Homo sapiens were able to thrive because they could generalize across different kinds of environments, but then also rapidly specialize upon encountering specifically challenging environments, say researchers.

They call this new ecological role the “general specialist.”

The Homo sapiens that migrated out of Africa about 80,000 years ago settled with relative ease into habitats as wide-ranging as sultry rainforests and high, wintry mountain ranges.

Traditionally, paleoarchaeologists have argued that our species succeeded in such different environments—and survived instead of going extinct—because we underwent a dramatic cognitive change that involved, among other advancements, a greater capacity for symbolism.

“What was remarkable is how successful we became in so many different habitats as early as we did.”

“It wasn’t just that we were a generalist inhabiting a series of diverse environments. Once we got into a particularly difficult area, we were able to successfully colonize that area by becoming much more specialist in that we focused on resources and their configurations specific to that environment,” says Brian Stewart, assistant professor in the anthropology department at the University of Michigan and coauthor of the paper in Nature Human Behaviour.

“Homo sapiens displayed an ability to live in every single habitable biome, including forgiving places like the Mediterranean but also the high Arctic and the high Andes. To tack between diametrically opposed subsistence and settlement strategies with ease typifies our species and gave us a competitive advantage over other species of human.”

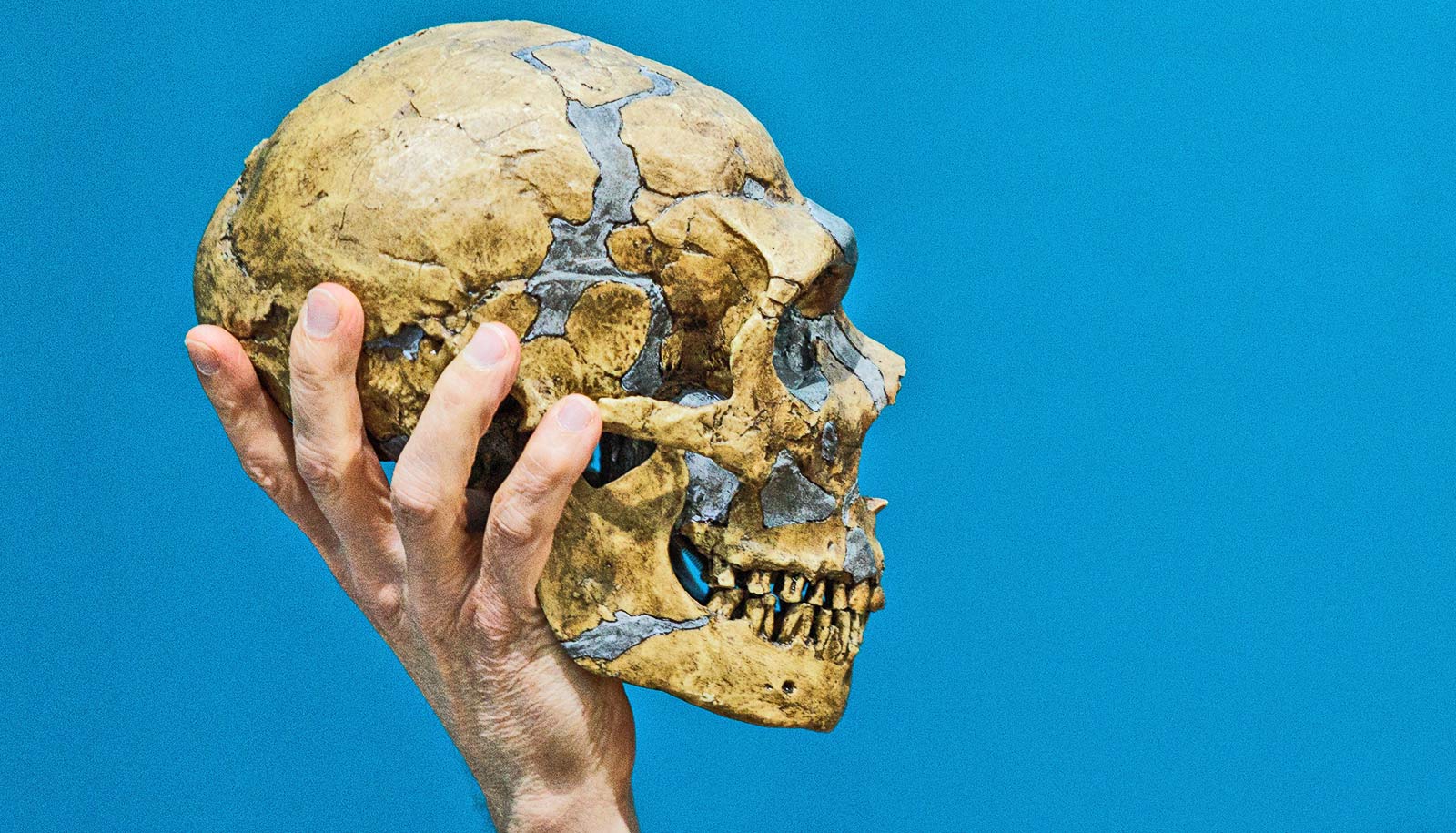

Stewart and lead author Patrick Roberts of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany examined evidence for the proliferation of members of the genus Homo across parts of the world. Homo erectus colonized areas in western Asia, China, Indonesia, and Europe 1-2 million years ago but eventually the species dwindled and became extinct. Neanderthals spread to mid-latitude Eurasia between 250,000 and 400,000 years ago, but again, their species became extinct.

“Additionally, we now have strong evidence that behavioral traits we used to think of as exclusive to Homo sapiens, including complex language, symbolic use of material culture, and so on, were being exhibited by other human species, especially Neanderthals,” Stewart says.

This means it is likely most major cognitive advances had already occurred with the last common ancestor we shared with other species such as Neanderthals—the ancestor called Homo heidelbergensis, according to Stewart.

Late in the Pleistocene, between 12,000 and 100,000 years ago, the species Homo sapiens proliferated across the world. There’s evidence of our species in paleoarctic settings and high-elevation environments, as well as in tropical rainforests across Asia, the Americas, and Melanesia, a region near Australia that includes Fiji, Papua New Guinea, West New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands.

Roberts and Stewart say Homo sapiens’ ability to succeed in such a wide variety of habitats reflects the abilities of a generalist specialist.

“A traditional ecological dichotomy exists between ‘generalists,’ who can make use of a variety of different resources and inhabit a variety of environmental conditions, and ‘specialists,’ who have a limited diet and narrow environmental tolerance,” Roberts says.

“However, Homo sapiens demonstrate evidence for ‘specialist’ populations, such as mountain rainforest foragers or paleoarctic mammoth hunters, existing within what is traditionally defined as a ‘generalist’ species.”

Drying climate sparked human migration from Africa

Homo sapiens may have been able to develop this particular ability by cooperating with other Homo sapiens to whom they weren’t related, Stewart says. These non-kin groups would have shared food, communicated over longer distances, and had ritual relationships that allowed populations to adapt to local environments quickly.

“Having a vast trove of cultural information available to do things like make clothing, build the shelters you need, find a spouse—all the things you need for life beyond simply the diet—was critical for the survival of groups in new regions,” Stewart says. “What was remarkable is how successful we became in so many different habitats as early as we did.”

Next, the researchers hope to examine the roots of this success, which lay within Africa.

“My research involves unearthing the African roots of this kind of ecological plasticity,” Stewart says. “Why, where, and when in Africa did this happen? It’s a trickier and thornier set of questions.”

Source: University of Michigan