A minimally invasive biosensor system could help people better manage gout, say researchers.

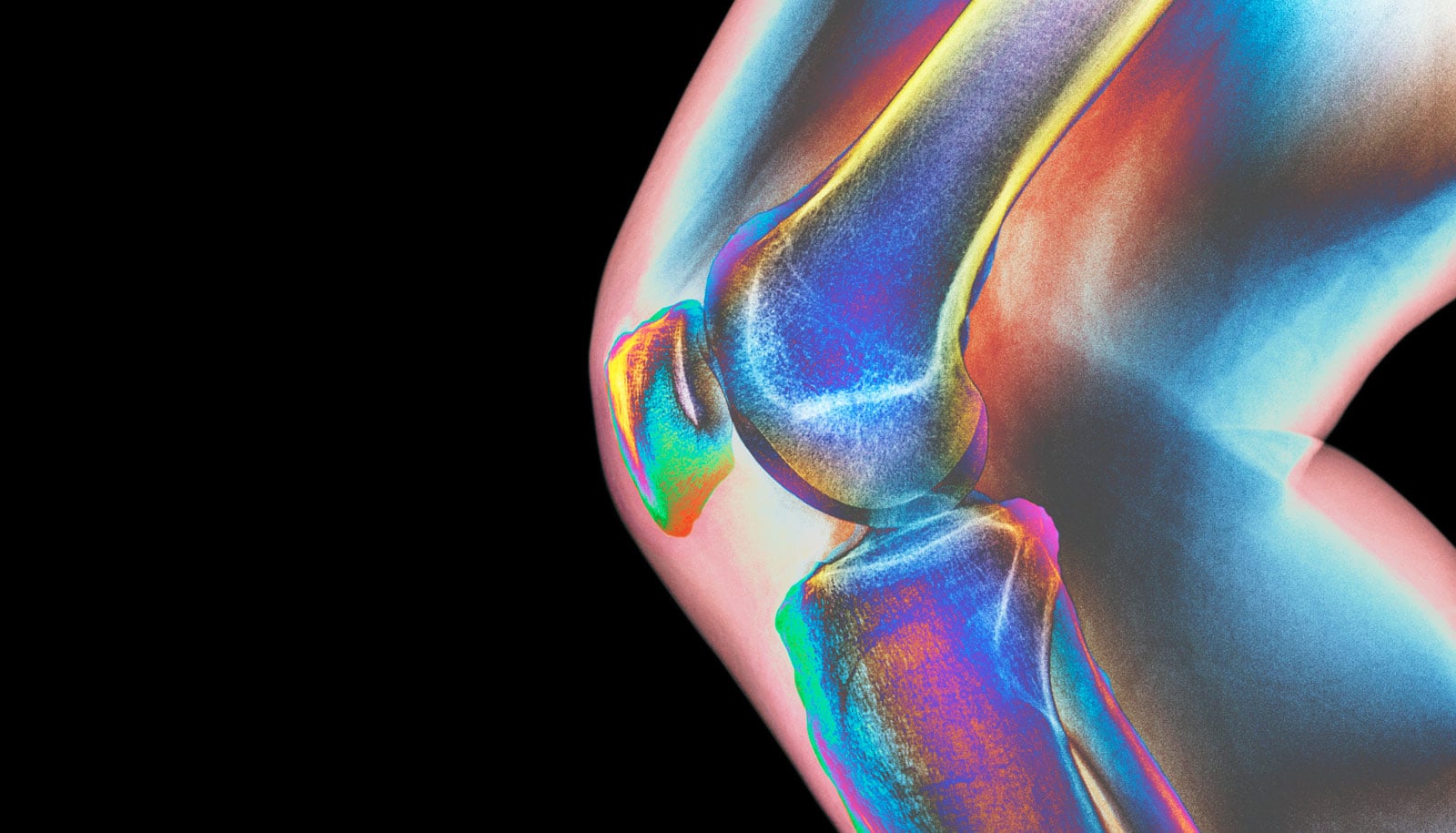

Gout is a painful joint disease that affects over 8 million Americans. Patients with gout tend to have higher levels of urate salts circulating in their bloodstream, a condition called hyperuricemia. These urate crystals then diffuse out of blood vessels and accumulate in the space between joints. The salt deposits then cause excruciating pain, and in advanced cases, a deterioration of joints and bones.

The researchers, who report their work in the journal sensors, say their minimally invasive biosensor system may hold the key to future point-of-care therapies centered on personal management of gout, and possibly other conditions.

“Finding more ways to help patients reduce their risks of gout attacks is an important clinical need that hasn’t been looked at in detail,” says Mike McShane, department head and professor in the department of biomedical engineering at Texas A&M University.

“In the future, biosensor technology such as ours can potentially help patients take preemptive steps to reduce the severity of their symptoms and lower their long-term health costs from repeated lab visits.”

For gout diagnosis, physicians often use clinical criteria, like the frequency of painful incidents, location of pain, and the severity of the inflammation. But for a definitive diagnosis, the fluid between the joints is examined for the presence and quantity of urate crystals. These laboratory tests can be expensive and time-consuming due to factors such as equipment and labor costs. Also, the researchers say frequent visits for laboratory testing can be difficult for elderly gout patients.

However, levels of circulating urate can be kept in check with medications. Additionally, avoiding or minimizing the consumption of foods rich in urates, like red meat and seafood, can also help in managing blood urate levels.

“Maintaining low levels of urate is critical for mitigating gout symptoms,” says Tokunbo Falohun, a graduate student in the College of Engineering and the primary author of the study. “And so, we wanted to create a technology that is reliable and user-friendly so that patients can easily self-monitor their blood urate levels.”

Urate reacts with oxygen in the presence of an enzyme called uricase to form allantoin. The researchers used this knowledge to develop a system where urate levels could be indirectly monitored using benzoporphyrins, a known sensor for oxygen.

Benzoporphyrins are complex molecules that have unique optical properties that are valuable in the design of optical biosensors. When hit by light from an LED, benzoporphyrins get energized, and after a short time, lose their excess in stages and finally emit light. But oxygen atoms can affect the amount of time or lifetimes of benzoporphyrins in an energized state.

Through collisions, oxygen atoms can take away some of the excess energy from the benzoporphyrins. And so, if there are fewer oxygen atoms, there are fewer that bump into benzoporphyrins and the lifetimes of benzoporphyrins proportionately increase. The researchers reasoned that when urate levels are high, benzoporphyrins lifetimes must be higher since more oxygen is used up to make allantoin.

Based on this rationale, McShane and Falohun set up a technology to measure benzoporphyrins’ lifetimes. Their technology consisted of two main components: an optical device to both produce light and collect emitted light from benzoporphyrins; and a biocompatible hydrogel platform for encapsulating uricase and benzoporphyrins.

To mimic conditions within the body, the researchers put the pieces of hydrogels, which were thin discs millimeters in diameter, in saline-filled chambers receiving a steady flow of oxygen and continually maintained at 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit). In each chamber, they then put in different levels of urate. An external computer connected to the optical system calculated and reported the lifetimes of the benzoporphyrins.

The researchers found that when they switched on the LED light, as predicted, the urate levels in each chamber directly affected the lifetimes of the benzoporphyrins. That is if there was more urate, there were fewer oxygen atoms available for collisions and consequently, the lifetimes of the benzoporphyrins were higher.

Although the lifetime values faithfully followed urate levels, McShane and Falohun say that additional experiments need to be done to ensure long-term stability of their optical biosensor system so that the technology is suitable for future clinical use.

However, they note that their biosensor system demonstrates the feasibility of using the technology for personal management of gout since the hydrogels are small enough to be inserted just below the skin, at a site near oxygen-carrying blood vessels. Furthermore, they say the optical system can be easily connected to any standard computer and that their software is designed to report urate levels in a user-friendly manner. Thus, gout patients will be able to measure their urate levels precisely and as often as they need to.

“From a global health perspective, we need to empower people to make informed decisions about their health and well-being. In that regard, our system is a step toward building biomedical technologies for continuous and more frequent monitoring of disease symptoms,” says McShane.

The National Science Foundation and the Texas A&M University Diversity Fellowship support the work.

Source: Texas A&M University