DNA test results of large seizures of elephant ivory by law enforcement have linked multiple shipments to the same network of dealers, according to a new study.

The international trade in elephant ivory has been illegal since 1989, but African elephant numbers continue to decline. In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature cited ivory poaching as a primary reason for a staggering loss of about 111,000 elephants between 2005 and 2015—leaving their total numbers at an estimated 415,000.

The researchers linked these ivory shipments together after developing a rigorous sorting and DNA testing regimen for tusks in different ivory shipments. The method allowed scientists to identify tusk pairs that had been separated and shipped in different consignments to different destinations around the world—but had been shipped out of the same port, nearly always within 10 months of each other, with high overlap in the geographic origins of tusks in the matching shipments.

“Our prior work on DNA testing of illegal ivory shipments showed that the major elephant ‘poaching hotspots’ in Africa were relatively few in number,” says lead and corresponding author Samuel Wasser, a biology professor and director of the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington.

“Now, we’ve shown that the number and location of the major networks smuggling these large shipments of ivory out of Africa are also relatively few.”

The paper appears in Science Advances.

Cartel connections

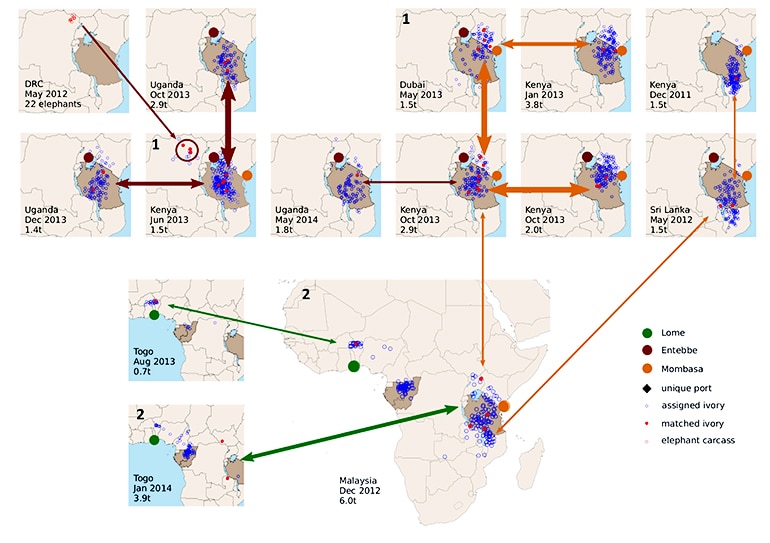

Using this protocol, the team identified what appear to be the three largest ivory smuggling cartels in Africa, operating out of Mombasa, Kenya; Entebbe, Uganda; and Lomé, Togo. Out of 38 large ivory shipments analyzed, the team was able to link 11 of these shipments together by identifying tusk pairs separated after poaching, yet shipped out of the same port during the 2011-2014 period when trafficking was at its peak.

Large shipments currently dominate the illegal ivory trade. About 70 percent of ivory seizures between 1996 and 2011 were in large consignments of at least half a metric ton, or about 0.55 US tons, according to a 2013 study in PLOS ONE.

Linking multiple large ivory shipments to the same smuggling networks will help build evidence against the cartels that are responsible for the bulk of illegal ivory trade and shipment, Wasser says. These efforts could add multiple counts of trafficking charges against the leaders of smuggling operations, who most often face trial for single, high-profile, and occasionally controversial events; the recent acquittal of Feisal Mohamed Ali in Kenya being a case in point.

“We reveal connections between what would otherwise be isolated ivory seizures—linking seizures not just to specific criminal networks operating in these ports, but to poaching and transport networks that funnel the tusks hundreds of miles to these cartels,” says Wasser. “It is an investigative tool to help officials track these networks and collect evidence for criminal cases.”

Poaching hotspots

Wasser and his team had previously developed DNA testing of large ivory shipments to identify what populations of African elephants poachers most targeted. For this endeavor, they created a “genetic reference map” of elephant populations across Africa, using DNA samples they extracted primarily from elephant dung.

Then, the researchers sampled ivory from elephant tusks law enforcement officials seized and extracted DNA from them. The researchers matched key regions in the ivory DNA samples to the genetic reference map, which let them identify the region that the elephant had come from, often to within about 300 kilometers, or about 186 miles.

In a 2015 paper published in Science, they announced that the bulk of seized tusks came from two “poaching hotspots” on the continent based on these DNA analyses.

While conducting those analyses, Wasser and his team developed a protocol to representatively subsample hundreds of tusks as efficiently as possible.

“We have neither the time nor the money to collect samples and extract DNA from every tusk in a shipment,” says Wasser. “We needed to find a way to sample only a fraction of the tusks in a shipment, but that method also needed to let us get a glimpse at the diversity of poached elephants within that shipment.”

Tusk fractions

In each large ivory seizure, they would identify pairs by sorting tusks by the diameter of the base, color, and gum line, which indicates where the lip rested on the tusk. This allowed the researchers to extract DNA from only one tusk in the pair.

Using this sorting approach, Wasser and his team noticed that many tusks in large shipments were orphans. The partner tusk was not present. But through comparing DNA samples from tusks among 38 large ivory consignments confiscated from 2011 to 2014, they matched up 26 pairs of tusks among 11 shipments, even though they were only testing, on average, about one-third of the tusks in each seizure.

“There is so much information in an ivory seizure—so much more than what a traditional investigation can uncover,” says Wasser. “Not only can we identify the geographic origins of the poached elephants and the number of populations represented in a seizure, but we can use the same genetic tools to link different seizures to the same underlying criminal network.”

Additional coauthors are from the University of Washington Center for Conservation Biology, the Forensic and Genetics Laboratory at the Kenya Wildlife Service, and the Malaysian Department of Wildlife, and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia. The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, the US Department of State, the UN Office of Drugs and Crime, the World Bank, the Woodtiger Fund, the Wildcat Foundation, INTERPOL, the Bosack Kruger Charitable Foundation, Paul and Yaffa Maritz, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Institute of Justice funded the work.

Source: University of Washington