Liquid smoke, the popular food additive, could benefit plants, research finds.

When the researchers added liquid smoke to the soil where a plant was growing, they found it could enhance the plant’s natural defenses and increase its ability to resist pests and diseases, says Richard Ferrieri, a research professor in the chemistry department and investigator at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR).

Liquid smoke, created by condensing smoke from burning wood, was used to provide a simulation—in a laboratory setting—of the smoky conditions a wildfire could create.

“Plants can’t run away when they are trying to defend themselves from an active threat,” says Ferrieri, who is also a member of the Interdisciplinary Plant Group at the university. “Therefore, it takes a lot of energy for a plant to dedicate precious resources it would normally dedicate to its growth to now defend itself. Much like the human body, a key to plant health lies in how well its vascular system can function under stress and move precious resources to the different growing parts.”

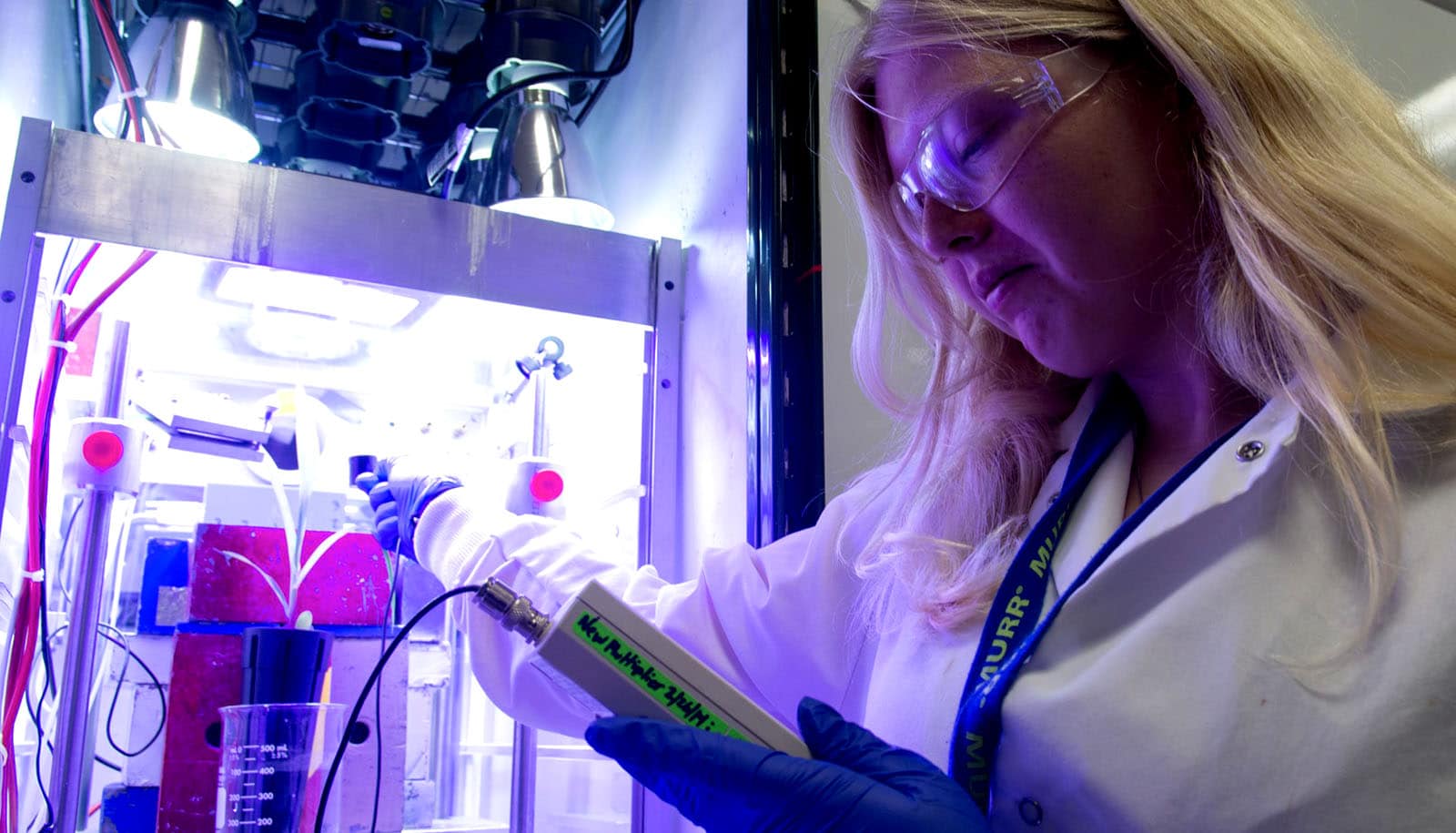

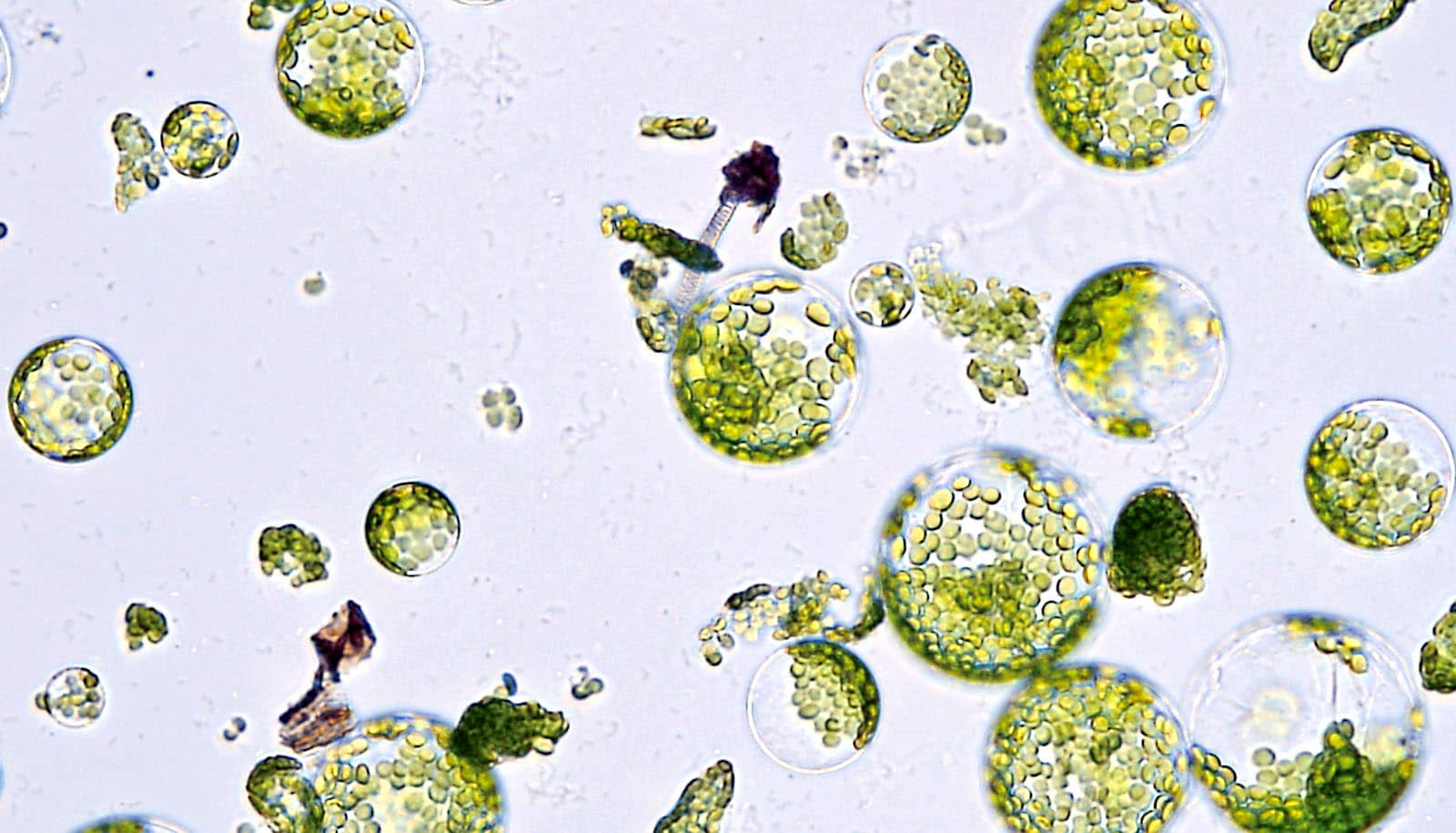

In this study, scientists used the radioisotope carbon-11—created by a cyclotron at MURR—to help them trace how smoke affects a sunflower’s vascular system, or the system that transports carbon, water, and micronutrients throughout the plant. Ferrieri says they found that sunflowers grown in soil treated with liquid smoke had larger, thicker, and greener leaves and appeared less prone to pests and disease.

“Plants harness the energy of the sun, fix carbon dioxide, and make sugars that are transported throughout the plant using their vascular system,” Ferrieri says. “By feeding carbon dioxide gas containing carbon-11 to a common domesticated variety of sunflower, we were able to create a physical map of where the sugars go using radiographic imaging. This allowed us to evaluate the effects of smoke on vascular transport.”

The Plant Radiotracer Laboratory at MURR largely includes an array of equipment that was moved to the University of Missouri from the US Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory after more than 30 years. Inside the lab, Ferrieri has been using carbon-11, along with other radioisotopes produced at MURR, to study how plants respond to stresses imposed by their environment.

In the future, Ferrieri wants to expand upon this research by testing agriculture crops, such as soybeans. He says soybeans could be a natural extension of their existing research because they share a similar type of vascular system with sunflowers, and they are also susceptible to developing various diseases.

“Leaf blight is a soybean disease caused by a certain type of bacteria,” Ferrieri says. “These bacteria can winter over when crops are tilled back into the soil leaving next season’s crops susceptible to the same blight. What we want to do is determine whether a treatment of the soil with liquid smoke could potentially protect the plants from this blight and other pathogens.”

Ferrieri hopes his lab’s work could help provide a possible solution for the issue of global food security by providing a natural alternative to the use of pesticides to help farmers increase the resilience of their crops against developing various diseases. Ultimately, he says this approach could potentially help increase the amount a farmer is able to grow of a particular crop.

The study appears in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Ferrieri acknowledges the team of undergraduate students who contributed to the research.

Funding came in part from the Department of Energy and from internal funds through the University of Missouri. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri