A new food “fingerprint” technique is sensitive enough to distinguish between foods made from the same ingredients, but in different locations.

When you shell out for artisanal food—Swiss Gruyère cheese, organic vanilla extract, Italian prosciutto—did you get what you paid for? With global food fraud estimates as high as $40 billion a year, it’s a question researchers are tackling with the new technique.

“We’re talking about an enormous criminal enterprise that is almost unnoticed.”

Food fraud, which the US Food and Drug Administration officially terms “economically motivated adulteration,” occurs when manufacturers substitute a cheaper ingredient for one that is more valuable, like cutting olive oil with vegetable oil, or bulking saffron with ground plant stems. It’s a tough crime to catch as foods can be altered anywhere along a global supply chain. Ensuring authenticity is even more difficult when dishonest purveyors simply swap a similar product for its more expensive counterpart, like Himalayan sea salt, or San Marzano tomatoes.

“Think about the difference between a free-range ham from Portugal, aged in a cave for two years, and a ham you buy at WalMart,” says Bartek Rajwa, a research professor of computational life sciences at Purdue University. “They are both pig meat, the same ingredients, but they have a very different taste, smell, and texture. To tell them apart, we need a system that can quantitatively analyze those characteristics. It’s a big challenge.”

Rajwa and his team are developing a patent-pending two-part process to provide information about the atomic composition and chemical structure of a food sample, enough to pinpoint the ingredients, the preparation, and, potentially, the point of origin.

Published results from a test using the first step as a standalone method were 99% accurate in distinguishing imitation vanilla flavoring from real vanilla extract, and about 90% accurate in identifying European cheese branded as “Gruyère” versus a Gruyère-style cheese produced in Wisconsin.

Earlier this year, Rajwa presented the more sophisticated two-part process at the Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Sensing for Agriculture and Food Quality and Safety XV conference.

Rajwa, an expert in biological analysis techniques, stumbled upon the field of food authentication as part of his work developing systems to recognize bacterial contamination of foods.

“I started going to food science conferences and listening to leaders in the field, and that’s when I realized the scale of the problem,” Rajwa says. “We’re talking about an enormous criminal enterprise that is almost unnoticed. Most of the time the only harm is that you’re paying a premium and getting a product of inferior quality, but there are instances in which it can cause serious harm.”

Many spectroscopy methods, including mass spectrometry, fluorescence spectroscopy, and liquid chromatography are used to identify food. However, Rajwa says, none of the existing methods are fool-proof, and most are difficult and expensive, leaving ample room for innovation in the field.

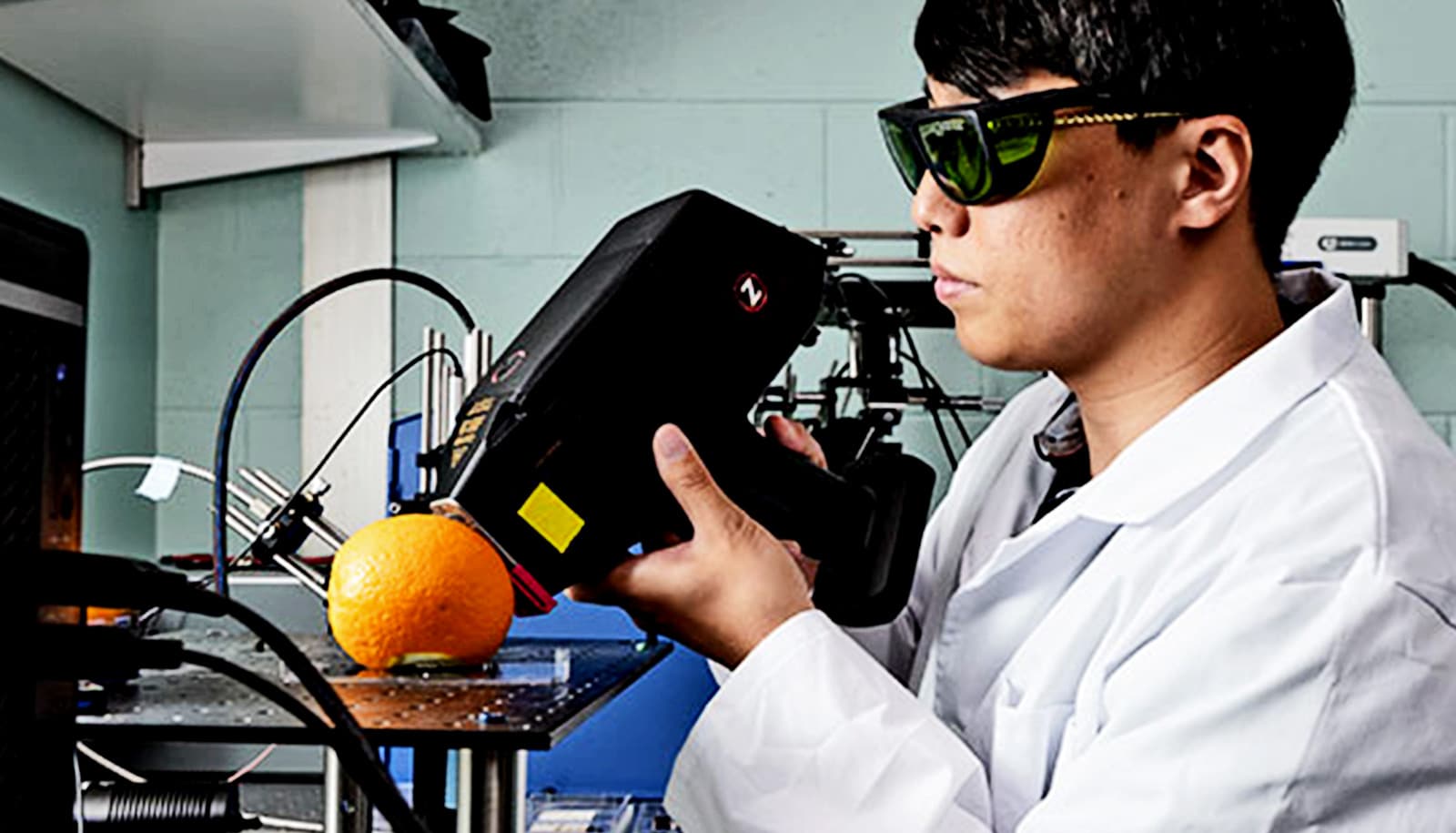

To meet the challenge, Rajwa and collaborators J. Paul Robinson and Euiwon Bae turned to Laser Induced Breakdown Spectrosopy (LIBS), a method that’s well developed for use in material science and metallurgy, but not commonly used in food science.

LIBS uses a high-powered laser to create a tiny plume of plasma at the surface of a sample. The intensity of different wavelengths of light emitted by the plasma indicates the type and proportion of elements that make up the ingredients in the sample and even provides some valuable information on its texture. LIBS creates a unique digital spectrum, which, with a machine-learning approach Rajwa’s team developed for the task, is processed into a fingerprint that can be used to verify the identity of the food tested.

In a paper published in Foods, the team tested several samples of Alpine-style cheese, coffee, vanilla extract, balsamic vinegar, and spices like nutmeg, pepper, and turmeric. For many foods, the method was highly accurate, even when using an inexpensive portable handheld LIBS instrument. But for more complex foods, like the Alpine-style cheese, Rajwa says, the LIBS spectrum isn’t enough.

For additional information that can help verify the origin of even complex foods like cheese and ham, he is working on a second step using Raman spectroscopy, which is capable of identifying specific organic molecules, such as those associated with the presence of pesticides, fungicides, or antibiotics in food.

“In a sense, they form this complementary pair; what one cannot detect, the other can,” Rajwa says. “LIBS gives you the amount of each atom, and Raman tells you how they are organized.”

At the SPIE conference, Rajwa presented data with the two-part method showing improvements in accuracy over LIBS as a standalone method; final results have not yet been published.

This research was funded by the US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, and with the help of SciAps Inc., which supplied portable LIBS instruments. Rajwa disclosed the innovation to the Purdue Research Foundation Office of Technology Commercialization, which has applied for a patent on the intellectual property.

Source: Purdue University