Thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have gotten a rare look at a young, Jupiter-sized planet that is growing by feeding off material surrounding a young star 370 light years from Earth.

“We just don’t know very much about how giant planets grow,” says Brendan Bowler, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin.

“This is the youngest bona fide planet Hubble has ever directly imaged.”

“This planetary system gives us the first opportunity to witness material falling onto a planet. Our results open up a new area for this research.”

Though more than 4,000 exoplanets have been cataloged, only about 15 have been directly photographed by telescopes. And the planets are so far away and small that they simply look like dots even in the best photos. The team’s fresh technique for using Hubble to directly image this planet paves a new route for further exoplanet research, especially during a planet’s formative years.

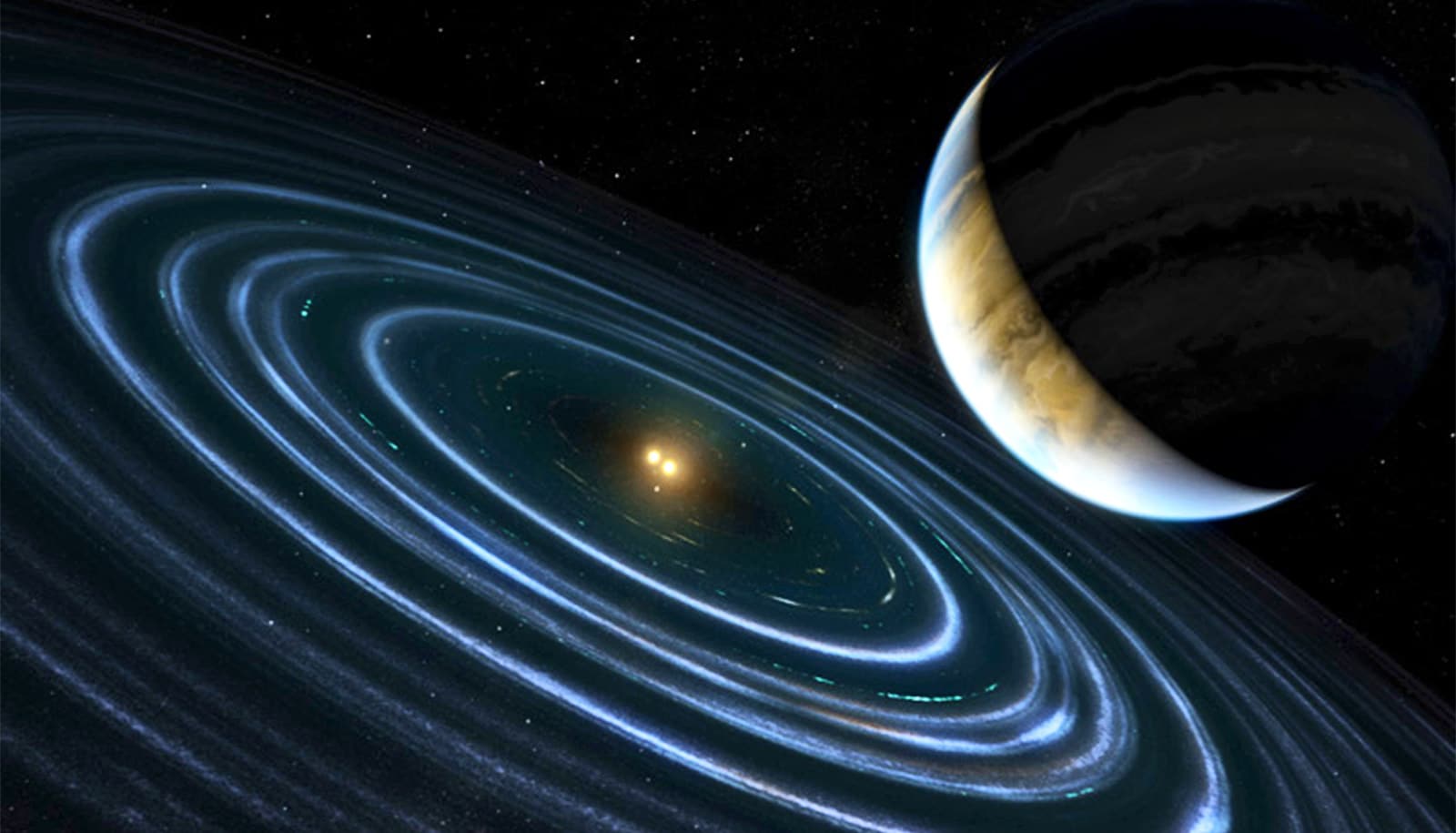

This huge exoplanet, designated PDS 70b, orbits the orange dwarf star PDS 70, which is already known to have two actively forming planets inside a huge disk of dust and gas encircling the star.

“This system is so exciting because we can witness the formation of a planet,” says Yifan Zhou, a postdoctoral researcher with the McDonald Observatory. “This is the youngest bona fide planet Hubble has ever directly imaged.” At a youthful 5 million years, the planet is still gathering material and building up mass.

Hubble’s ultraviolet light (UV) sensitivity offers a unique look at radiation from extremely hot gas falling onto the planet. The UV observations allowed the team to directly measure the planet’s mass growth rate for the first time. The remote world has already bulked up to five times the mass of Jupiter over a period of about 5 million years. The present measured accretion rate has dwindled significantly.

Zhou and Bowler emphasize that these observations are a single snapshot in time—more data are required to determine whether the rate at which the planet is adding mass is increasing or decreasing. Their measurements suggest that the planet is at the end of its formation process.

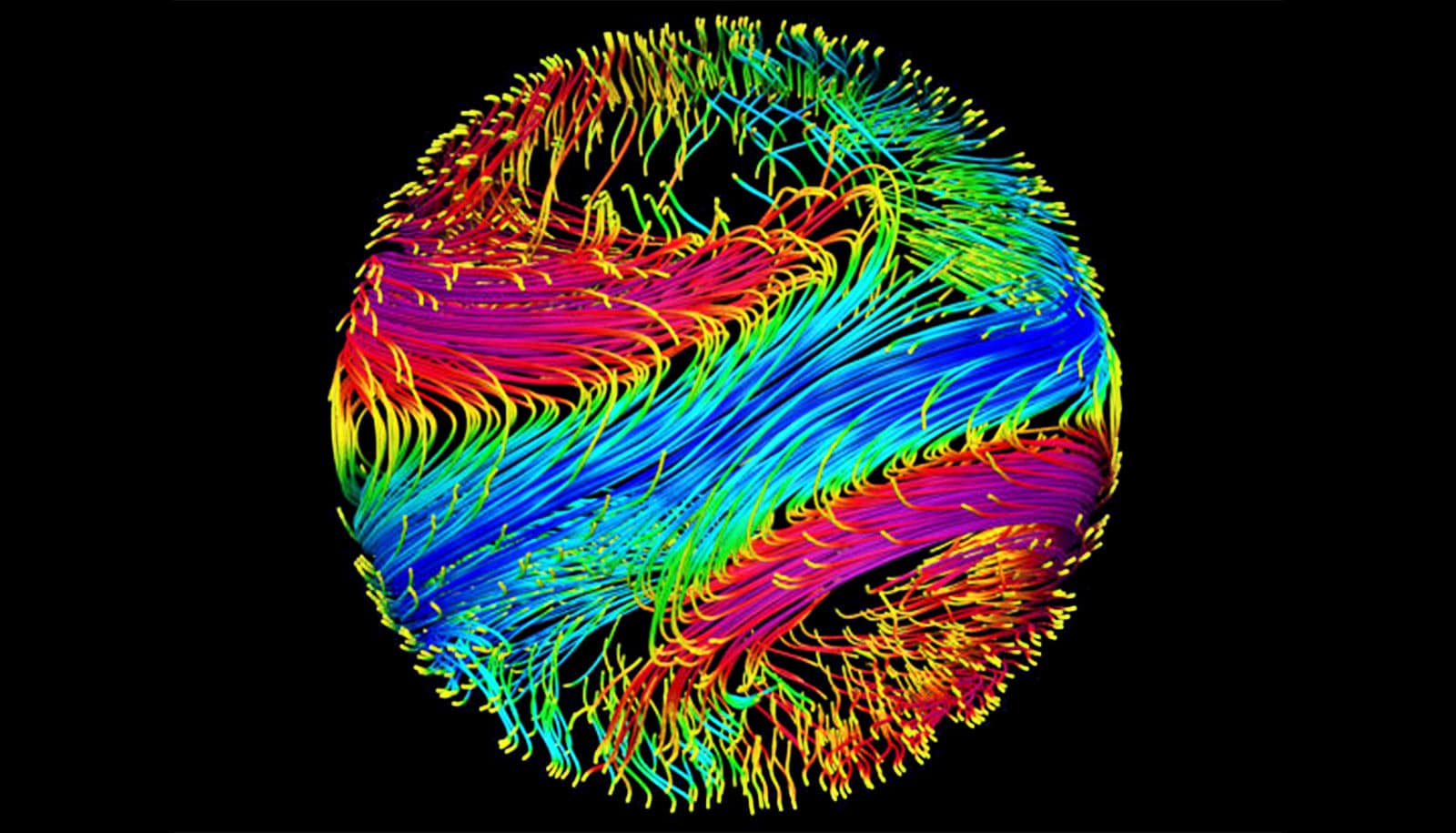

The youthful PDS 70 system is filled with a primordial gas-and-dust disk that provides fuel to feed the growth of planets throughout the entire system. The planet PDS 70b is encircled by its own gas-and-dust disk that’s siphoning material from the vastly larger disk around the star. The researchers hypothesize that magnetic field lines extend from the planet’s disk down to its atmosphere and are funneling material onto the planet’s surface.

“If this material follows columns from the disk onto the planet, it would cause local hot spots,” Zhou says. “These hot spots could be at least 10 times hotter than the temperature of the planet.”

The observations offer insights into how gas giant planets formed around our sun 4.6 billion years ago. Jupiter may have bulked up on a surrounding disk of infalling material. Its major moons would have also formed from leftovers in that disk.

A challenge to the team was overcoming the glare of the parent star. PDS 70b orbits at about the same distance as Uranus does from the sun, but its star is more than 3,000 times as bright as the planet at UV wavelengths. As Zhou processed the images, he carefully removed the star’s glare to leave behind only light emitted by the planet. In doing so, he improved the limit of how close a planet can be to its star in Hubble observations by a factor of five.

“Thirty-one years after launch, we’re still finding new ways to use Hubble,” Bowler says. “Yifan’s observing strategy and post-processing technique will open new windows into studying similar systems, or even the same system, repeatedly with Hubble. With future observations, we could potentially discover when the majority of the gas and dust falls onto their planets and if it does so at a constant rate.”

The results appear in The Astronomical Journal.

Source: UT Austin