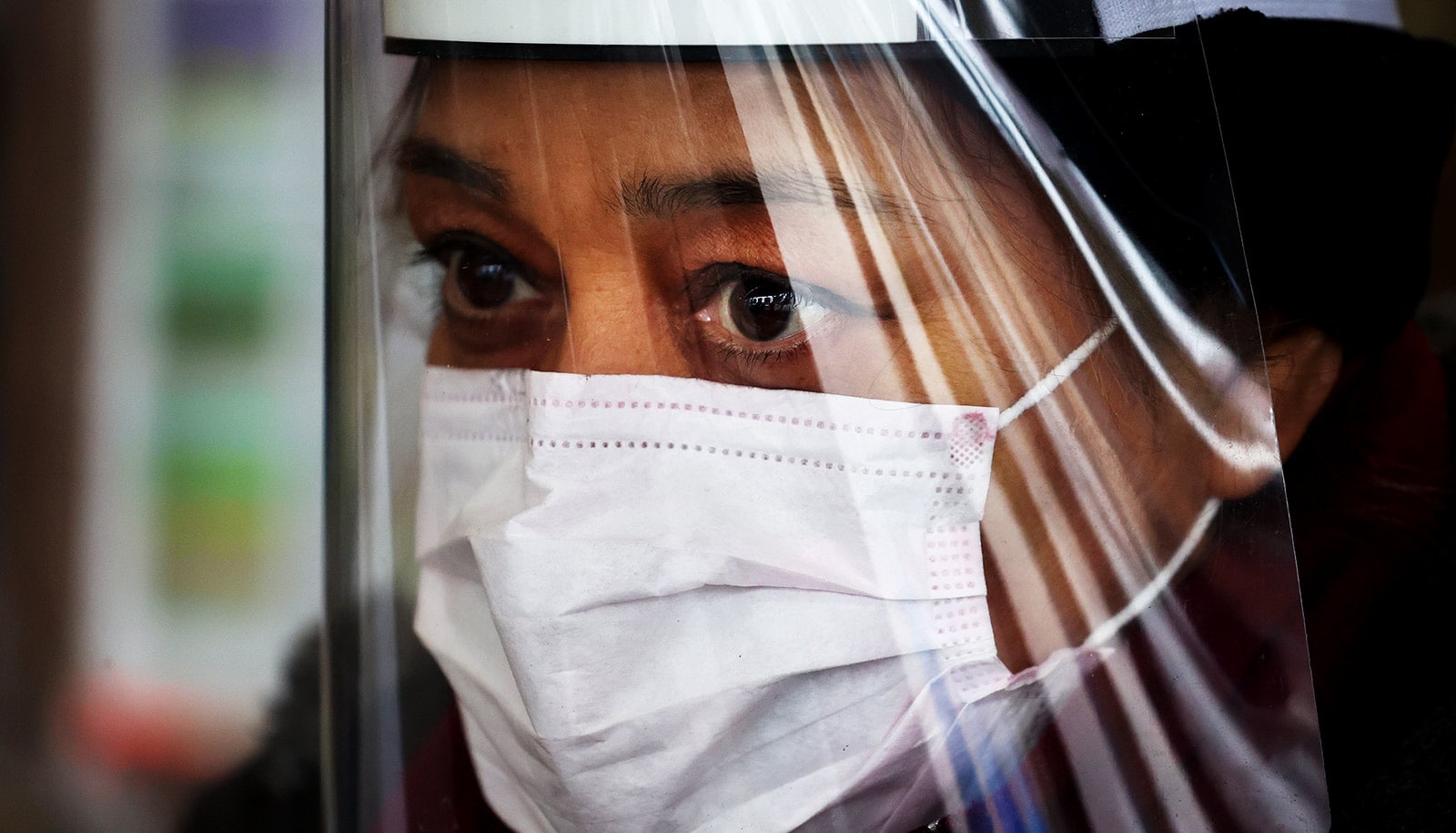

Women hold two-thirds of the jobs in the harshest category of work, according to new report on Washington workers during the pandemic.

The researchers looked at data on demographics, working conditions, wages and benefits, and risks of exposure to disease.

“The big takeaway from our research is how particularly women are working under precarious conditions,” says David West, coauthor of the report and an analyst at the Washington Labor Education and Research Center. “A large number of women are both facing safety risks at high-hazard jobs and are economically at risk.”

But as the state began its phased reopening, nonessential workers started returning to the workplace, and the researchers found that many of those workers also faced a high risk of exposure to disease and economic stress.

In the end, the researchers identified 55 of the 694 occupations on which they had data as both precarious—facing economic and health care stress—and high risk of exposure to the coronavirus. Out of a total Washington workforce of 3.3 million workers, some 900,000 fill positions in these 55 occupations. These workers, 70% in essential jobs, were not only mostly female, but also disproportionately workers of color.

“So, we really need to ensure that there are targeted policies or regulations to help these workers, especially since we now know who they are and what occupations and industries they fall into,” Baker says.

In order to determine which occupations were at higher risk of exposure to COVID-19 and to make specific recommendations related to workplace safety, the researchers looked at the importance of these “key dimensions” of a job:

- Physical proximity to others

- Dealings with external customers

- Face-to-face discussions

- Contact with others

- Exposure to disease/infections

- Work with a team or group

- Dealings with physically aggressive people

- Assisting/caring for others

- Performing for/working directly with the public

- Use of common or specialized safety equipment (gloves, masks, hazmat suits)

The authors list in their report a series of policies designed to address these health risks as well as the economic challenges they recommend policymakers and business leaders adopt.

Their key recommendations are:

- Airborne transmissible disease (ATD) standard: Washington should follow the lead of states such as California that have enacted ATD standards for their workplaces, instead of relying on voluntary guidance.

- Workplace coronavirus disclosure, testing, and tracking: Support comprehensive notification of positive workplace COVID tests, workplace testing, and prioritize workplace follow-up tracking.

- Safety committees: Promote and widely enforce the Washington state requirement that workplaces with more than 11 employees have safety committees in order to involve workers in identifying and preventing COVID risk factors.

- Economic security: Ensure that all Washington at-risk/precarious workers have affordable access to health insurance, hazard pay, paid leave for quarantine periods, and affordable child care to reduce stress and ensure prompt care.

“Even though this has been a devastating time for the American workforce,” Baker says, “we can harness this moment and make big structural changes that can forever improve the relationship between work and health.”

Mike Mulcahy of Working Title Research is a coauthor.

Source: University of Washington