New maps show the effect of past and future hydropower dams on global fish habitats, researchers report.

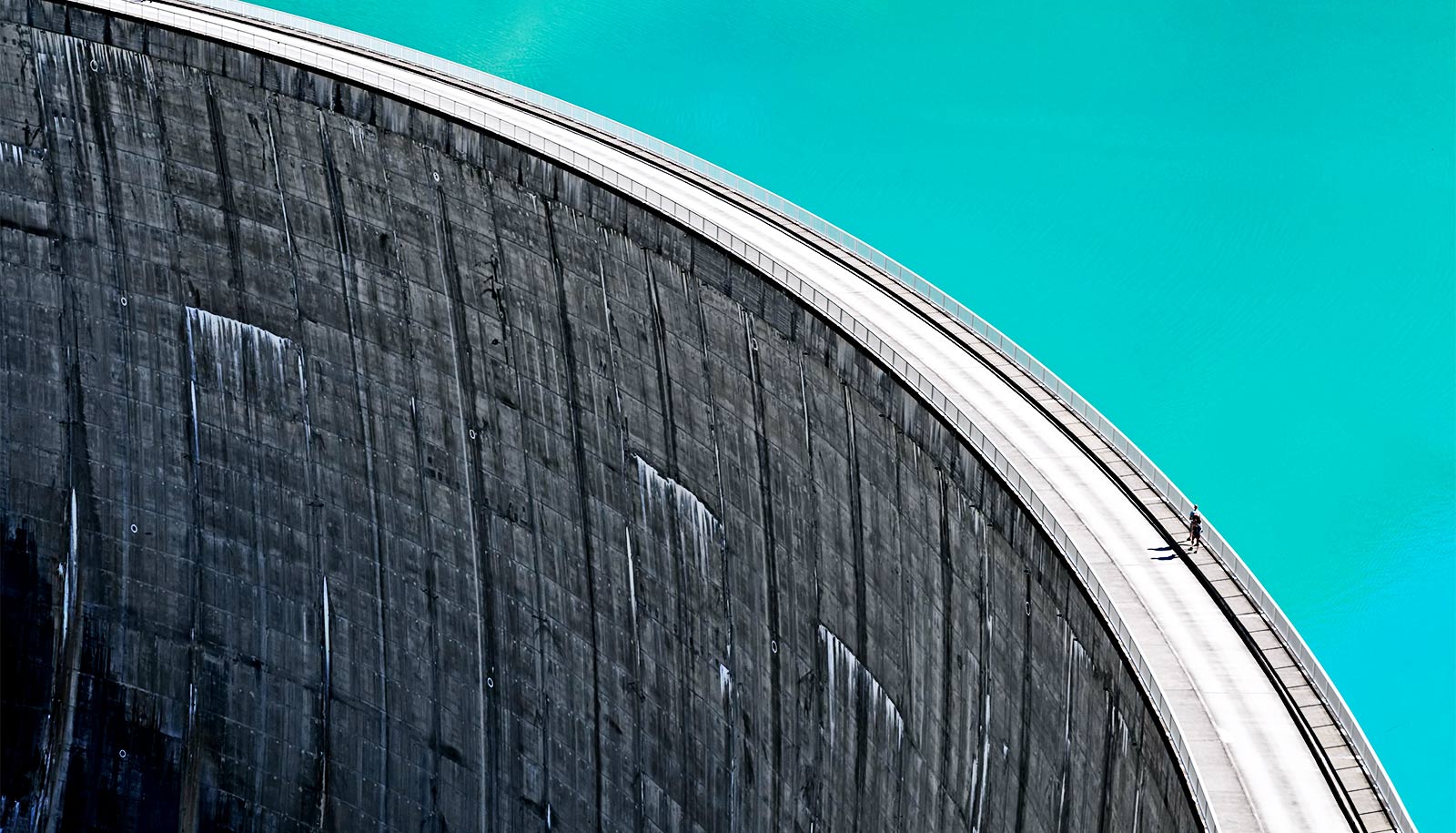

Rivers and other ecosystems that provide essential habitats to freshwater fish are under increasing pressure from global hydropower development. While dams can provide flood protection, energy supply, and water security, they also pose a significant threat to freshwater species.

Dams block fish from moving along their natural pathways between feeding and spawning grounds, causing interruptions in their life cycles that limit their abilities to reproduce.

As hydropower development continues along river basins around the world, scientists are concerned about the unknown impacts to the diverse species found in freshwater habitats—many of which are critical sources of food and livelihood for humans.

“These dams pose a real danger to the survival of species and associated human livelihoods.”

“Because fisheries based on migratory species support tens of millions of people, understanding where hydropower development could negatively impact river basin connectivity—and therefore fish—is an important step in identifying solutions that deliver needed electricity while minimizing the loss of essential natural resources,” says Jeff Opperman, global lead freshwater scientist for World Wildlife Fund.

Without detailed information about where exactly freshwater species feed and spawn, it has been difficult for planners to make more sustainable decisions around hydropower and river basin development.

A major threat to fish habitats

“We’ve known that future development will impact fish species, but we didn’t have the detailed information about some of the places with the highest development pressures—like the Amazon, the Mekong, and the Congo—until now,” says second author Rafael Schmitt, a researcher at the Stanford University Natural Capital Project.

“This dataset will help decision-makers better understand impacts of land and infrastructure development on aquatic biodiversity, so they can make choices that protect it.”

The researchers used detailed spatial data for 10,000 fish species to measure impacts of dams on their habitats. They evaluated around 40,000 existing and 3,700 planned hydropower dams to create high resolution global maps.

“These dams pose a real danger to the survival of species and associated human livelihoods,” says Schmitt. “Salmonids in North America were mostly wiped out by dams, and with them the livelihoods of people depending on their annual migration. Now, similar impacts become evident in other geographies.

“Recently, we’ve seen how dams on the Yangtze contributed to the extinction of the Chinese paddlefish, a source of food and cultural reverence for communities along the river. If we aren’t more strategic about where and how we develop future hydropower, we can expect to see more and more examples like this one.”

Strategically placing new hydropower dams

The study shows the highest numbers of fragmented habitats from current hydropower are found in the United States, Europe, South Africa, India, and China. In developing countries, though, the impacts of planned hydropower development are disproportionally high.

“For example, we see that the completion of only one dam close to the outlet of Purari River in Papua New Guinea will decrease habitat connectivity by about 80% on average for freshwater fish in the region,” says lead author Valerio Barbarossa, an environmental researcher at Radboud University.

“With these maps, we have a global picture of where fish species are already impacted by dams and where local conservation efforts should be fostered,” says Barbarossa.

The researchers hope that their results will help guide strategic decision-making around hydropower planning.

“Evaluating impacts of dams is only the first step,” says Schmitt. “These data can be used to highlight the additional benefits of thoughtful, strategic river basin development to drive conservation and restoration efforts in local areas and at global scales.”

The research appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source: Stanford University