The ocean’s deepest fish doesn’t look like it could survive in harsh conditions thousands of feet below the surface. Instead of giant teeth and a menacing frame, the fishes that roam in the deepest parts of the ocean are small, translucent, bereft of scales—and highly adept at living where few other organisms can.

These fish live under water pressure that can be as intense as an elephant standing on your thumb.

The Mariana snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei) that thrives at depths of up to about 8,000 meters (26,200 feet) along the Mariana Trench near Guam is named after a sailor, Herbert Swire, an officer on the HMS Challenger expedition in the late 1800s that first discovered the Mariana Trench.

“This is the deepest fish that’s been collected from the ocean floor, and we’re very excited to have an official name,” says lead author Mackenzie Gerringer, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories. “They don’t look very robust or strong for living in such an extreme environment, but they are extremely successful.”

Snailfish are found at many different depths in marine waters around the world, including off the coast of San Juan Island. In deep water, they cluster together in groups and feed on tiny crustaceans and shrimp using suction from their mouths to gulp prey. Little is known about how these fish can live under water pressure that can be as intense as an elephant standing on your thumb.

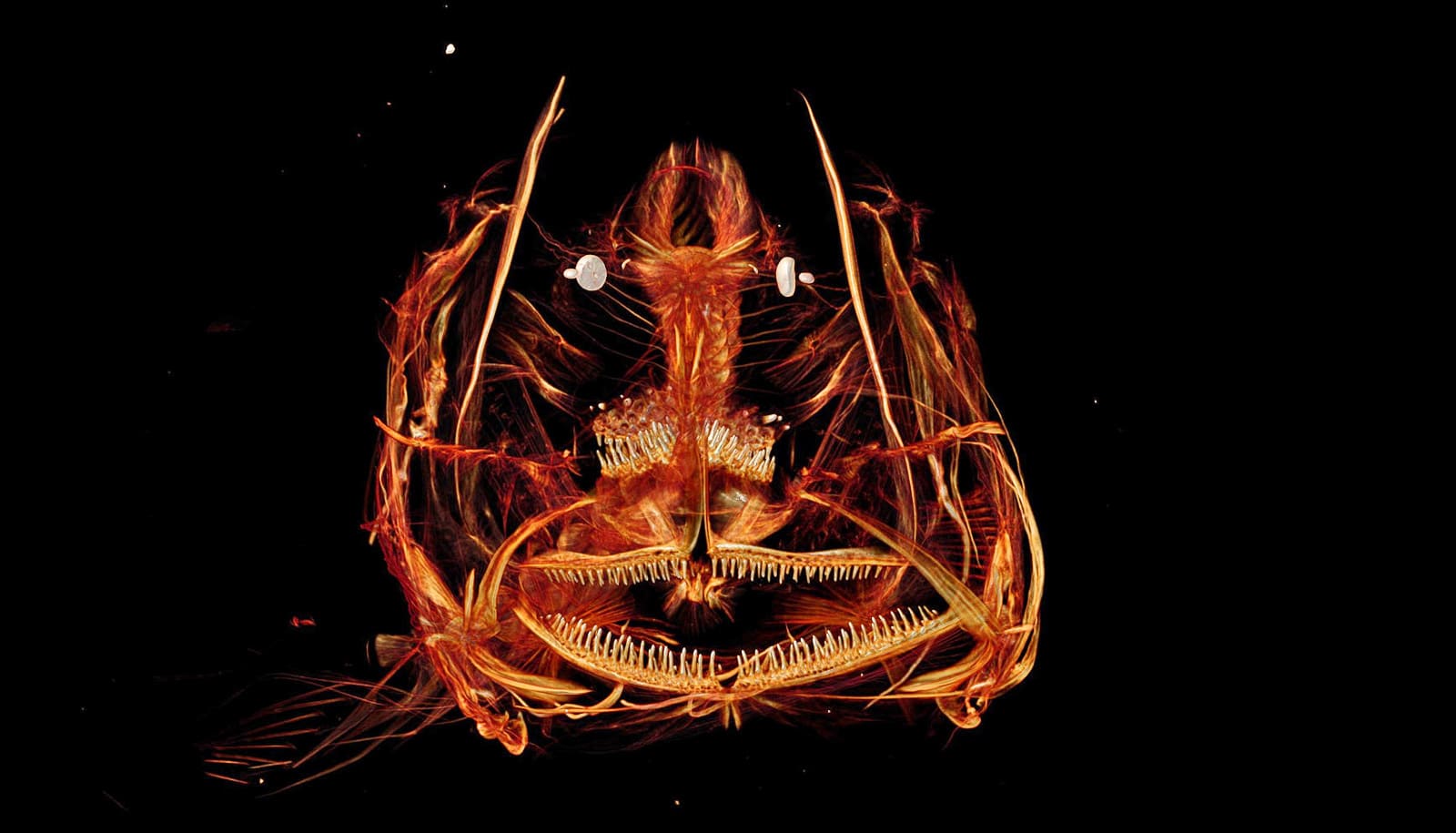

As reported in Zootaxa, the new species appears to dominate parts of the Mariana Trench, the deepest stretch of ocean in the world that is located in the western Pacific Ocean. During research trips in 2014 and 2017, scientists collected 37 specimens from depths of about 6,900 meters (22,600 feet) to 8,000 meters (26,200 feet) along the trench. DNA analysis and 3D scanning to analyze skeletal and tissue structures helped researchers determine they had found a new species.

Since then, researchers from Japan recorded footage of the fish swimming at depths of 8,178 meters (26,830 feet), the deepest sighting so far.

“Snailfishes have adapted to go deeper than other fish and can live in the deep trenches. Here they are free of predators, and the funnel shape of the trench means there’s much more food,” says coauthor Thomas Linley of Newcastle University. “There are lots of invertebrate prey and the snailfish are the top predator. They are active and look very well-fed.”

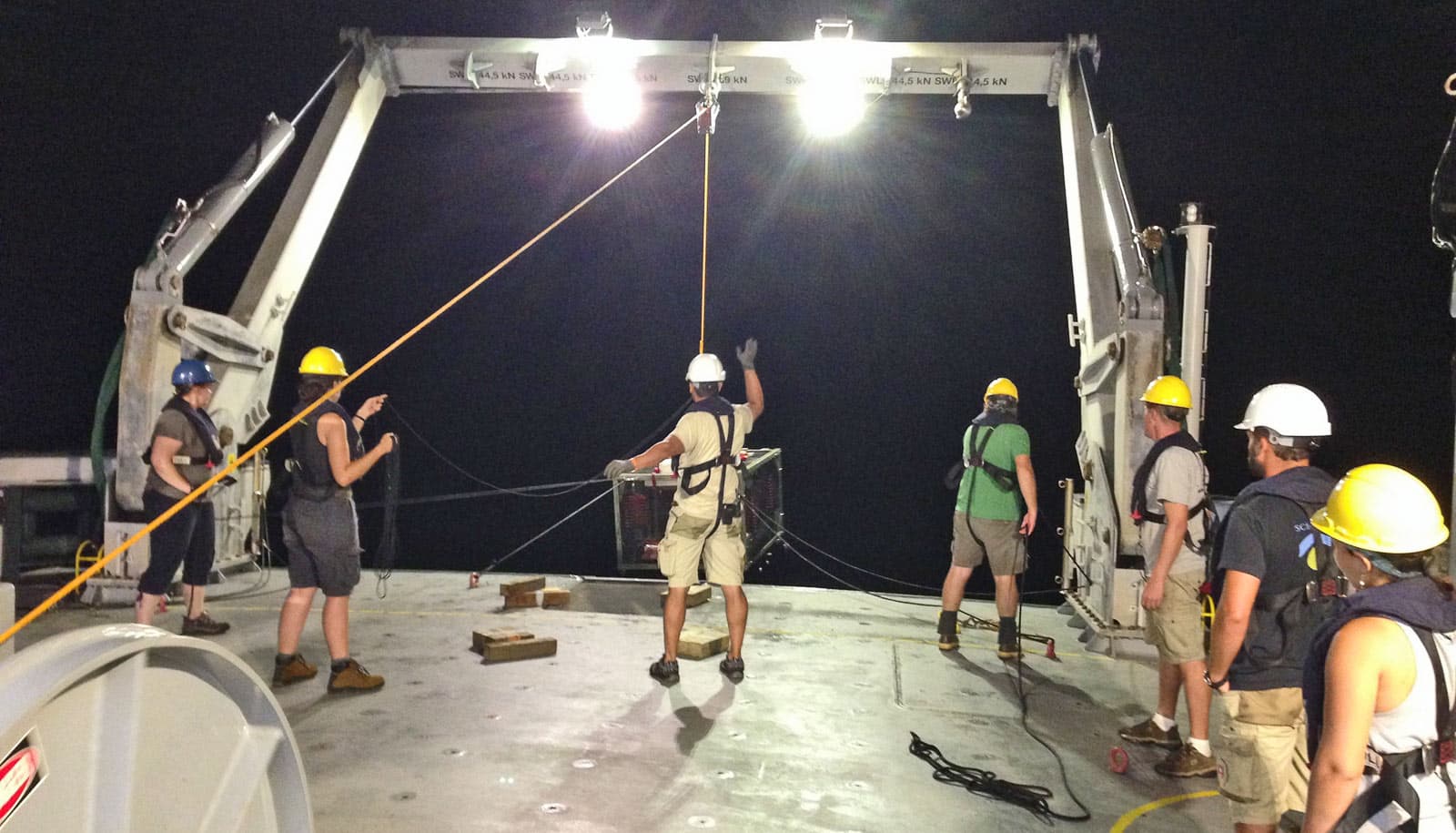

A handful of researchers have explored the Mariana Trench, but few comprehensive surveys of the trench and its inhabitants have been completed because of its depth and location, Gerringer says. These research trips, conducted while she completed her doctorate at University of Hawaii at Mānoa, involved dropping traps with cameras down to the bottom of the trench. It can take four hours for a trap to sink to the bottom.

After waiting an additional 12 to 24 hours, researchers sent an acoustic signal to the trap, which then released weights and rose to the surface with the help of flotation. That allowed scientists to catch fish specimens and take video footage of life at the bottom of the ocean.

“There are a lot of surprises waiting,” Gerringer says. “It’s amazing to see what lives there. We think of it as a harsh environment because it’s extreme for us, but there’s a whole group of organisms that are very happy down there.”

The Mariana snailfish’s location is its most distinguishing characteristic, but with the help of a CT scanner, researchers also saw a number of differences in physiology and body structure that made it clear they had found a new species.

Alan Jamieson of Newcastle University, and Erica Goetze and Jeffrey Drazen of the University of Hawaii at Mānoa are coauthors of the paper. The National Science Foundation, Schmidt Ocean Institute, and the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland funded the work.

Source: University of Washington