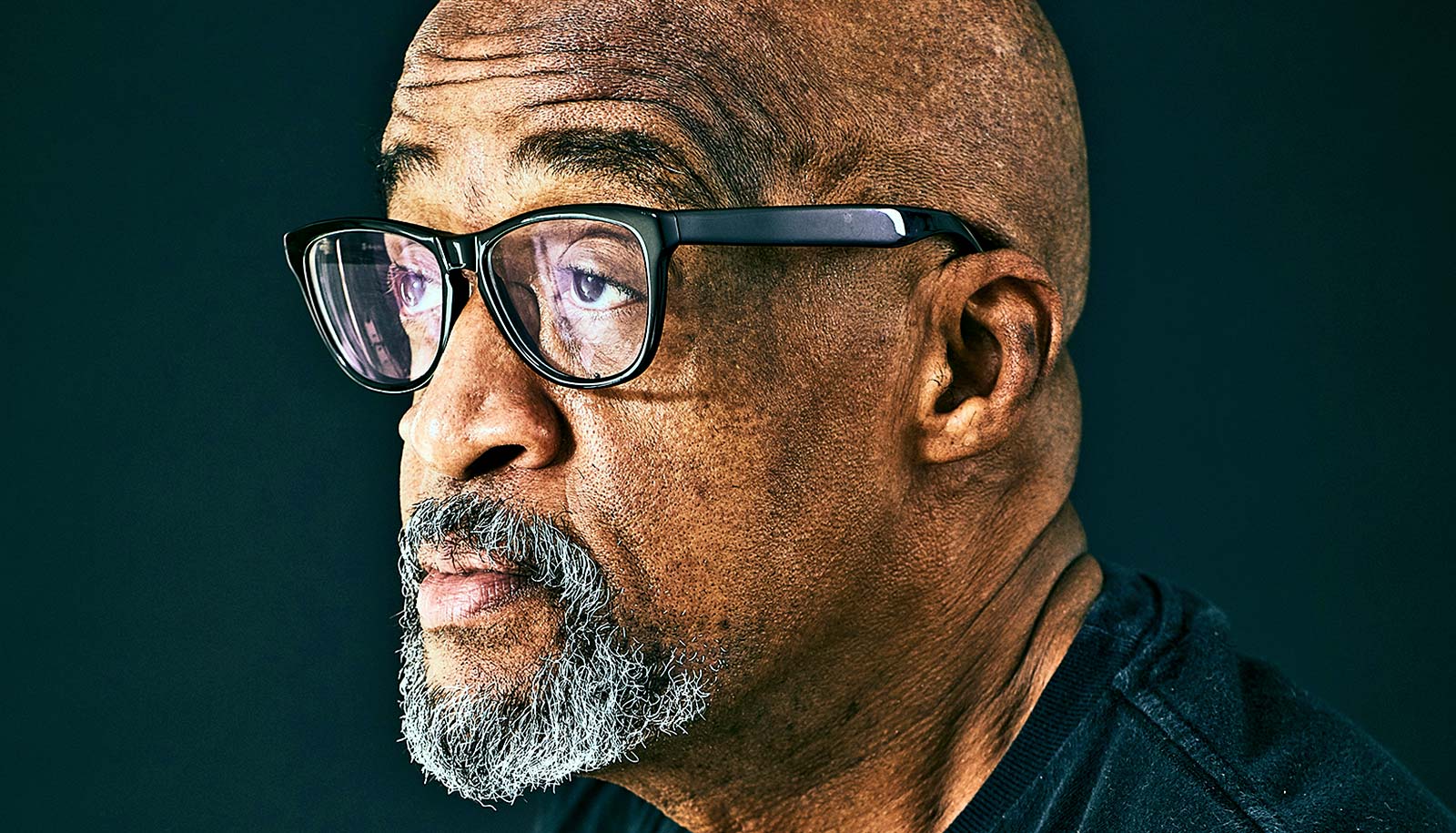

New research may explain why some older adults without noticeable cognitive problems have a harder time than younger people in separating irrelevant information from what they need to know at a given time.

The findings offer an initial snapshot of what happens in the brain as young and old people try to access long-term memories, and could shed light on why some people’s cognitive abilities decline with age while others remain sharp.

“Your task performance can be impaired not just because you can’t remember, but because you can’t suppress other memories that are irrelevant,” says senior author Susan Courtney, a cognitive neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University. “Some ‘memory problems’ aren’t a matter of memory specifically, but a matter of retrieving the correct information at the right time to solve the problem at hand.”

The researchers had 34 young adults (18 to 30) and 34 older adults (65-85) perform a mental arithmetic task while researchers measured their brain activity through functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. Researchers also collected other images to measure the integrity of the connections between brain areas called white matter tracts.

The task compared the participants’ ability to inhibit irrelevant information automatically retrieved from long-term memory. Researchers asked participants to indicate whether a proposed solution to an addition or multiplication problem was correct or not—for instance 8×4=12 or 8+4=32. These examples would create interference as participants considered the right answer because although they should answer “incorrect,” the proposed solution seems correct at first glance, based on long-term memories of basic math.

This interference did not exist when researchers asked participants to answer clearly false equations like 8×4=22. Making the task even more complicated, the researchers sometimes asked subjects to switch to multiplication after they saw the addition symbol and vice versa.

Older people were a fraction of a second slower at answering the questions than younger participants, particularly when there was interference, but the more dramatic difference showed up in the brain scans. Older individuals who had more difficulty with interference also had more frontal brain activation than young adults.

The brain imaging demonstrated that in some aging participants, fibers connecting the front and back of the brain appear to have been damaged over the years. However other older individuals had fibers similar to much younger subjects. The greater the integrity of these fibers, the better the participant’s task performance, says lead author Thomas Hinault, a postdoctoral fellow.

“Everyone we studied had good functioning memory, but still we saw differences,” Hinault says. “There are so many disruptions in the world and being able to suppress them is crucial for daily life.”

The researchers were surprised to find that during parts of the task that were the trickiest, where participants had to switch between multiplication and addition and researchers asked them to add after they saw a multiplication command or vice versa, the people with the strongest brain fiber connections counterintuitively performed even better. Something about deliberately exercising the mind in this fashion made the most agile minds even more so.

“If you have good connections between brain networks, that will help,” Courtney says. “If not, you have interference.”

The findings appear in Neurobiology of Aging.

Additional coauthors are from McGill University and the Université de Montréal.

Source: Johns Hopkins University