Sixty-five million years ago, clouds of ash choked the skies over Earth. Dinosaurs, along with about half of all the species on Earth, staggered and died.

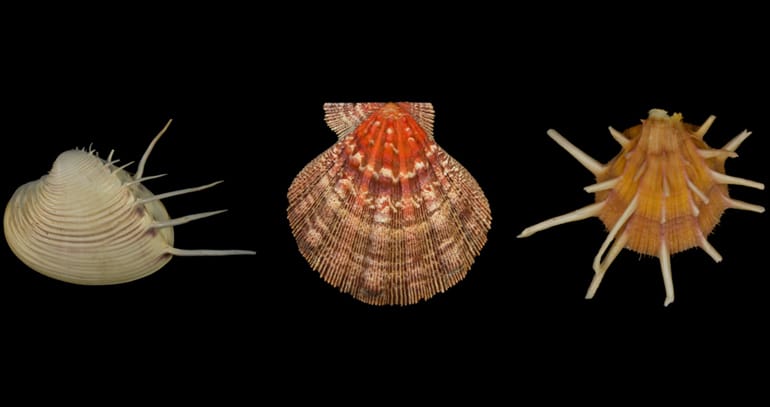

But in the seas, a colorful population of marine bivalves—the group including oysters, clams, and scallops—soldiered on, tucked into the crevices of ocean floors and shorelines. Though they also lost half their species, curiously, at least one species in each ecological niche survived.

University of Chicago scientists document this surprising trend in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Though the mass extinction wiped out staggeringly high numbers of species, they barely touched the overall “functional” diversity—how each species makes a living, be it filtering phytoplankton or eating small crustaceans, burrowing or clamping onto rocks.

The same held true for the biggest mass extinction of all, 250 million years ago: more than 90 percent of all species on Earth died out, but no modes of life disappeared.

Today’s biodiversity loss

Strangely, the scientists say, this differs from another kind of biodiversity loss: the loss of species today as you move from the warm tropics to the chillier poles. The number of species drops 80 percent to 95 percent from the tropics to the cold, snowy north and south, and functional variety also declines by 50 percent to 60 percent. Thus losing diversity due to changed environment is entirely possible—all the more reason why it’s strange to see such a pattern of survival in mass extinctions.

“The big question is: Given that we’re working on a mass extinction right now, which flavor will it be?”

“Multicellular life almost didn’t make it out of the Paleozoic era, but every functional group did. Then we see that functional diversity drops way down from tropics to poles; it parallels species loss in a way that’s totally different from the big extinctions. That’s wild—really fascinating and unexpected and strange,” says coauthor David Jablonski, professor of geophysical sciences.

This could have implications for how the mass extinction currently gathering steam could unfold and how badly it will affect Earth ecosystems, the authors say.

Jablonski and graduate student Stewart Edie, who is the first author of the paper, ran the numbers for two major mass extinctions in history: the relatively gradual end-Paleozoic extinction, perhaps driven by changing climates and ocean composition, and later, the sharper end-Cretaceous extinction, thought to be caused by a meteor impact and/or volcanic eruptions. Though they are very different stresses, the same pattern emerged.

“The rug gets pulled out from underneath all the species,” says Edie. “The landscape of the world completely and suddenly changed, making it all the more surprising that all functional types survived. Even the functional groups with only one or two species somehow make it through.”

Delicate balance

The question is pressing because functional diversity is what makes ecosystems tick. Ecosystems are delicately balanced, and losing ecological roles throws a system out of whack: Think of a forest damaged when the deer population explodes because the wolves that prey on them are removed. That balance keeps soil fertile, oceans full of fish, and grass growing for livestock.

Meteor that killed dinos may have sped up bird evolution

“The big question is: Given that we’re working on a mass extinction right now, which flavor will it be?” Jablonski says. “Will we have a tropic-to-poles type, where we lose half our functional groups and so ecosystems are massively altered? Or will it be a mass extinction where you can lose all these species, but the functional groups still somehow manage to limp on? We need to understand this.”

The other author of the paper is James W. Valentine with the University of California, Berkeley. Funding came from the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Source: University of Chicago