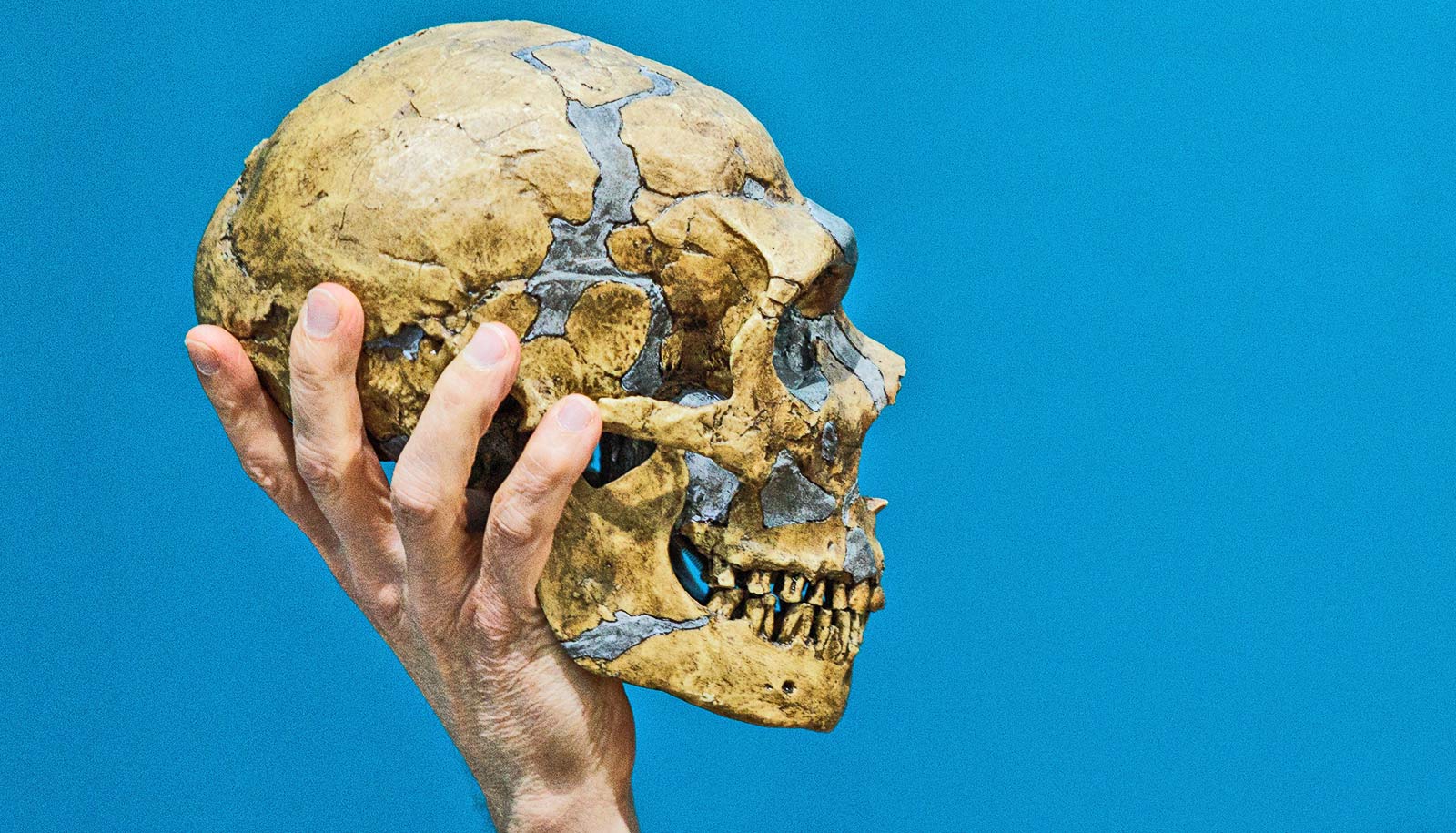

Scientists have determined that bones from the foot of an ancient human ancestor discovered in Ethiopia belong to a hominin species that lived at the same time as the famous hominin species Lucy.

The foot bones were discovered in 2009 by paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie of Arizona State University, who now leads a research team that has determined that the 3.4-million-year-old fossils belong to the species Australopithecus deyiremeda. The finding also confirms that Australopithecus deyiremeda existed in the same time and place as Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy’s species.

The results, funded by the National Science Foundation and the W.M. Keck Foundation, are published in the journal Nature.

University of Michigan geochemist Naomi Levin was part of the team. Her work shows that these two species had different diets, reflecting different adaptations to their environment. She says that the way these hominins adapted—or didn’t—to their climate can teach us lessons for how we can adapt to our own.

These hominins were living at a time when Earth didn’t have permanent ice in the Arctic but when carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were just a little less than today.

“Studying the environments of human ancestors gives us a peek into what life was like during a time of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations and insights into how some of them might have gained a competitive edge over others,” says Levin, a professor in the University of Michigan earth and environmental sciences department.

“The last time carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere were as high as today, the genus Homo hadn’t even appeared yet. Humans evolved during a time when carbon dioxide levels were decreasing, and they were adapting to changing environments. These fossils help us understand what life was like millions of years ago. If we don’t understand how humans have interacted with the environment going back in time, we have no perspective on today.”

In 2009, scientists found eight bones from the foot of an ancient human ancestor within layers of million-year-old sediment in the Afar Rift in Ethiopia. The team found the fossil, called the Burtele Foot, at the Woranso-Mille paleontological site.

“When we found the foot in 2009 and announced it in 2012, we knew that it was different from Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, which is widely known from that time,” Haile-Selassie says.

“However, it is not common practice in our field to name a species based on postcranial elements—meaning elements below the neck—so we were hoping that we would find something above the neck in clear association with the foot.”

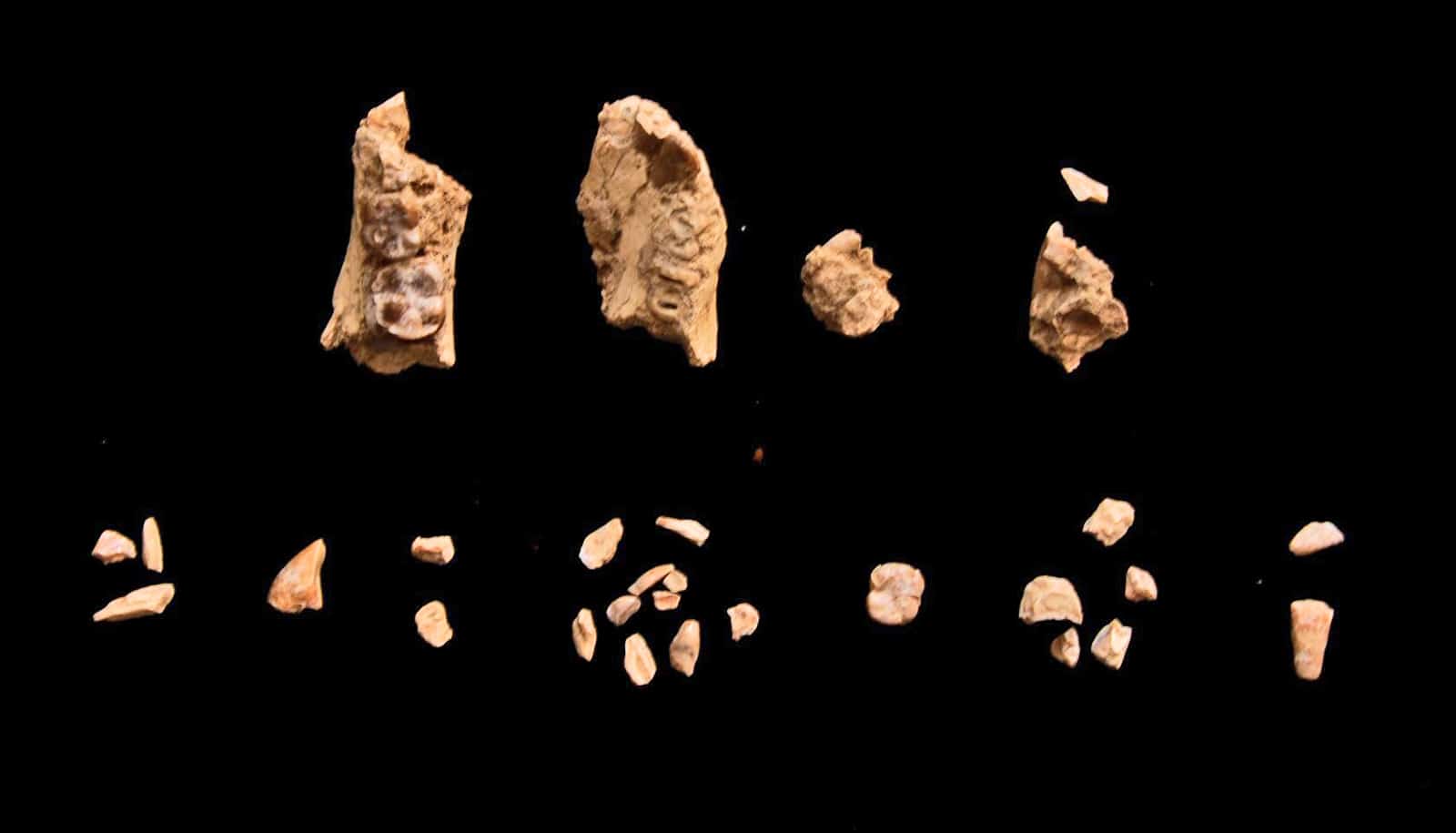

When the Burtele Foot was announced, some teeth were already found from the same area, but the scientists were not convinced the teeth were from the same level of sediments. Then, in 2015, the team announced a new species, Australopithecus deyiremeda, from the same area but still did not include the foot into this species even though some of the specimens were found very close to the foot.

Over the past 10 years of going back into the field and continuing to find more fossils, researchers now have specimens that they can confidently associate with the Burtele Foot and with the species A. deyiremeda.

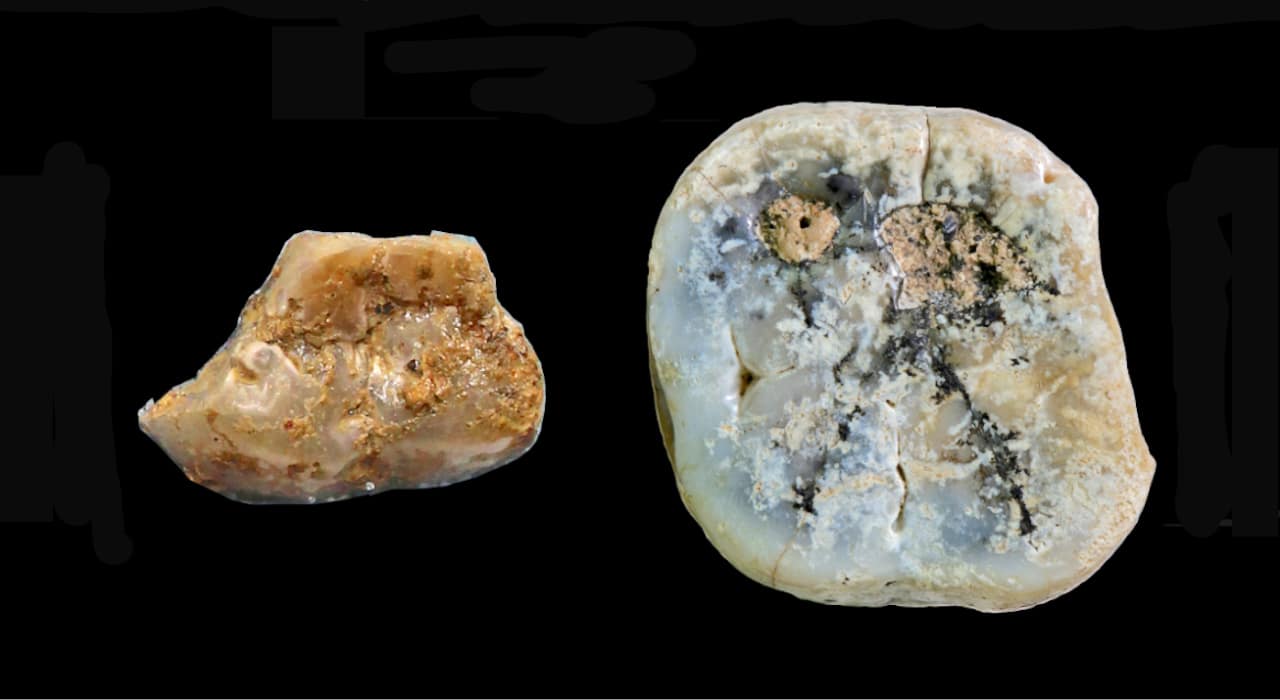

To get insight into the diet of A. deyiremeda, Levin sampled eight of the 25 teeth found at the Burtele areas for isotope analysis. The process involves using very tiny tools like today’s dentists use.

She found that the newer hominin species was eating foods from trees and shrubs. Lucy’s species, however, was able to eat a broader range of foods, sourced from trees and shrubs as well as tropical grasses and sedges.

“Lucy’s species was figuring out how to take advantage of additional foods and they were walking in a different way. My data shows that A. deyiremeda had a more restricted diet than A. afarensis,” Levin says.

“They were in the same environment, but doing different things. This is the way that organisms survive, and the way we are going to survive, is that we have to adapt.”

The assignment of the Burtele Foot to a species is just part of the story. The site of Woranso-Mille is significant because it is the only site where scientists have clear evidence showing two related hominin species coexisted at the same time in the same area, Haile-Selassie says.

The Burtele Foot, belonging to A. deyiremeda, is more primitive than the feet of Lucy’s species, A. afarensis. The Burtele Foot retained an opposable big toe which is important for climbing and the toes were longer and more flexible, also suitable for climbing. But when A. deyiremeda walked on two legs, it most likely pushed off on its second digit rather than its big toe like we, modern humans, do today.

“So what that means is that bipedality—walking on two legs—in these early human ancestors came in various forms,” Haile-Selassie says.

“The whole idea of finding specimens like the Burtele Foot tells you that there were many ways of walking on two legs when on the ground—there was not just one way until later.”

Along with the 25 teeth found at Burtele, scientists also found the jaw of a juvenile that clearly belonged to A. deyiremeda. This jaw had a full set of baby teeth already in position, but also had a lot of adult teeth developing deep down within the bony mandible, according to the researchers.

The juvenile jaw indicates that the two species were remarkably similar in the manner in which they grew up. However, the geochemistry of the teeth and the anatomy of the foot shows that they were eating different things and walking in different ways, Levin says.

Knowing how these ancient ancestors moved and what they ate provides scientists with new knowledge about how species coexisted at the same time. Together, the research allows scientists to examine how organisms adapt to survive in their environments—something humans will have to do in a changing climate.

“We actually have a unique situation, which is that we can control what the future looks like, and that means how much carbon we put in the atmosphere,” Levin says.

“But we’re also going to have to adapt—we’re going to have to adapt to systems that rely less on fossil fuels and how to figure out how to live in a warmer world. This is how our species is going to survive.”

Source: University of Michigan