How did the apple from the Garden of Eden become the “forbidden fruit” symbolizing temptation, sin, and the fall of man?

“‘Adam and Eve ate a pom,’ meant ‘Adam and Eve ate a fruit.’ Over time, however, the meaning of pom changed.”

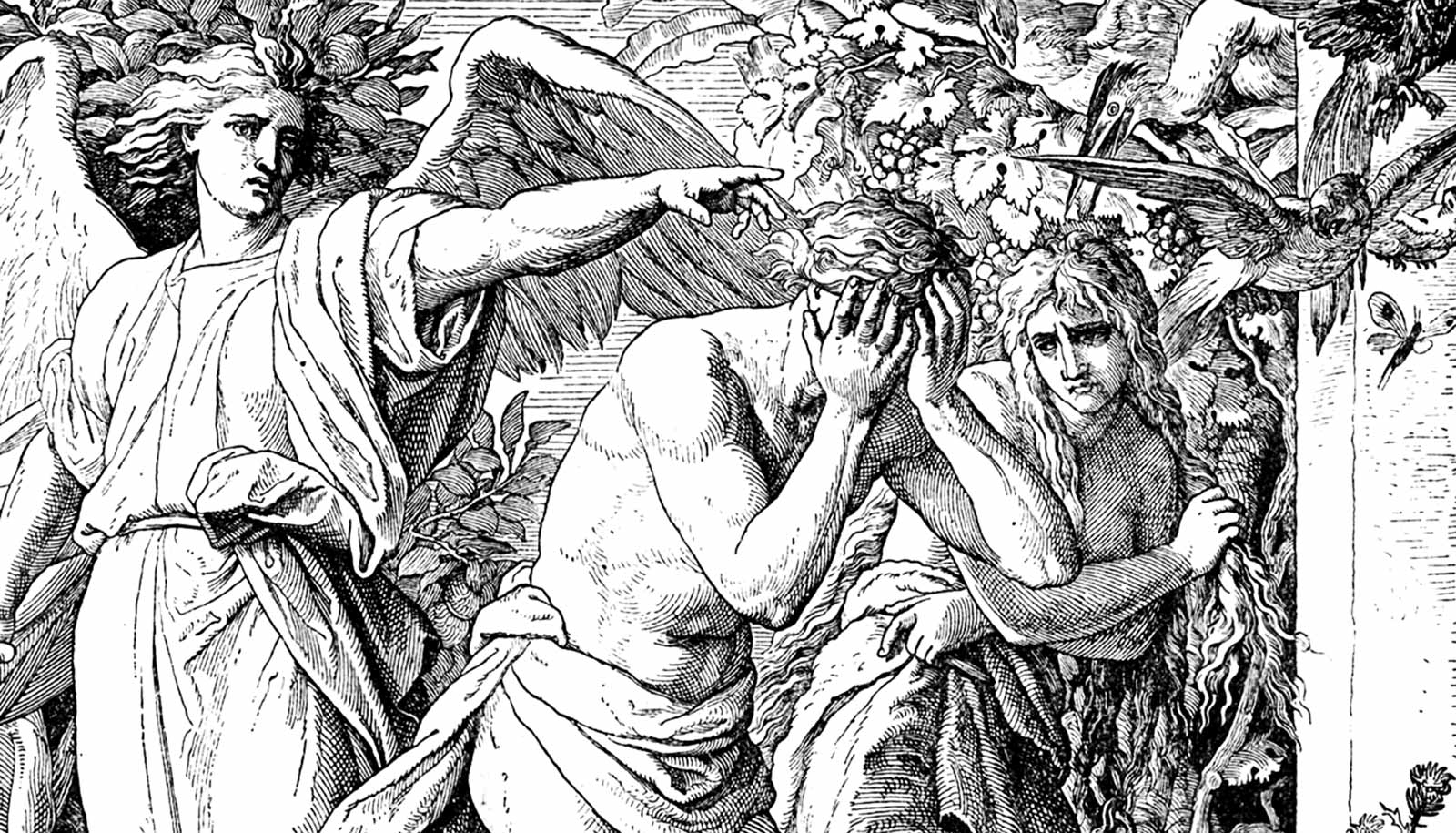

An attention-grabbing Super Bowl ad looked at what would have happened if Adam and Eve ate an avocado instead of an apple. Although a spoof, the Bible never actually specifies what Adam and Eve ate in the Garden of Eden.

Azzan Yadin-Israel, a professor of Jewish studies and classics at Rutgers University, tackles the question in his new book Temptation Transformed: The Story of How the Forbidden Fruit Became an Apple (University of Chicago Press, 2022).

Here, Yadin-Israel unpacks the evolution of the identity of the forbidden fruit:

What does the Bible say about the forbidden fruit?

Although the idea that Adam and Eve ate an apple is common today, the Book of Genesis never mentions the identity of the forbidden fruit. This led to a great deal of speculation among early Jewish and Christian commentators, and several species became popular candidates, such as the fig and the grape, first and foremost, but also the pomegranate and the citron.

How did the apple enter the conversation?

Since at least the 17th-century, scholars have agreed that the answer is to be found in a quirk of the Latin language. The Latin word for apple is “malum,” which happens to be a homonym of the Latin word for “evil.” Since, the argument goes, the forbidden fruit caused the fall of man and humanity’s expulsion from paradise, it is certainly a terrible malum (“evil”). So what fruit is a more likely candidate than the malum, “apple”? This view has become received wisdom and is found in scholarly works across fields and disciplines.

Is there more to the story?

It turns out that this explanation has no support in the Latin sources. I read through all the major (and many of the minor) medieval Latin commentators to the Book of Genesis, and pretty much no one refers to this play on words. More perplexing, even as late as the 14th century, the commentators don’t identify the forbidden fruit with the apple. They still reference the fig and the grape, and sometimes other fruit species.

Where and when does the apple tradition appear?

To answer this question, I examined the artistic representation of the fall of man scene, trying to determine where and when artists begin to portray the forbidden fruit as an apple. The answer was France in the 12th century, and from there to other countries. But why?

The answer comes from an unexpected place—historical linguistics. Latin authors most commonly refer to the forbidden fruit as a pomum, a Latin word meaning “fruit” or “tree fruit.” Not surprisingly, Old French, which descends from Latin, has the word “pom” (modern French “pomme”), which originally meant “fruit” as well, and was used in the earliest Old French translations of Genesis.

“Adam and Eve ate a pom,” meant “Adam and Eve ate a fruit.” Over time, however, the meaning of pom changed. Rather than a broad, general term for “fruit,” it took on a narrower meaning: “apple.” Once that change in meaning became widely accepted, readers of the Old French version of Genesis understood the statement “Adam and Eve ate a pom” to mean “Adam and Eve ate an apple.” At that point, they understood the apple to be the fruit that the Bible itself identified as the forbidden fruit and began representing it in these terms.

What is the ultimate takeaway from your findings?

Most scholars have assumed that the emergence of the apple as the self-evident forbidden fruit must be driven by theological or religious considerations. If my argument is correct, the change occurred as the result of forces that are completely indifferent to these matters. It was a general shift in the meaning of an Old French word that happened to have ramifications for the best-known symbol in the Hebrew Bible.

Source: Rutgers University