Genes in fruit flies may explain differences in the learning speed of flies, researchers report.

Many of those genes in fruit flies are similar to those found in people. The research in fruit flies could one day provide new avenues to discover additional genes that contribute to a person’s ability to learn and remember.

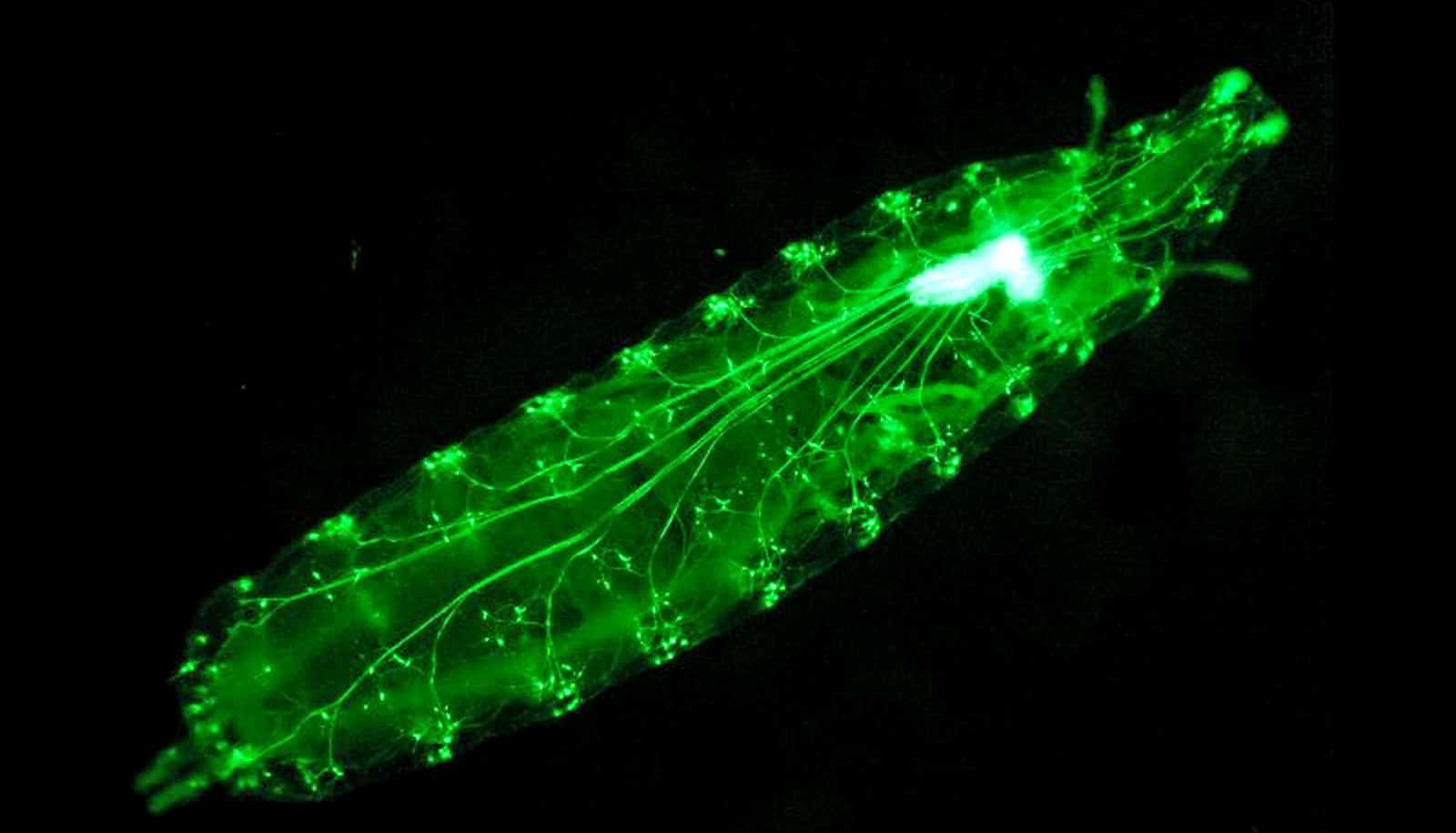

Past experiments studying how fruit flies’ ability to learn and remember have involved “turning off” a single gene and watching the response. In this study, the scientists took a different approach by placing fruit flies in a box equipped with heating elements.

When the heat was turned on, the flies—uncomfortable in heat—moved to the far side of the box where it was cooler. A fly’s ability to avoid the heat measured how well it learned, and a fly’s ability to avoid the hotter side of the box, even when the heat was off, measured its capacity to remember.

“Some flies learn fast and remember to stay away from the heat whereas some flies take longer to figure it out,” says Patricka Williams-Simon, a doctoral fellow in biological sciences at the University of Missouri.

“We repeated the experiment with over 40,000 individual fruit flies from over 700 different genes to establish variation in performance. Then, we focused on the high and the low learning and memory performers.”

The scientists then took these results and applied genetic sequencing technology to determine if specific genes were responsible for the observed changes in a fly’s behavior. They found nine genes that show a change between high and low performing files when it comes to learning and memory.

“All of these genes are previously known to affect the nervous system or the brain in some way, but none of them had previously been implicated in learning and memory,” says Elizabeth King, an assistant professor of biological sciences. “Therefore, they represent novel areas to further investigate these behavioral traits.”

While the study is considered basic research, Williams-Simon says their findings are important.

“The better we can understand these traits in fruit flies, the more we can develop targeted studies in humans,” Williams-Simon says.

The study appears in Genes, Brain, and Behavior. Additional coauthors are from the University of Missouri and the University of Iowa. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of coauthor Troy Zars to this study, who passed away in 2018.

Funding came from the National Science Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the National Institute of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri