Fifty years after Apollo 11 astronauts put the first seismometer on the surface of the Moon, data from NASA InSight’s seismic experiment gives researchers the chance to compare marsquakes to moon and earthquakes.

Seismologists operating the Marsquake Service literally rocked and rolled as they experienced, for the first time, two marsquakes in the quake simulator at ETH Zurich. Researchers uploaded actual data from marsquakes the SEIS seismometer detected on Martian solar day or Sol 128 and 173.

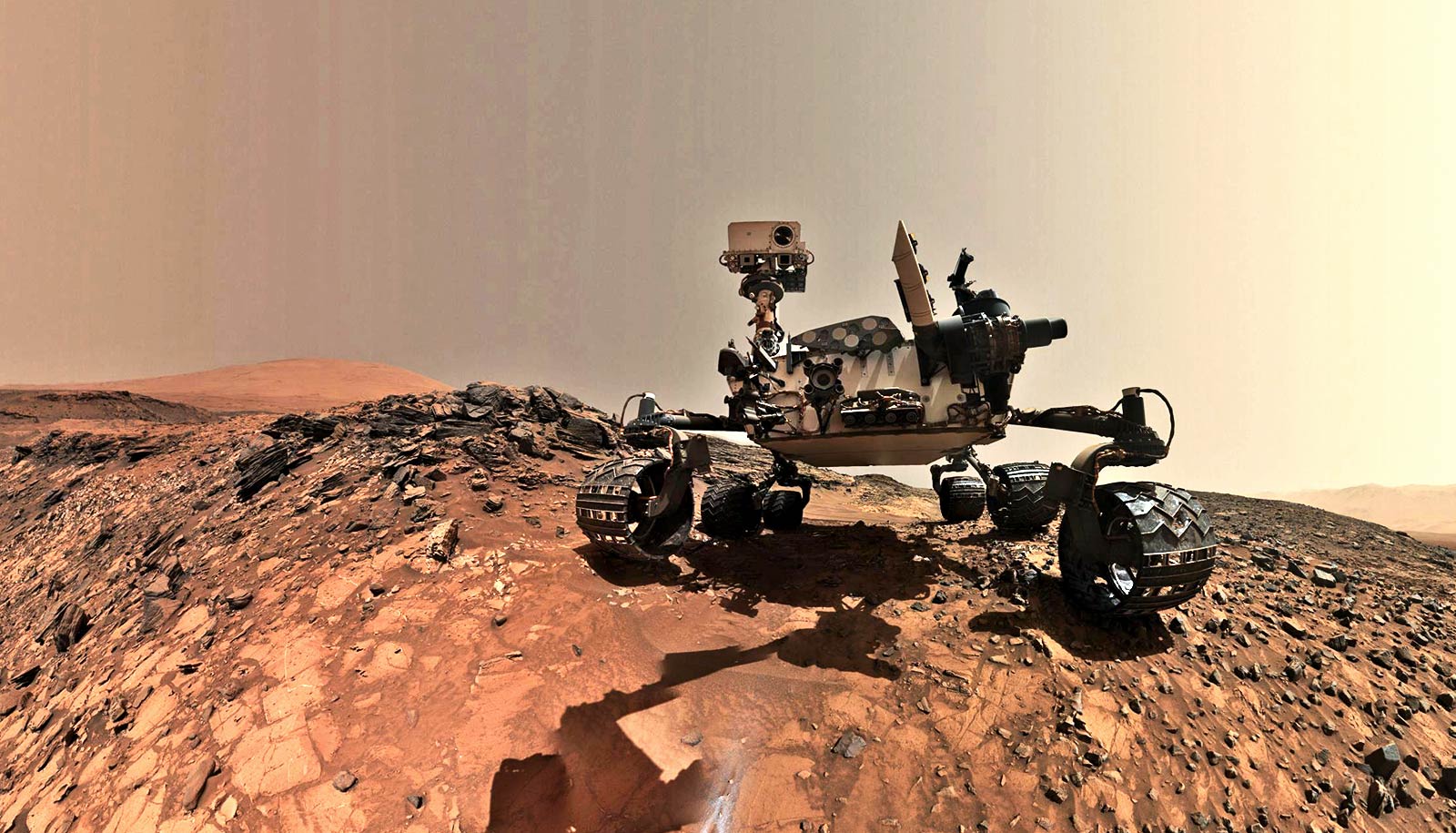

SEIS contains arguably the most sensitive seismometer ever operated, capable of detecting even the faintest seismic signals on Mars.

Researchers had to amplify the marsquake signals by a factor of 10 million in order to make the quiet and distant tremors perceptible in the quake simulator and to compare them with a similarly amplified moon and earthquake.

2 families of marsquakes

“We are currently observing two families of quakes on Mars,” says Simon Stähler. “The first quake was a high frequency event more similar to a moonquake than we expected. The second quake was a much lower frequency, and we think this may be due to the distance. The lower frequency quake likely occurred further away from the seismometer. Compared to the duration of earthquakes, both types of the marsquakes last longer.”

While seismic waves that travel through the Earth typically persist between 10s of seconds to a few minutes, moonquakes can last up to an hour or more. The extent of the seismic signal is due to distance and to differences in geological structures.

If one compares the surfaces of the Earth and the moon, it might be surprising to learn that the Earth’s crust is more homogeneous than that of the moon. Billions of years of meteorite impacts fractured the lunar crust and there is no process on the moon that “bakes” the rocks together. On the Earth, volcanism, interior heating, and plate tectonics, as well as erosion and deposition from water and wind meld broken rocks together creating a relatively unbroken and layered crust quickly erasing the traces of meteorite impacts.

“The heterogeneous lunar crust scatters seismic waves, similar to the reverberating echoes one might experience when calling out in rugged mountain terrain,” says John Clinton, who leads operations at the Marsquake Service at ETH Zurich.

The Earth’s crust and mantle, by comparison, are transparent to seismic waves—much like a wide-open space is to sound waves. While seismic sensors on Earth “hear” earthquake signals cleanly, on the Moon seismic sensors detect a plethora of echoes that distort the signal making it very hard to even identify where the signals begin.

Searching for answers with seismometers

While seismic research is still in its infancy on Mars, marsquakes appear to be somewhere in between moon and earthquakes. Researchers recognize the first seismic signals of the marsquake, but the signals that follow include more echoes than scientists expected. The duration of a marsquake signal can be approximately 10 to 20 minutes. Scientists do not yet know whether the fractured part of the Martian crust is just few kilometers deep, as it is on the moon, or if it is shallower.

Roughly, twice each day, ten seismologists analyze seismic data from Mars with the aim of detecting and characterizing marsquakes. Since there is only one seismometer on Mars, the researchers combine methods taken from the early days of seismology, when there were only a few seismometers on Earth, with modern analytic methods for locating seismic events.

Ultimately, researchers look to the seismic data to answer questions, not only about the interior geological structure of Mars, but also how early planets in the inner solar system formed more than four billion years ago.

Additional seismologists working on the Marsquake Service come from ETH Zurich, IPG Paris, ISAE Toulouse, the University of Bristol, Imperial College London, MPS Gottingen, and JPL Pasadena.

Source: ETH Zurich