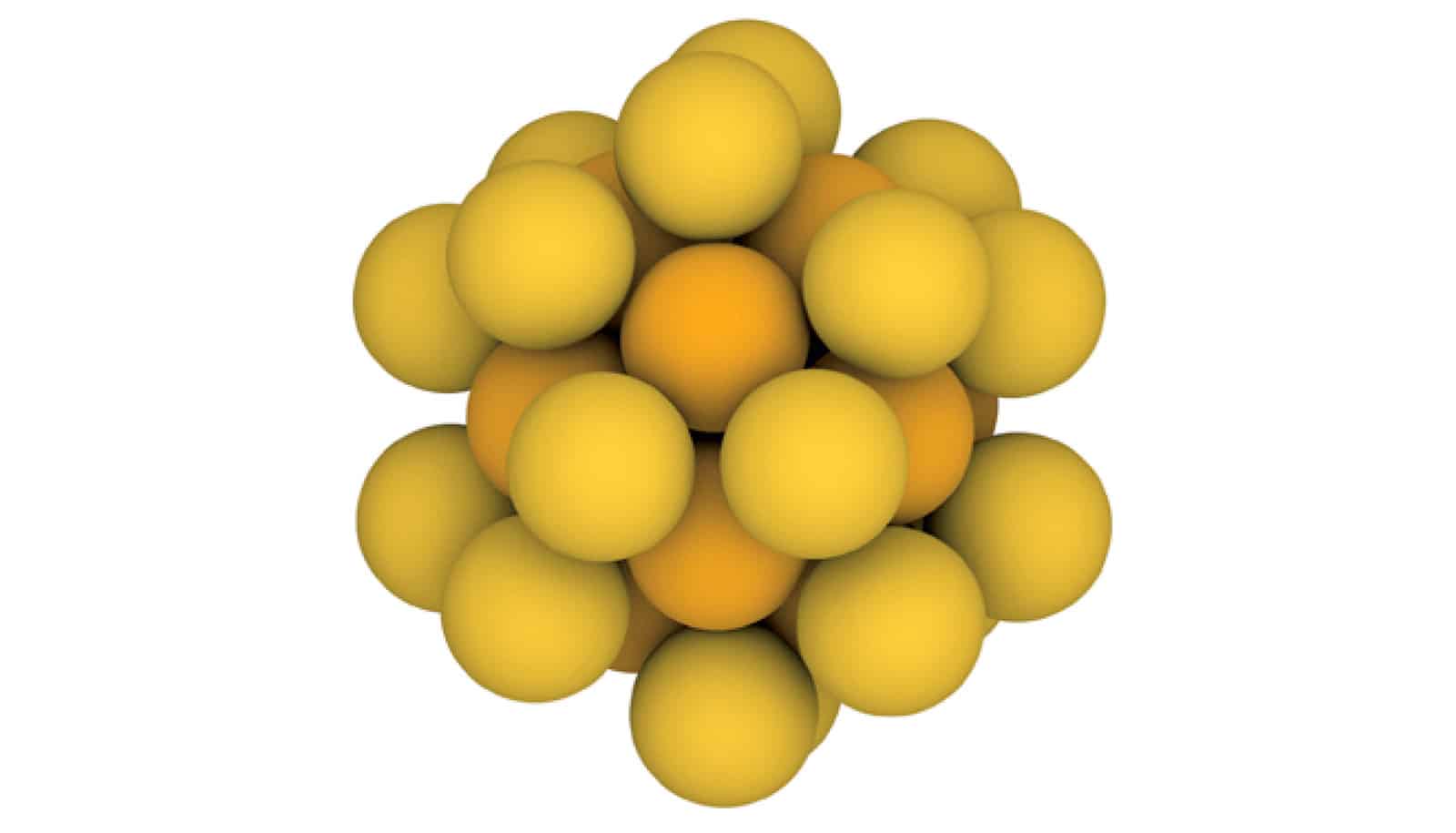

Chemists have discovered that tiny gold “seed” particles, a key ingredient in one of the most common nanoparticle recipes, are one and the same as gold buckyballs, 32-atom spherical molecules.

Carbon buckyballs are hollow 60-atom molecules that were co-discovered and named by the late Rice chemist Richard Smalley. He dubbed them “buckminsterfullerenes” because their atomic structure reminded him of architect Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, and the “fullerene” family has grown to include dozens of hollow molecules.

In 2019, Rice chemists Matthew Jones and Liang Qiao discovered that golden fullerenes are the gold “seed” particles chemists have long used to make gold nanoparticles. The find came just a few months after the first reported synthesis of gold buckyballs, and it revealed chemists had unknowingly been using the golden molecules for decades.

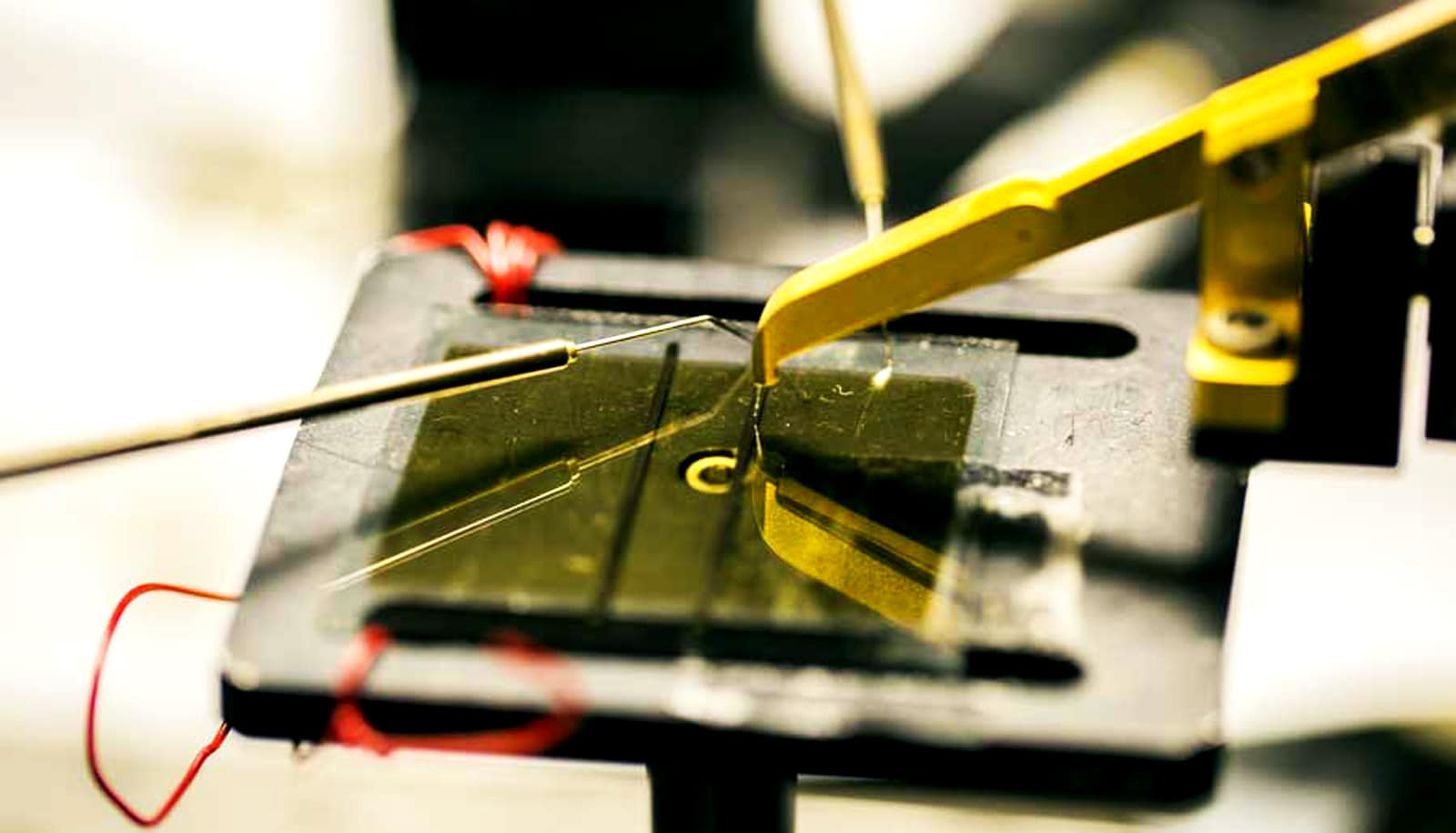

“What we’re talking about is, arguably, the most ubiquitous method for generating any nanomaterial,” Jones says. “And the reason is that it’s just so incredibly simple. You don’t need specialized equipment for this. High school students can do it.”

Jones, Qiao and coauthors spent years compiling evidence to verify the discovery and recently published their results in Nature Communications.

Jones, an assistant professor in chemistry and materials science and nanoengineering, says the knowledge that gold nanoparticles are synthesized from molecules could help chemists uncover the mechanisms of those syntheses.

“That’s the big picture for why this work is important,” he says.

Jones says researchers discovered in the early 2000s how to use gold seed particles in chemical syntheses that produced many shapes of gold nanoparticles, including rods, cubes, and pyramids.

“It’s really appealing to be able to control particle shape, because that changes many of the properties,” Jones says. “This is the synthesis that almost everyone uses. It’s been used for 20 years, and for that whole period of time, these seeds were simply described as ‘particles.'”

Jones and Qiao, a former postdoctoral researcher in Jones’ lab, weren’t looking for gold-32 in 2019, but they noticed it in mass spectrometry readings. The discovery of carbon-60 buckyballs happened in a similar way.

Confirming that the widely used seeds were gold-32 molecules rather than nanoparticles took years of effort, including state-of-the-art imaging by Yimo Han’s research group at Rice and detailed theoretical analyses by the groups of both Rigoberto Hernandez at Johns Hopkins University and Andre Clayborne at George Mason University.

“Nanoparticles are typically similar in size and shape, but they are not identical,” Jones says. “If I make a batch of 7-nanometer spherical gold nanoparticles, some of them will have exactly 10,000 atoms, but others might have 10,023 or 9,092.

“Molecules, on the other hand, are perfect,” he says. “I can write out a formula for a molecule. I can draw a molecule. And if I make a solution of molecules, they are all exactly the same in the number, type, and connectivity of their atoms.”

Jones says nanoscientists have learned how to synthesize many useful nanoparticles, but progress has often come via trial and error because “there is virtually no mechanistic understanding” of their synthesis.

“The problem here is pretty straightforward,” he says. “It’s like saying, ‘I want you to bake me a cake, and I’m gonna give you a bunch of white powders, but I’m not going to tell you what they are.’ Even if you have a recipe, if you don’t know what the starting materials are, it’s a nightmare to figure out what ingredients are doing what.

“I want nanoscience to be like organic chemistry, where you can make essentially whatever you want, with whatever properties you want,” Jones says.

He says organic chemists have exquisite control over matter “because chemists before them did incredibly detailed mechanistic work to understand all of the precise ways in which those reactions operate. We are very, very far from that in nanoscience, but the only way we’ll ever get there is by doing work like this and understanding, mechanistically, what we’re starting with and how things form. That’s the ultimate goal.”

The Welch Foundation, the Packard Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and Rice supported the work.

Source: Rice University