Air pollution—especially ozone air pollution—accelerates the progression of emphysema of the lung, according to a new study.

While previous studies have shown a clear connection between air pollutants and some heart and lung diseases, new research in JAMA demonstrates an association between long-term exposure to all major air pollutants—especially ozone—with an increase in emphysema seen on lung scans.

Emphysema is a condition in which destruction of lung tissue leads to wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath, and increases the risk of death.

The results are based on an extensive, 18-year study involving more than 7,000 people and a detailed examination of the air pollution they encountered between 2000 and 2018 in six metropolitan regions in the US: Chicago; Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Baltimore; Los Angeles; St. Paul, Minnesota; and New York City. Researchers drew the participants from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Air and Lung studies.

“To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to assess the association between long-term exposure to air pollutants and progression of percent emphysema in a large, community-based, multi-ethnic cohort,” says first author Meng Wang, an assistant professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the University at Buffalo School of Public Health and Health Professions, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington.

“We were surprised to see how strong air pollution’s impact was on the progression of emphysema on lung scans, in the same league as the effects of cigarette smoking, which is by far the best-known cause of emphysema,” says senior coauthor Joel Kaufman, professor of environmental and occupational health sciences in the University of Washington’s School of Public Health.

Emphysema and pollution exposure

Ambient ozone levels that were 3 parts per billion higher where study participants lived compared to another location over a period of 10 years associated with an increase in emphysema roughly the equivalent of smoking a pack of cigarettes a day for 29 years.

Further, the study determined that ozone levels in some major US cities are increasing by that amount, due in part to climate change. The annual averages of ozone levels in study areas ranged between about 10 and 25 ppb.

“Rates of chronic lung disease in this country are going up and increasingly it is recognized that this disease occurs in nonsmokers,” says Kaufman. “We really need to understand what’s causing chronic lung disease, and it appears that air pollution exposures that are common and hard to avoid might be a major contributor.”

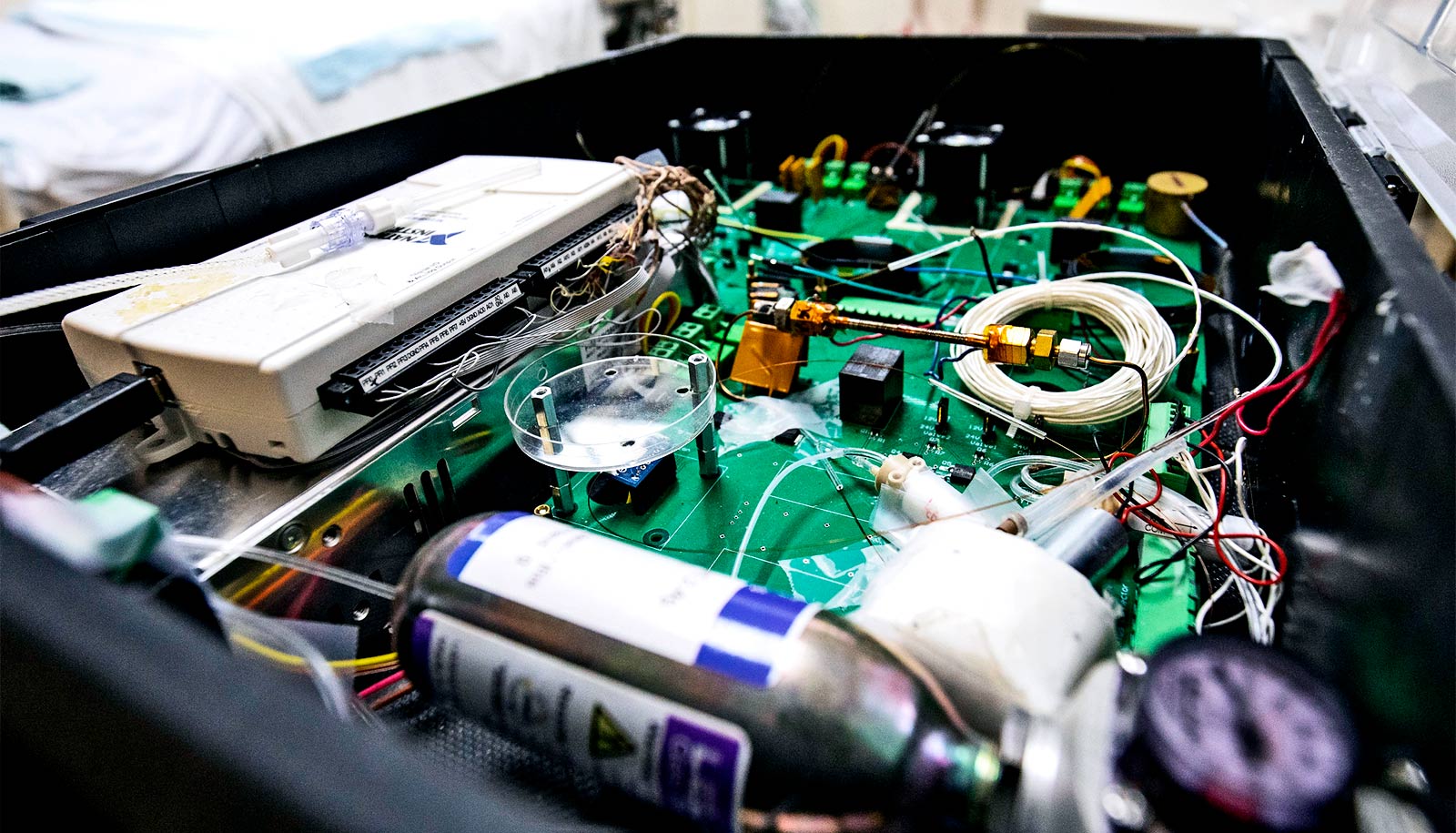

Researchers developed new and accurate exposure assessment methods for air pollution levels at the homes of study participants, collecting detailed measurement of exposures over years in these metropolitan regions, and measurements at the homes of many of the participants.

While most of the airborne pollutants are in decline because of successful efforts to reduce them, ozone has increased, the study shows. Ground-level ozone is mostly produced when ultraviolet light reacts with pollutants from fossil fuels.

Ozone on the rise

“This is a big study with state-of-the-art analysis of more than 15,000 CT scans repeated on thousands of people over as long as 18 years,” says senior author R. Graham Barr, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Columbia University.

“These findings matter since ground-level ozone levels are rising, and the amount of emphysema on CT scans predicts hospitalization from and deaths due to chronic lung disease. As temperatures rise with climate change, ground-level ozone will continue to increase unless steps are taken to reduce this pollutant. But it’s not clear what level of the air pollutants, if any, is safe for human health.”

Researchers measured emphysema from CT scans that identify holes in the small air sacs of the participants’ lungs, and lung function tests, which measure the speed and amount of air breathed in and out.

Source: University at Buffalo