A new computer model screens drugs for unintended cardiac side effects, especially arrhythmia risk, report researchers.

“One main reason for a drug being removed from the market is potentially life-threatening arrhythmias,” says study co-leader Colleen E. Clancy, professor of physiology and membrane biology at the University of California, Davis. “Even drugs developed to treat arrhythmia have ended up actually causing them.”

The problem, according to Clancy, is that there is no easy way to preview how a drug interacts with hERG-encoded potassium channels essential to normal heart rhythm.

“So far there has been no surefire way to determine which drugs will be therapeutic and which will harmful,” Clancy says. “What we have shown is that we can now make this determination starting from the chemical structure of a drug and then predicting its impact on the heart rhythm.”

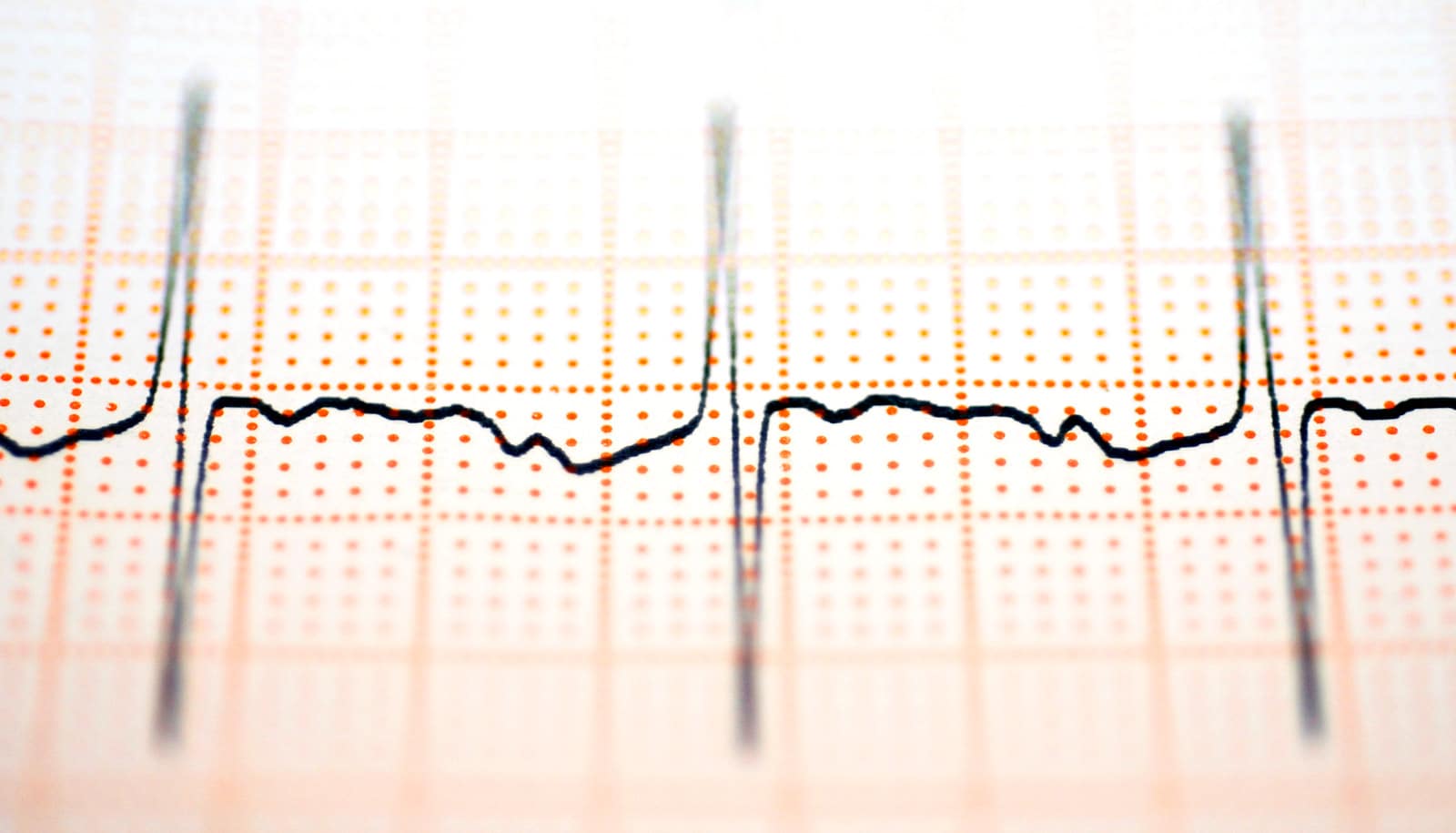

Using a drug’s chemical formula, the computer model reveals how that drug specifically interacts with hERG channels as well as cardiac cells and tissue. The outcomes can then be validated with comparisons to clinical data from electrocardiogram (ECG) results of patients. For the study, the researchers validated the model with ECGs of patients taking two drugs known to interact with hERG channels—one with a strong safety profile and another known to increase arrhythmias. The results proved the accuracy of the model.

Clancy envisions that the model will offer an essential pre-market test of cardiac drug safety. That test could ultimately be used for other organ systems such as the liver and brain.

“Every new drug needs to go through a screening for cardiac toxicity, and this could be an important first step to suggesting harm or safety before moving on to more expensive and extensive testing,” Clancy says.

Additional coauthors of the study, published in Circulation Research, are from UC Davis, American River College, and the University of Calgary.

Funding came from the National Institutes of Health, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the American Heart Association, the UC Davis department of physiology and membrane biology research partnership fund, the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, XSEDE Research Allocations, Compute Canada, and NCSA Blue Waters Broadening Participation Allocation.

Source: UC Davis