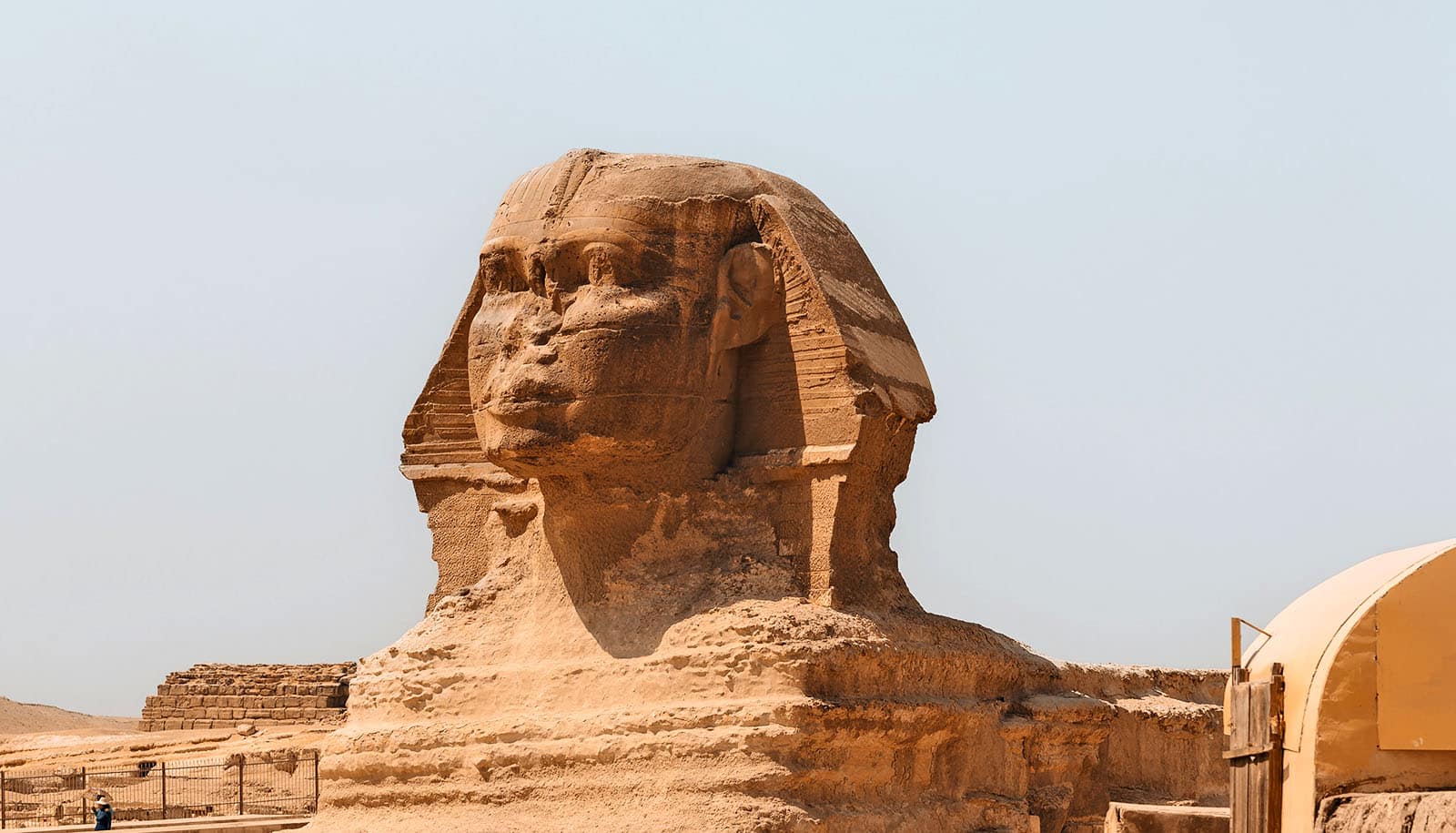

Researchers have replicated conditions that existed 4,500 years ago to show how wind moved against rock formations to possibly shape the Great Sphinx of Giza.

Historians and archaeologists have, over centuries, explored the mysteries behind the Great Sphinx: What did it originally look like? What was it designed to represent? What was its original name?

But less attention has been paid to a foundational, and controversial, question: What was the terrain the ancient Egyptians came across when they began to build this instantly recognizable structure—and did these natural surroundings have a hand in its formation?

“Our findings offer a possible ‘origin story’ for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” says Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences and senior author of the study, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Fluids.

“Our laboratory experiments showed that surprisingly Sphinx-like shapes can, in fact, come from materials being eroded by fast flows.”

The work centered on replicating yardangs—unusual rock formations found in deserts resulting from wind-blown dust and sand—and exploring how the Great Sphinx could have originated as a yardang that was subsequently detailed by humans into the form of the widely recognized statue.

To do so, Ristroph and his colleagues in NYU’s Applied Mathematics Laboratory took mounds of soft clay with harder, less erodible material embedded inside—mimicking the terrain in northeastern Egypt, where the Great Sphinx sits.

They then washed these formations with a fast-flowing stream of water—to replicate wind—that carved and reshaped them, eventually reaching a Sphinx-like formation. The harder or more resistant material became the “head” of the lion and many other features—such as an undercut “neck,” “paws” laid out in front on the ground, and arched “back”—developed.

“Our results provide a simple origin theory for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” says Ristroph. “There are, in fact, yardangs in existence today that look like seated or lying animals, lending support to our conclusions.”

“The work may also be useful to geologists as it reveals factors that affect rock formations—namely, that they are not homogeneous or uniform in composition,” he adds. “The unexpected shapes come from how the flows are diverted around the harder or less-erodible parts.”

The National Science Foundation supported the work.

Source: NYU