New research addresses one of the challenges in the longstanding quest to achieve fusion.

The work will enhance the accuracy of computer models used in simulations of laser-driven implosions.

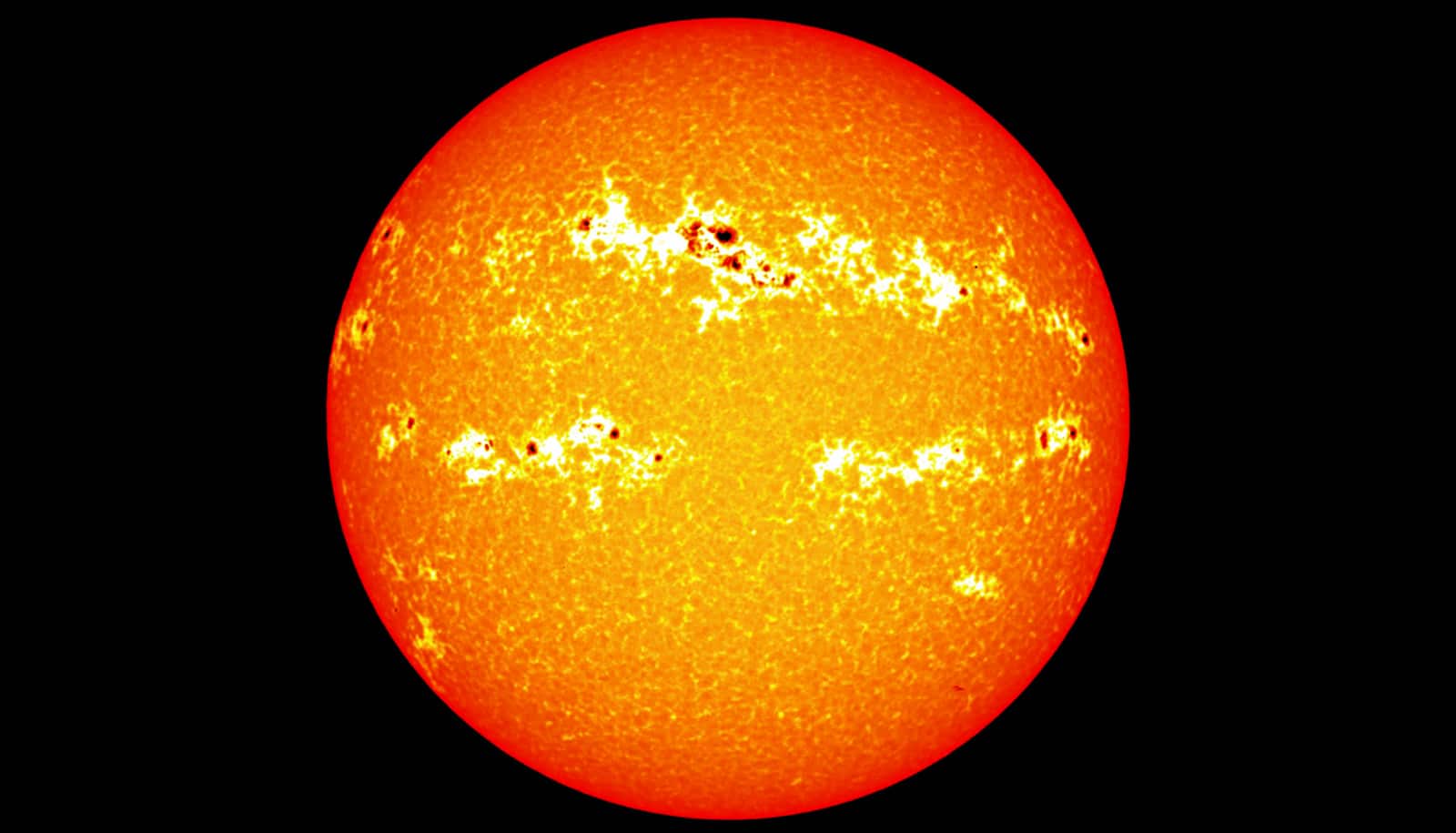

In laser-driven inertial confinement fusion (ICF) experiments, such as those conducted at the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE), short beams consisting of intense pulses of light—pulses lasting mere billionths of a second—deliver energy to heat and compress a target of hydrogen fuel cells. Ideally, this process would release more energy than it took to heat the system.

Laser-driven ICF experiments require that many laser beams propagate through a plasma—a hot soup of free moving electrons and ions—to deposit their radiation energy precisely at their intended target. But, as the beams do so, they interact with the plasma in ways that can complicate the intended result.

“ICF necessarily generates environments in which many laser beams overlap in a hot plasma surrounding the target, and it has been recognized for many years that the laser beams can interact and exchange energy,” says David Turnbull, an LLE scientist and the first author of the paper in Nature Physics.

To accurately model this interaction, scientists need to know exactly how the energy from the laser beam interacts with the plasma. While researchers have offered theories about the ways in which laser beams alter a plasma, none has ever been demonstrated experimentally.

Now, researchers at the LLE, along with colleagues at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in France, have directly demonstrated for the first time how laser beams modify the conditions of the underlying plasma, in turn affecting the transfer of energy in fusion experiments.

Researchers often use supercomputers to study the implosions involved in fusion experiments. It is important, therefore, that these computer models accurately depict the physical processes involved, including the exchange of energy from the laser beams to the plasma and eventually to the target.

For the past decade, researchers have used computer models describing the mutual laser beam interaction involved in laser-driven fusion experiments. However, the models have generally assumed that the energy from the laser beams interacts in a type of equilibrium known as Maxwellian distribution—an equilibrium one would expect in the exchange when no lasers are present.

“But, of course, lasers are present,” says Dustin Froula, a senior scientist at the LLE.

Froula notes that scientists predicted almost 40 years ago that lasers alter the underlying plasma conditions in important ways. In 1980, a theory predicted these non-Maxwellian distribution functions in laser plasmas due to the preferential heating of slow electrons by the laser beams. In subsequent years, Rochester graduate Bedros Afeyan predicted that the effect of these non-Maxwellian electron distribution functions would change how laser energy is transferred between beams.

But lacking experimental evidence to verify that prediction, researchers did not account for it in their simulations.

Turnbull, Froula, and physics and astronomy graduate student Avram Milder conducted experiments at the Omega Laser Facility at the LLE to make highly detailed measurements of the laser-heated plasmas. The results of these experiments show for the first time that the distribution of electron energies in a plasma is affected by their interaction with the laser radiation and can no longer be accurately described by prevailing models.

The new research not only validates a longstanding theory, but also shows that laser-plasma interaction strongly modifies the transfer of energy.

“New inline models that better account for the underlying plasma conditions are currently under development, which should improve the predictive capability of integrated implosion simulations,” Turnbull says.

This research is based upon work that the US Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority supported.

Source: University of Rochester