New research suggests volcanic activity still plays an active role in shaping the surface of Mars.

Since 2018, when the NASA InSight Mission deployed the SEIS seismometer on the surface of Mars, seismologists and geophysicists have been listening to the seismic pings of more than 1,300 marsquakes.

Again and again, the researchers registered smaller and larger marsquakes. A detailed analysis of the quakes’ location and spectral character revealed a surprise.

With epicenters originating in the vicinity of the Cerberus Fossae—a region consisting of a series of rifts, or graben—these quakes tell the new surface story.

Marsquakes point to recent volcanic activity

The researchers analyzed a cluster of more than 20 recent marsquakes that originated in the Cerberus Fossae graben system. From the seismic data, the scientists concluded that the low-frequency quakes indicate a potentially warm source that could be explained by present day molten lava, i.e., magma at that depth, and volcanic activity on Mars.

Specifically, they found that the quakes are located mostly in the innermost part of Cerberus Fossae.

When they scanned observational orbital images of the same area, the researchers noticed that the epicenters were located very close to a structure that has previously been described as a “young volcanic fissure.” Darker deposits of dust around this fissure are present not only in the dominant direction of the wind, but in all directions surrounding the Cerberus Fossae Mantling Unit.

“The darker shade of the dust signifies geological evidence of more recent volcanic activity—perhaps within the past 50,000 years—relatively young, in geological terms,” explains Simon Stähler, the lead author of the new paper in Nature. Stähler is a senior scientist working in the seismology and geodynamics group led by Domenico Giardini, professor at the Institute of Geophysics at ETH Zurich.

Dry ice on polar caps

Exploring Earth’s planetary neighbors is no easy task. Mars is the only planet, other than Earth, on which scientists have ground-based rovers, landers, and now even drones that transmit data. All other planetary exploration, so far, has relied on orbital imagery.

“InSight’s SEIS is the most sensitive seismometer ever installed on another planet,” Giardini says. “It affords geophysicists and seismologists an opportunity to work with current data showing what is happening on Mars today—both at the surface and in its interior.”

The seismic data, along with orbital images, ensure a greater degree of confidence for scientific inferences.

One of our nearest terrestrial neighbors, Mars is important for understanding similar geological processes on Earth. The red planet is the only one we know of, so far, that has a core composition of iron, nickel, and sulfur that might have once supported a magnetic field.

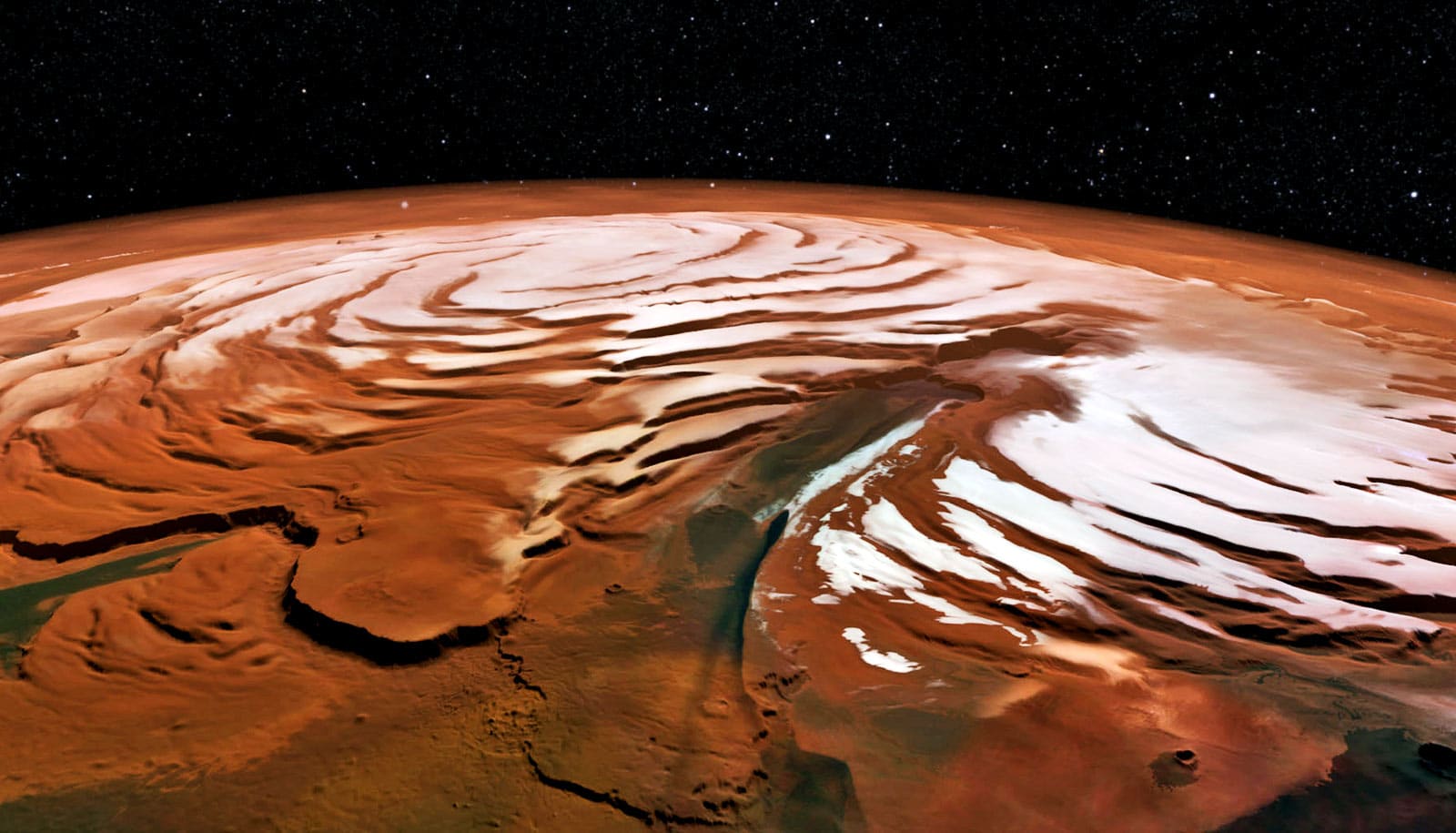

Topographical evidence also indicates that Mars once held vast expanses of water and possibly a denser atmosphere. Even today, scientists have learned that frozen water, although possibly mostly dry ice, still exists on its polar caps.

“While there is much more to learn, the evidence of potential magma on Mars is intriguing,” says Anna Mittelholz, postdoctoral fellow at ETH Zurich and Harvard University.

Not quite dead yet

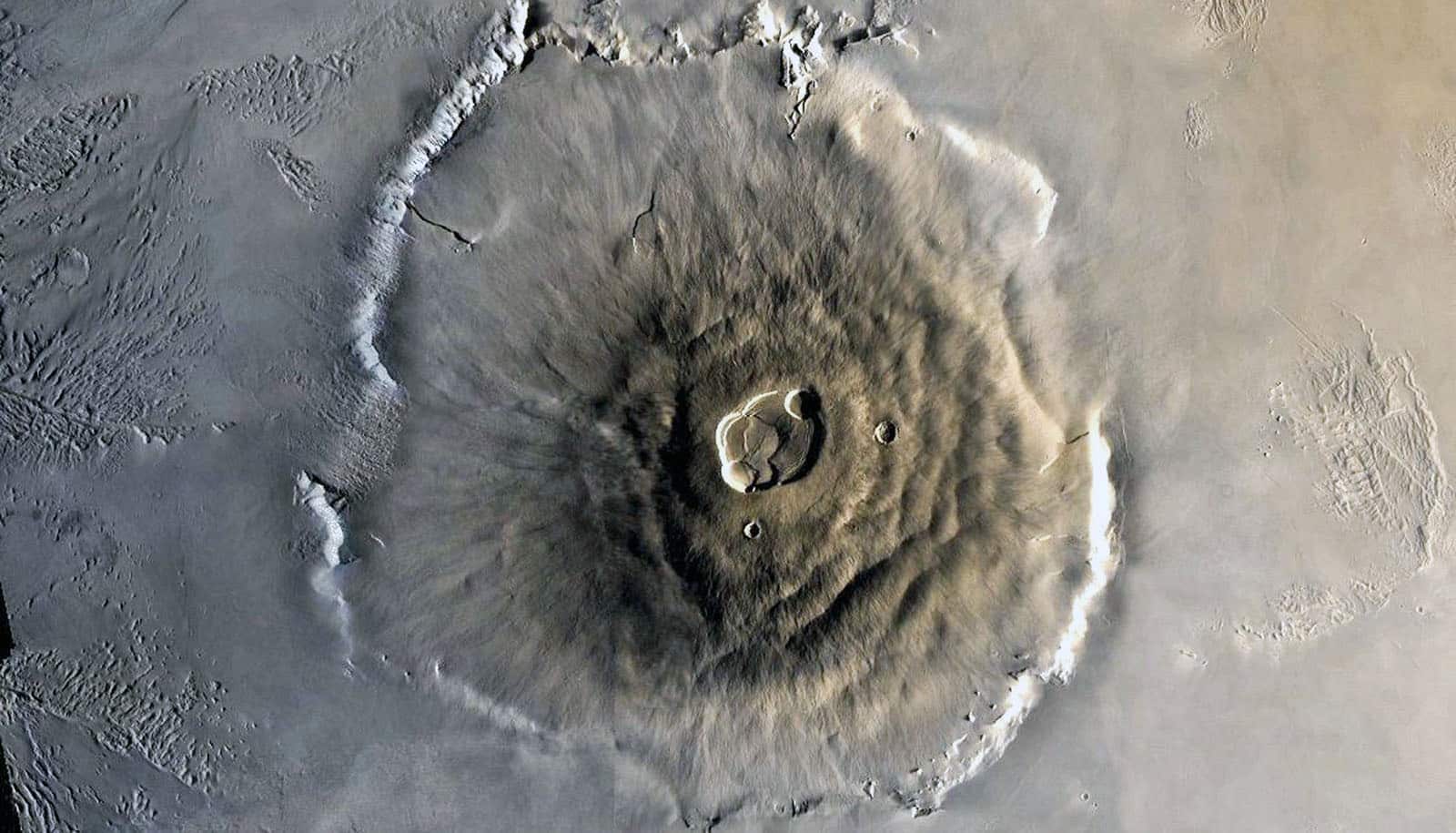

Looking at images of the vast dry, dusty Martian landscape it is difficult to imagine that about 3.6 billion years ago Mars was very much alive, at least in a geophysical sense. It spewed volcanic debris for a long enough time to give rise to Tharsis Montes region, the largest volcanic system in our solar system and the Olympus Mons—a volcano nearly three times the elevation of Mount Everest.

The quakes coming from the nearby Cerberus Fossae—named for a creature from Greek mythology known as the “hell-hound of Hades” that guards the underworld—suggest that Mars is not quite dead yet.

Here, the weight of the volcanic region is sinking and forming parallel graben (or rifts) that pull the crust of Mars apart, much like the cracks that appear on the top of a cake while its baking.

According to, Stähler it is possible that what we are seeing are the last remnants of this once active volcanic region or that the magma is right now moving eastward to the next location of eruption.

Additional coauthors are from ETH Zurich, Harvard University, Nantes Université, CNRS Paris, the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Berlin, and Caltech.

Source: ETH Zurich