Events from 20,000 years ago or more still have an effect on the diversity and distribution of mammals around the world, research finds.

“Our study shows that mammal biodiversity in the tropics and subtropics today is still being shaped by ancient human events and climate changes,” says lead author John Rowan of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “In some cases, we found that ancient climate or human events were more important than their present-day counterparts in explaining present patterns of biodiversity.”

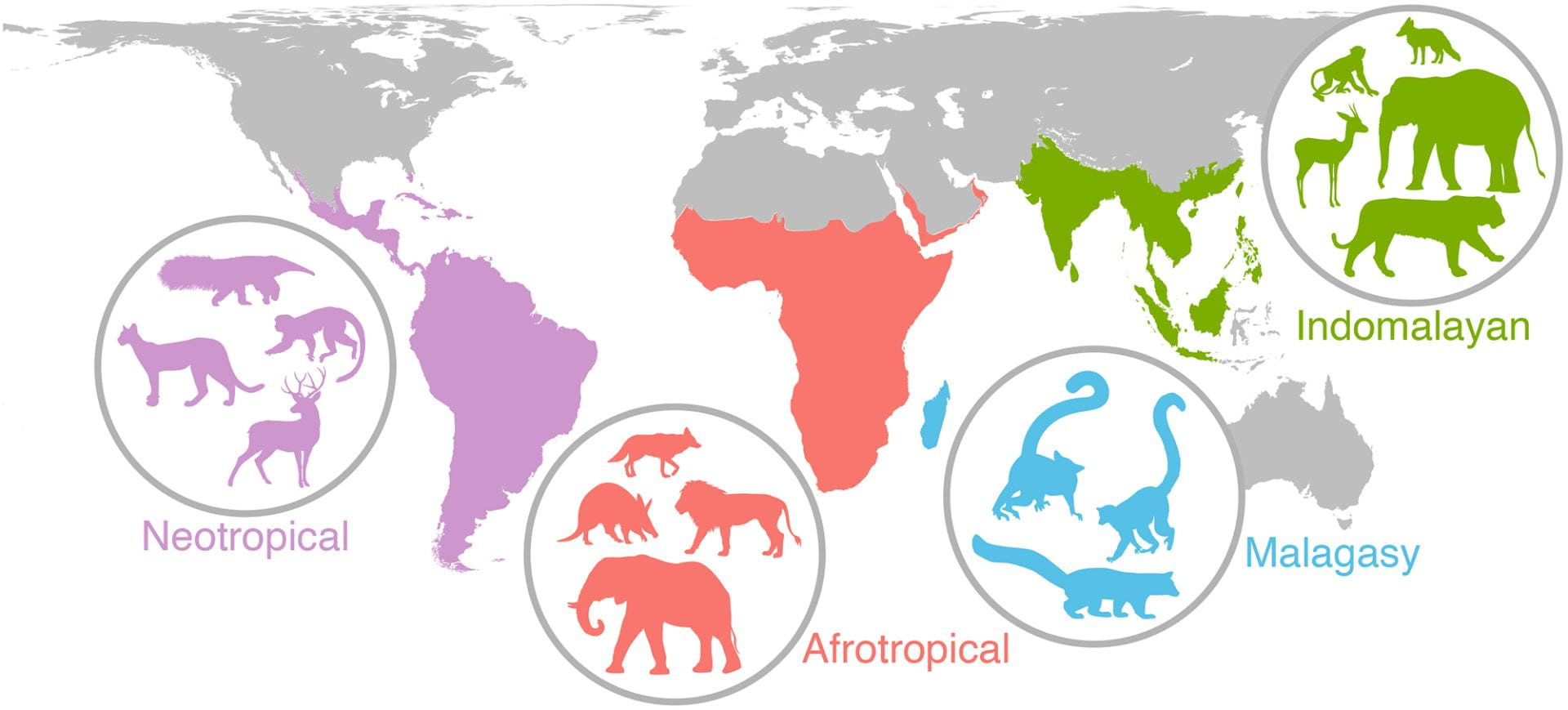

As reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers spent more than five years compiling and analyzing data about the diets, body sizes, and variety of species in 515 mammal communities—each with multiple species—in the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, Africa, and Asia. They conducted separate statistical analyses for each community to determine how well recent and ancient events—both climatic and human—could account for present-day diets, body sizes, and species variation.

Climate then and now

The study findings are especially important given the increasing questions ecologists face about how anthropogenic climate change and other human impacts will affect biodiversity this century, says coauthor Lydia Beaudrot, assistant professor of biosciences at Rice University.

“If current climate is what’s most important for where you see species, then as climate changes, we might expect species to track climate to the best of their abilities,” she says. “This study suggests things are more complex, and that we will need to take legacy effects into consideration when making predictions about how climate change will affect species distributions.”

As an ecologist, Beaudrot says she found it particularly surprising to see that historic climate does a better job than current climate of explaining the communities that are present today.

“As an ecologist, I’m typically focused on the present day, but this study demonstrates the importance of interdisciplinary research for advancing science,” she says. “When ecologists, paleoecologists, and anthropologists combine forces, we can generate and test more complex and interesting questions that generate surprising new findings.”

Mammals around the world

The study also finds that ancient human events are also still reflected in mammal biodiversity patterns. For example, most large-bodied mammals in South America went extinct when humans first appeared on the continent about 12,000 years ago.

“When you’re looking at what explain mammal communities today in the Neotropics, these historical human impacts are a better predictor than current or past climate,” she says.

Beaudrot says the reason it took so many years to complete the study was that the team had to create the database that would allow them to make comparisons across mammal communities worldwide. Most of the profiled communities are in national parks, places where conservationists have worked for years observing mammals.

“For example, the mammal communities that are most affected by climate change today are near the poles. We started in the tropics and subtropics because that’s where you find most national parks, but we want to continue adding to this, for as many communities in as many places as we can.”

The data can give scientists a clearer idea of what happened in the past and how it affected the present, but it doesn’t paint a clear picture for the future, she says.

“Predicting how species will respond to climate change is very hard,” Beaudrot says. “We already knew that, and this work suggests that it’s perhaps even more complex than we thought.”

Coauthors are from the University of California, Riverside; ASU; and UMass Amherst. The National Science Foundation supported the work.

Source: Rice University