About 250 million years ago, a reptile with a playpus-style bill swam the shallow seas in what is now China. It used the cartilaginous bill to find prey by touch, according to new research.

No animal alive today looks quite like a duck-billed platypus, a semi-aquatic, egg-laying mammal from eastern Australia, but the newly discovered reptile was similar, at least when it comes to its bill.

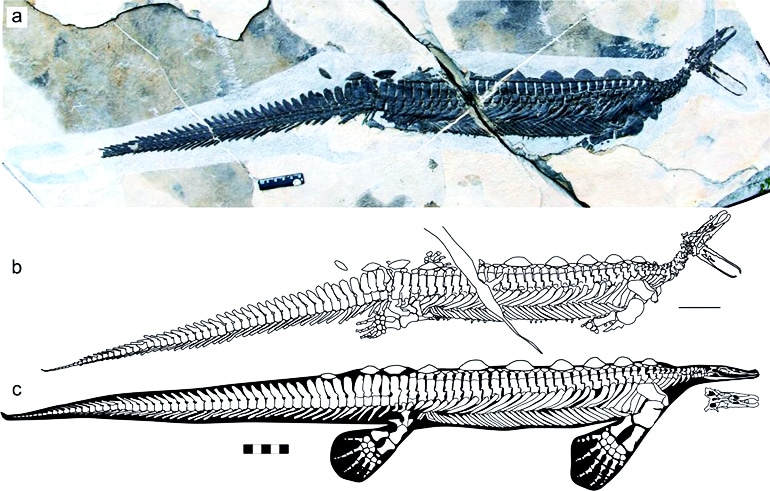

The marine reptile, called Eretmorhipis carrolldongi, is from the lower Triassic period. Researchers describe the discovery in the journal Scientific Reports.

Apart from its platypus-like bill, Eretmorhipis was about 70 centimeters long with a long, rigid body, small head and tiny eyes, and four flippers for swimming and steering. Bony plates ran down the animal’s back.

Researchers previously knew Eretmorhipis only from partial fossils without a head, says coauthor Ryosuke Motani, a paleontologist in the earth and planetary sciences department at the University of California, Davis.

“This is a very strange animal,” Motani says. “When I started thinking about the biology I was really puzzled.”

The two new fossils show the animal’s skull had bones that would have supported a bill of cartilage. Like the modern platypus, there is a large hole in the bones in the middle of the bill. In the platypus, the bill is filled with receptors that allow it to hunt by touch in muddy streams.

In the early Triassic, a shallow sea, about a meter deep, covered the area over a carbonate platform extending for hundreds of miles. Researchers found Eretmorhipis fossils at what were deeper holes, or lagoons, in the platform. There are no fossils to show what Eretmorhipis ate, but it likely fed on shrimp, worms, and other small invertebrates, Motani says.

Its long, bony body means that Eretmorhipis was probably a poor swimmer, Motani says.

“It wouldn’t survive in the modern world, but it didn’t have any rivals at the time,” he says.

Related to the dolphinlike ichthyosaurs, Eretmorhipis evolved in a world devastated by the mass extinction event at the end of the Permian era. The fossil provides more evidence of rapid evolution occurring during the early Triassic, Motani says.

Additional coauthors came from Wuhan Centre of China Geological Survey, Peking University, Università degli Studi di Milano, and the Field Museum. The China Geological Survey, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Ministry of Science and Technology supported the research.

Source: UC Davis