A simple question at the doctor’s office could help people with medication adherence, a new study shows.

A visit to the doctor’s office typically begins with a series of questions, including one about medications. New research recommends doctors ask a follow up to that question to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed.

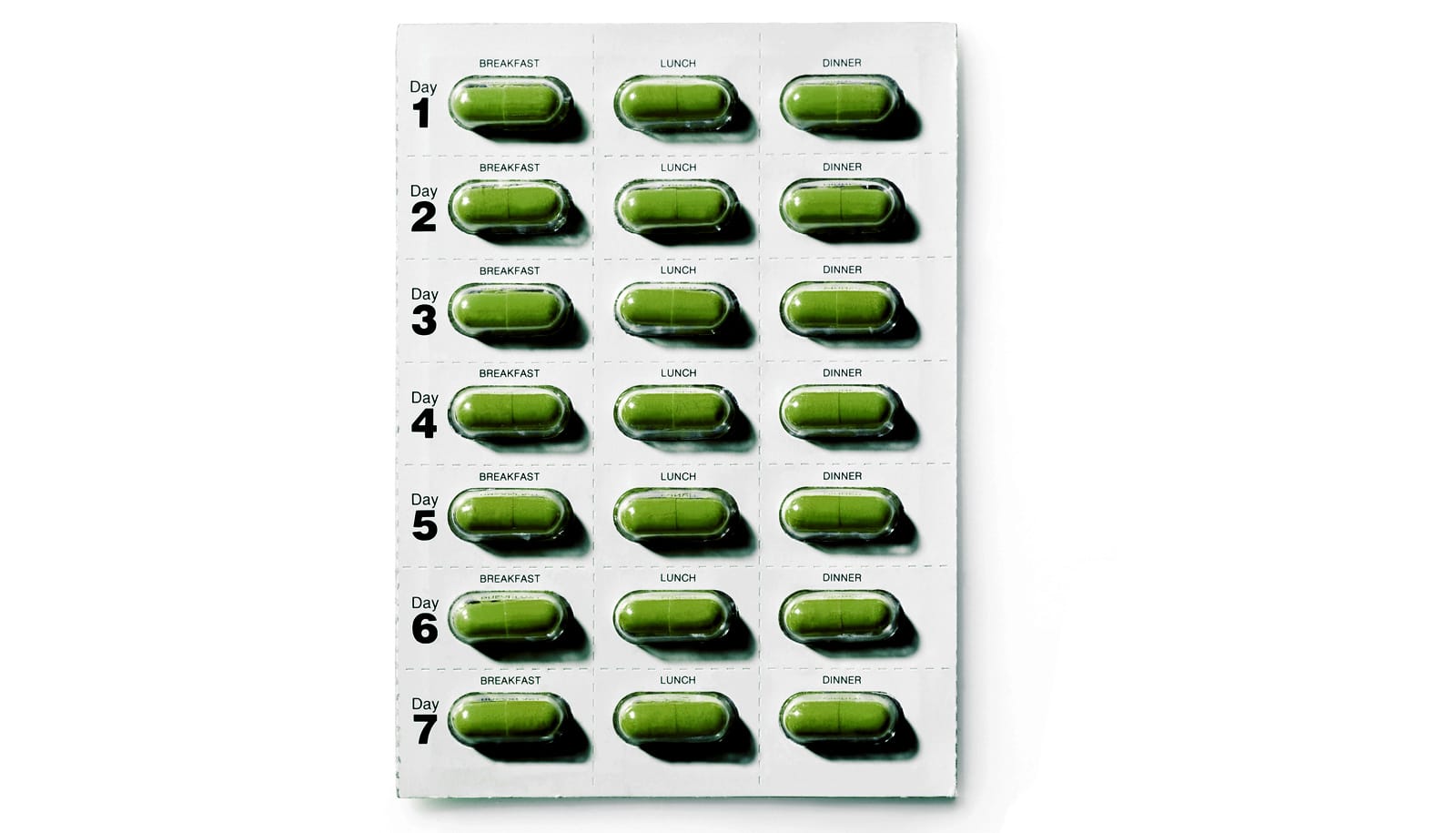

Medication adherence is vital to patient health and outcomes, says Alison Phillips, an associate professor of psychology at Iowa State University, but research shows 20 to 50 percent of patients forget or do not take their medicine for various reasons.

While doctors know adherence is a problem, they avoid asking about it, because patients struggle to recall missed pills or give an answer they think doctors want to hear rather than admit the truth, she says.

For the study, Phillips and coauthor Elise A. G. Duwe, former postdoctoral researcher in Phillips’ lab and resident physician at Northeast Iowa Family Medicine Education Foundation, tested whether doctors could effectively estimate adherence after reading transcripts of patients’ descriptions of their medication routine.

As reported in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, doctors are as accurate in estimating patients’ adherence as patients are in reporting the medications they had taken.

“Most doctors do not discuss adherence with their patients, but they should,” Phillips says. “If it’s too uncomfortable to ask if they’re taking their medications, doctors should ask patients about their habits. It can offer insight on adherence or at the very least be a conversation starter for a topic normally not addressed.”

‘Take it very first thing’

Researchers asked patients in the study to describe their daily routine for taking medication and to recall how many days during the last week they missed a pill. They used a medication monitoring system to track compliance for the following month. The system attaches to a pill bottle and records the date and time when a patient opens the bottle. Of the 156 patients, 75 took a pill for hypertension, the other 81 took medication for type-2 diabetes.

The researchers shared examples of how patients described their medication-taking routines. A patient with high adherence: “Get up, take it very first thing because must be time lag between taking it and eating. Then shower and shave then eat.” A patient with low adherence: “I take it twice a day with food. I try to take it at lunch and dinner. But sometimes I slip up and end up taking at different times.”

Researchers shared this data with doctors and asked them to estimate adherence (for percentage of prescribed doses taken and percentage of doses taken on time) based on patient descriptions and recall. They then compared the estimates to adherence rates which the monitoring system calculated.

Doctors were just as good at estimating patients’ adherence from the patients’ routine descriptions as they were when estimating from patients’ direct reports of missed pills, Phillips says.

How to promote medication adherence

If patients don’t have a medication routine or habit, developing one will lessen their risk of forgetting, Phillips says. She plans to design and test interventions for doctors to share with patients they identify as less likely to adhere to build upon the research.

There are several reasons why patients do not take their medications, Phillips says. For some, cost and access is a barrier. Others do not trust medications and would rather make lifestyle changes than take a pill. Even those who accept they need the medication may think they can take a break or only take half of what is prescribed.

“With many medications, you need at least 80 percent adherence for the drug to work properly and some medications are even higher than that,” she says.

“Habit-focused interventions would target those who forget to regularly take their pills versus those who consciously decide not to take their pills. Still, if doctors ask about routines it may reveal other barriers they need to consider when prescribing medication.”

Source: Iowa State University