Speeding up efforts to meet the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of limiting temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius could prevent thousands of extreme heat-related deaths in US cities, experts say.

The planet will warm by about 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century if the US and other nations meet only their current commitments under the Paris climate agreement to reduce emissions of heat-trapping gases, according to new research.

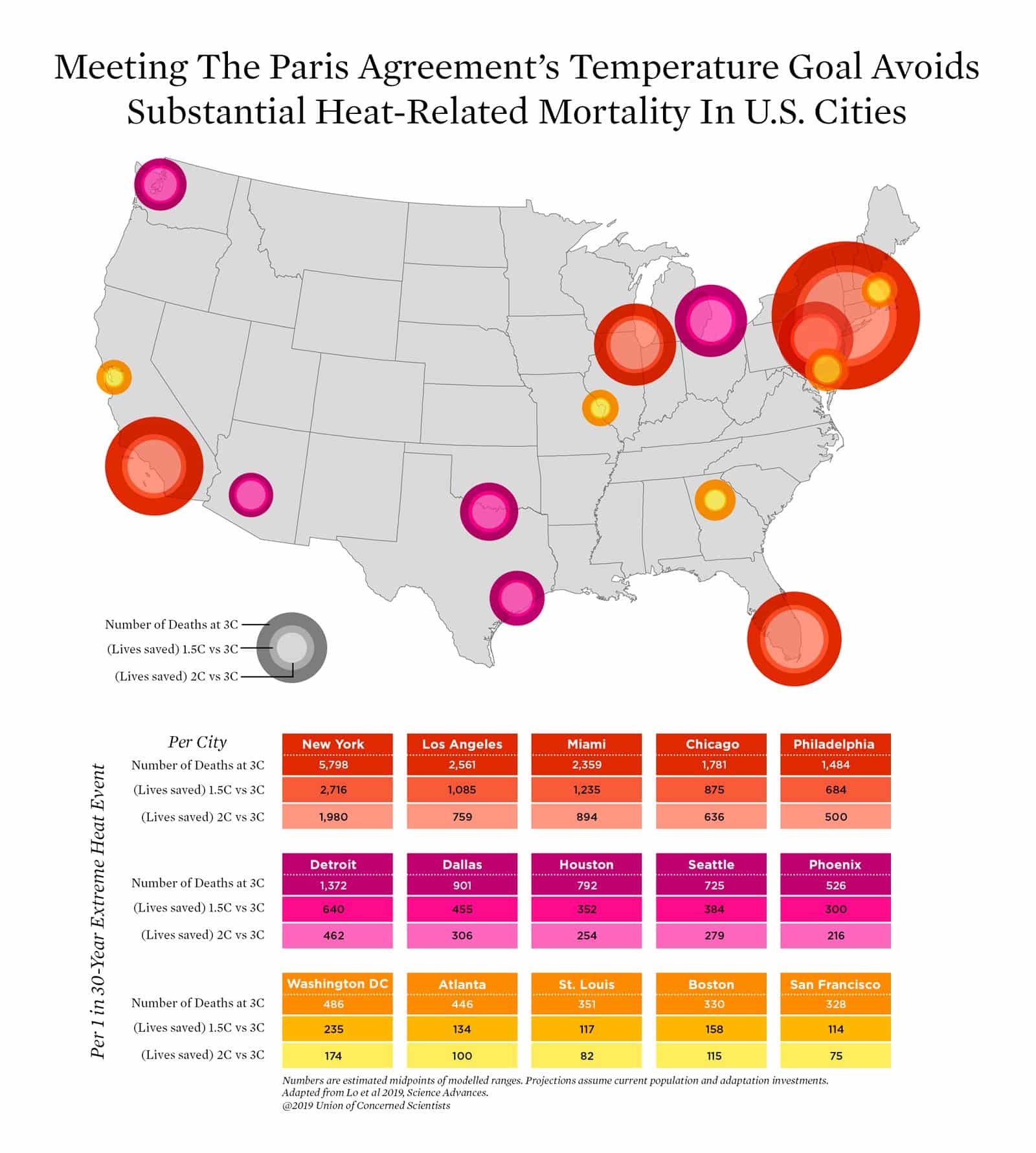

The first-of-its-kind study in Science Advances examines the impact on mortality rates of projected high temperatures associated with extreme heat expected to occur once every 30 years on average in 15 US cities: Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Francisco, Seattle, St. Louis, and Washington, DC.

“Climate change is not only affecting faraway places but also the United States,” says Eunice Lo of the University of Bristol. “As temperatures rise, exposure of major US cities to extreme heat will increase and more heat-related deaths will occur.

“The United States has emitted the largest amount of carbon dioxide in the world since the 18th century. Immediate and drastic emissions cuts are key to preventing large increases in heat-related deaths in the country.”

Saving lives

Climate change is already increasing the severity of extreme heat. If global temperature increases reach 3 degrees Celsius, these cities would experience more severe heat waves than if temperature rise is limited to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius. The study used the different high temperatures experts project under three warming scenarios for 1-in-30-year events in each city.

At 3 degrees Celsius, there would be between about 330 and 5,800 heat-related deaths per city for each 1-in-30-year event, with cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and Philadelphia facing the highest number of fatalities.

“All heat-related deaths are potentially preventable.”

Limiting global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius avoids between about 70 and 1,980 extreme heat-related deaths per city. Achieving the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold could avoid even more heat related deaths—between about 110 and 2,720, researchers say.

“This study shows that taking urgent action to reduce carbon pollution will save lives in cities across the United States,” says Peter Frumhoff, director of science and policy and chief climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Urban design and urban heat islands

“The government also has an obligation to help communities prepare for life in a world that’s heating up. This could include making air conditioning more available especially to those with low or fixed incomes, strengthening our health care system, and increasing awareness of heat-related health risks.”

“All heat-related deaths are potentially preventable,” says Kristie L. Ebi, professor and researcher at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. “We need urgent investment in heat wave early warning and response systems and other options to protect the most vulnerable as temperatures continue to rise.

“Older adults, children, and outdoor workers are among those populations particularly susceptible to higher temperatures. In the long term, urban planning must prioritize design changes that decrease urban heat islands and ensure our infrastructure is prepared for unprecedented temperatures.”

The numbers of avoided heat-related deaths in the analysis may be a conservative estimate, as they rely on current population data. Therefore, they cannot account for an aging population, increases in urbanization, exacerbation of the urban heat island effect, or other demographic factors that could change and contribute to added heat vulnerability, the researchers say.

Source: University of Washington