Researchers have introduced new methods that reveal which regions of the brain were active throughout the day with single-cell resolution.

Using mouse models, the researchers developed an experimental protocol and a computational analysis to follow which neurons and networks within the brain were active at different times.

Published in the journal PLOS Biology, the study provides new insights into brain signaling during sleep and wakefulness, which hints at the bigger questions and goals that motivated the work.

“We undertook this difficult study to understand fatigue,” says senior author Daniel Forger, a University of Michigan professor of mathematics.

“We’re seeing profound changes in the brain over the course of the day as we stay awake and they seem to be corrected as we go to sleep.”

What the team found and how they found it could help lead to new ways to objectively assess fatigue in humans. These could in turn be used to help ensure people with high-stakes responsibilities, such as pilots and surgeons, are adequately rested before starting a flight or an operation.

“We’re actually terrible judges of our own fatigue. It’s based on our subjective tiredness,” Forger says. “Our hope is that we can develop ‘signatures’ that will tell us if people are particularly fatigued, and whether they can do their jobs safely.”

While researchers at the University of Michigan created the mathematical and computational workflows to analyze and interpret data, collaborators in Japan and Switzerland were developing a powerful new experimental approach.

They leveraged a cutting-edge form of imaging called light sheet microscopy that enabled them to generate 3D images of mouse brains. They also introduced a genetic tagging method that resulted in active neurons glowing under the microscope, allowing the researchers to see which cells were active across the brain and when.

“We know from studies over the last 20 or 30 years, how to decipher how one aspect—a gene or a type of neuron, for instance—can contribute to behavior,” says Konstantinos Kompotis, a study coauthor and senior scientist at the Human Sleep Psychopharmacology Laboratory at the University of Zurich.

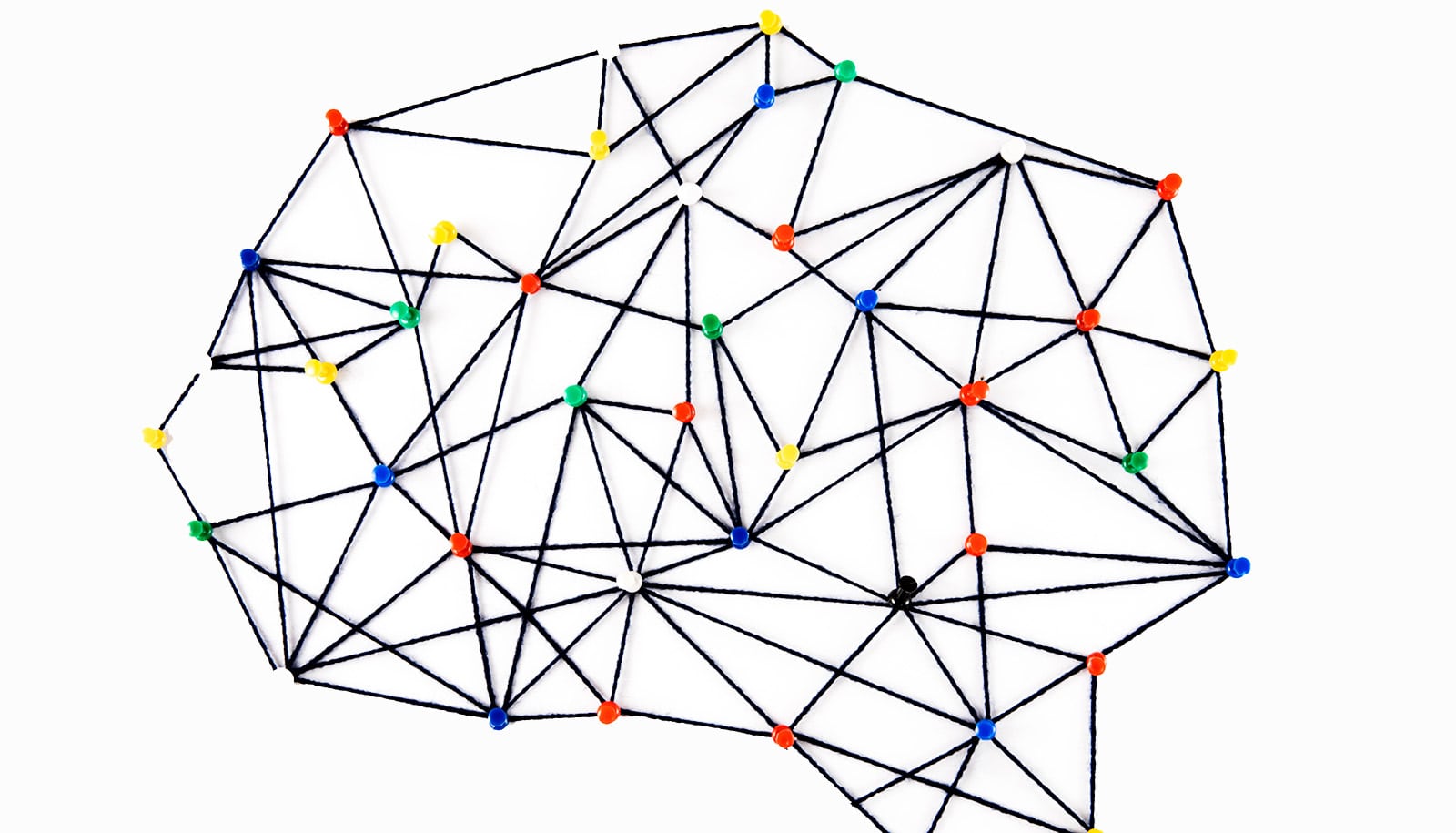

“But we also know that whatever governs our behavior, it’s not just one gene or one neuron or one structure within the brain. It’s everything and how it connects and interacts at a given time.”

The Human Frontier Science Program brought together teams across three countries to investigate those connections and interactions more deeply. That included the UM team, the Zurich team, and a Japanese team, led by Hiroki Ueda of the Laboratory for Synthetic Biology at the RIKEN Center for Biosystems and Dynamics Research.

Working together, the team saw that, generally speaking, as mice wake up, activity starts in inner, or subcortical, layers of the brain. As the mice progressed throughout their day—or night, rather (they are nocturnal)—hubs of activity moved to the cortex at the brain’s surface.

“The brain doesn’t just change how active it is throughout the day or during a specific behavior,” Kompotis says. “It actually reorganizes which networks or communicating regions are in charge, much like a city’s roads serve different traffic networks at different times.”

This finding, and how it was made, provides foundational steps toward identifying signatures of fatigue and more, Forger says. For example, he also suspects that exploring this general pattern further could yield ties to mental health.

“This study doesn’t touch on that,” Forger says. “But I do think the activity we saw in different regions is going to be important for understanding certain psychiatric disorders.”

Furthermore, Kompotis has already started working with industrial partners to use the team’s experimental techniques to probe how different therapeutics and drug candidates affect brain activity.

Although the new experimental techniques are not applicable to humans, researchers can translate certain findings from mouse models to human physiology, Forger says. And the computational approaches developed for this study are generalizable, says coauthor Guanhua Sun. Sun worked on this project as a doctoral student at UM and is now a Courant Lecturer at New York University.

“The mathematics behind this problem are actually quite simple,” Sun says.

That simple math enabled the team to combine their new data with existing data sets on mouse brains. The challenge, Sun says, was making sure that how they combined that data was done in a manner that was consistent with biology and neurology. So long as that standard is upheld, the team’s computational approach could be applied to human data gleaned from EEG, PET, and MRI scans, he says.

“The way we detect human brain activity is more coarse-grained than what we see in our study,” Sun says. “But the method we introduced in this paper can be modified in a way that applies to that human data. You could also adapt it for other animal models, for example, that are being used to study Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. I would say it’s quite transferable.”

On a more personal note, the team dedicated this study to Steven Brown, a colleague who died in a plane crash during the project.

“Steve was a perfect collaborator,” Forger says.

Brown is a senior coauthor on the new study and was a professor and section leader for chronobiology and sleep research at the University of Zurich.

“We learned how important one person can be in scientific research, be it in brainstorming or in bridging ideas and concepts. Steve was a core element of this collaboration,” Kompotis says. “It is yet another reason for us to be very proud of this story.”

The study was supported by federal funding from the US National Science Foundation and the US Army Research Office. It also received funding from the Human Frontier Science Program, or HFSP, that enables pioneering work in the life sciences through international collaboration, which was key to this study.

Source: University of Michigan