People who receive emergency financial assistance are less likely to become homeless, a new study shows.

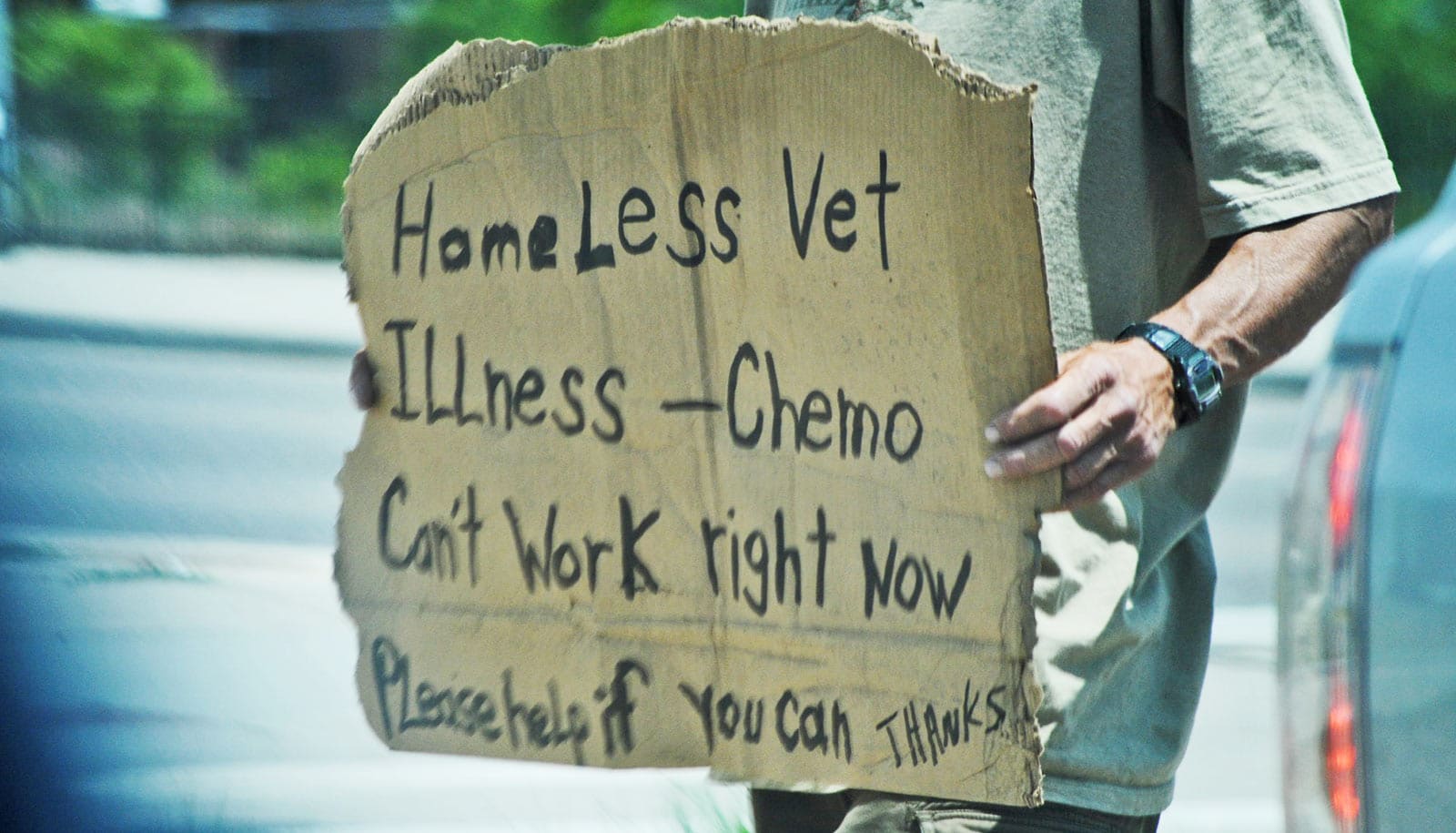

Homelessness has become an increasingly worrisome crisis in our nation over the past several years. The issue has reached such proportions in California, for example, that mayors of several major cities have declared a state of emergency on homelessness.

In response, leaders in California have invested billions in homelessness programs, including some that target prevention.

Prevention efforts, however, have led to questions—even from organizations committed to addressing homelessness—as to whether such programs are effective, due to the difficulty of targeting assistance to those with the greatest risk of becoming homeless.

To test the impact of providing financial assistance to those susceptible to losing their housing, researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of emergency financial assistance (EFA) on families receiving support through the Santa Clara County Homelessness Prevention System, which is co-led by Destination: Home, a nonprofit organization dedicated to ending homelessness in Silicon Valley.

“Every person who ends up homeless is a little different from the next…”

David Phillips, a research professor in the Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities (LEO) within the economics department at the University of Notre Dame, and James Sullivan, a professor of economics and co-founder of LEO, found that people offered EFA were 81% less likely to become homeless within six months of enrollment and 73% less likely within 12 months.

The study appears in the Review of Economics and Statistics.

The study evaluated individuals and families at imminent risk of being evicted or becoming homeless who were allocated EFA between July 2019 and December 2020, with the average household receiving nearly $2,000.

Recipients were chosen from among a larger group of people eligible for the program based on their vulnerability to homelessness and on a randomized system set up by LEO and Destination: Home. This temporary financial assistance helped pay rent, utilities, or other housing-related expenses on their behalf.

A common approach to fighting homelessness is to provide shelter to those who are already homeless, but the researchers argued that once a family or individual becomes homeless, they face even more difficulties—such as finding permanent housing, basic necessities, and health care. They are also more likely to become involved in the criminal justice system and experience frequent hospital visits. The study found that a preventive approach focusing directly on helping those who are on the brink of homelessness can also be effective.

“Our estimates suggest that the benefits to homelessness prevention exceed the costs,” the researchers say. They estimated that communities get $2.47 back in benefits per net dollar spent on emergency financial assistance.

“Policymakers at all levels are struggling to make really hard decisions about how to allocate scarce resources to address this pervasive problem,” Sullivan says. “But this study shows that you can actually target the intervention to those at risk, which moves the needle on homelessness enough to justify making the investment.”

While homelessness prevention programs are not a panacea to other problems often associated with the most visible forms of homelessness—such as health and substance abuse issues—it is still an effective way to help people, Phillips says.

“Every person who ends up homeless is a little different from the next, and the reasons they’re there are different, but it’s the kind of help they need at the moment they need it, before everything falls apart.”

One of LEO’s main tenets is to take a rigorous approach to fighting poverty by helping service providers apply scientific evaluation methods to better understand and share effective poverty interventions.

“A big part of LEO’s mission is to create evidence that helps improve the lives of those most vulnerable,” Sullivan says. “Because we have far greater needs than we have resources to address them, we have a real incentive to allocate those resources to the programs that are most effective. This evidence helps shape the decisions of those on the front lines fighting homelessness and poverty.”

The LEO study has implications both locally and nationally, says Jennifer Loving, chief executive officer of Destination: Home.

“This could inspire other jurisdictions to stand up their own homelessness prevention systems, using this research as a model or starting point for how to do that on their own—as well as justification to policymakers for funding,” Loving says.

The Santa Clara County Homelessness Prevention System relies on a partnership to help at-risk families and individuals maintain their housing by providing financial assistance as well as case management, legal assistance, financial counseling, and landlord dispute resolution. Destination: Home, one of the system’s lead organizations, gathers funding from the federal, county and city governments, as well as private foundations, and coordinates the efforts of a network of 19 nonprofit partners.

Source: University of Notre Dame