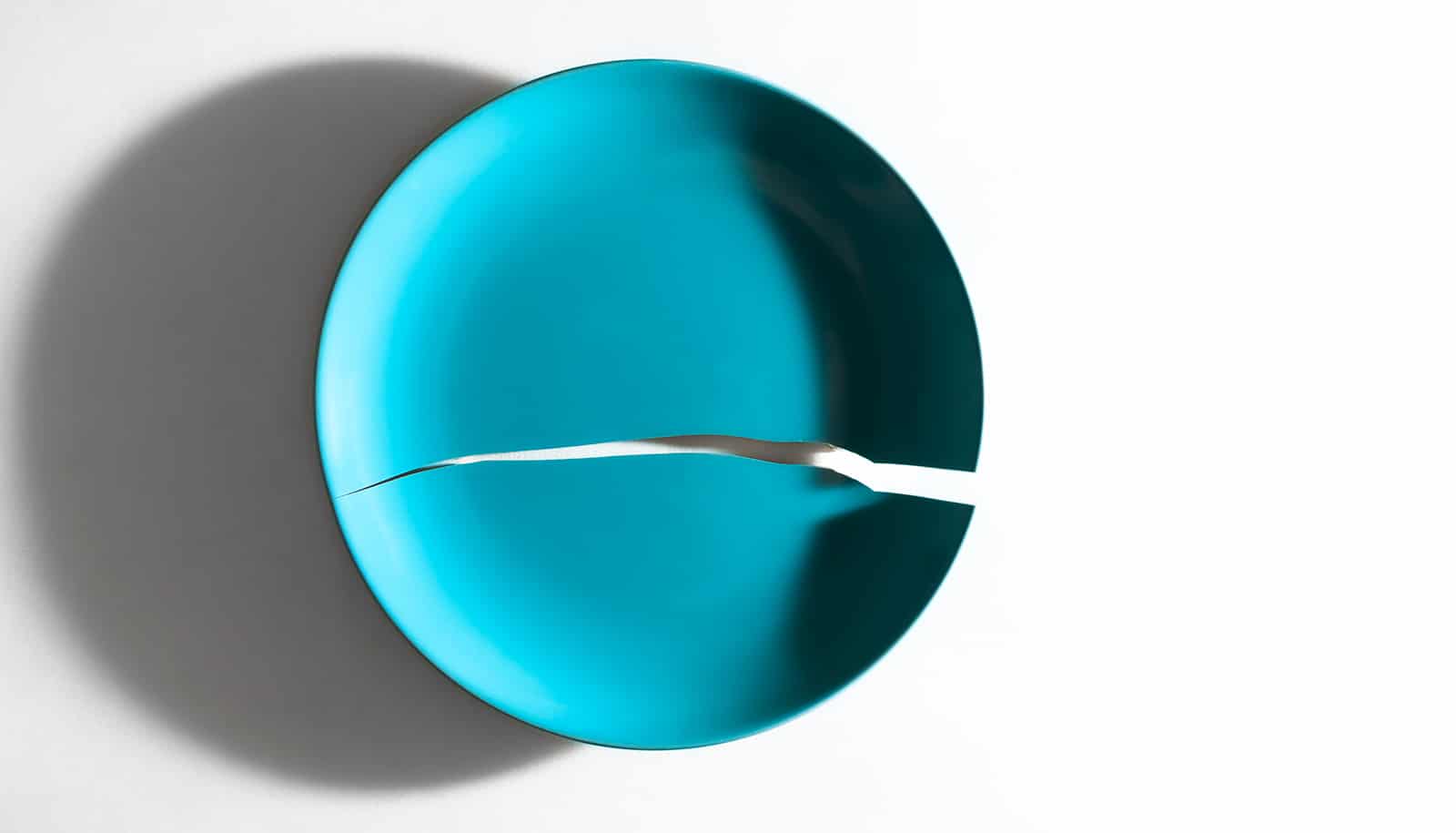

Researchers have discovered a class of ceramics called MAX phases that can self-heal cracks even at room temperature.

They’ve shown that these engineered ceramics form natural faults or kink-bands during loading that can not only effectively stop cracks from growing, but can also close and heal them, thereby preventing catastrophic failure.

“What’s really exciting about MAX phases is that they readily form kink-bands under loading which can self-heal cracks even at room temperature, making them suitable for a variety of advanced structural applications,” says Ankit Srivastava, assistant professor in the materials science and engineering department at Texas A&M University as well as a corresponding author of the study in Science Advances.

“So far, self-healing of cracks in ceramics has only been achieved at very high-temperatures by oxidation and that is why self-healing of cracks at room-temperature by kink-band formation is remarkable.”

This remarkable behavior of MAX phases ceramics can be traced back to their atomically layered structures.

“Imagine a plain loaf of bread, it is homogeneous, so if I slice it up, each slice will look the same—similar in idea to conventional ceramics,” says Miladin Radovic a professor in the materials science and engineering department and also a corresponding author of the study. “But MAX phases are layered like a peanut butter sandwich with peanut butter between two slices of bread.”

The researchers then investigated if this unique layered structure of MAX phases makes them any different from conventional ceramics. For their experiments, they used single crystal samples of chromium aluminum carbide MAX phase synthesized by senior author Thierry Ouisse of Université Grenoble Alpes, France, and loaded them inside an electron microscope using an in-house designed test fixture.

When the researchers viewed the deforming sample in the electron microscope while applying loading, they observed that there were kink-band like defects that formed in the material, resembling those formed in natural rocks.

More interesting, they discovered that the material within kink-bands rotate during loading which not only form barrier against crack propagation but also eventually close and heal the cracks. As a consequence, the sample was no longer vulnerable to catastrophic failure.

“What’s really exciting is that this kinking or self-healing mechanism can occur over and over closing the newly formed cracks, thus delaying the failure of the material,” says lead author Hemant Rathod, a doctoral student in the materials science and engineering department.

The current discovery that materials resilient to heat and extreme environments such as MAX phases, also self-heal cracks which may form during service can advance a host of next-generation technologies, for instance, efficient jet engines, hypersonic flights, and safer nuclear reactors.

The researchers also note in the current study that the kink-band induced self-healing of cracks is most likely not unique to MAX phases and can be extended to other materials with similar atomically layered structures.

“This study demonstrates the serendipity of the scientific process,” says Siddiq Qidwai, a program director in National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Engineering. “We have had self-healing soft materials and polymer composites, and now, remarkably, ceramics.”

The National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: Texas A&M University