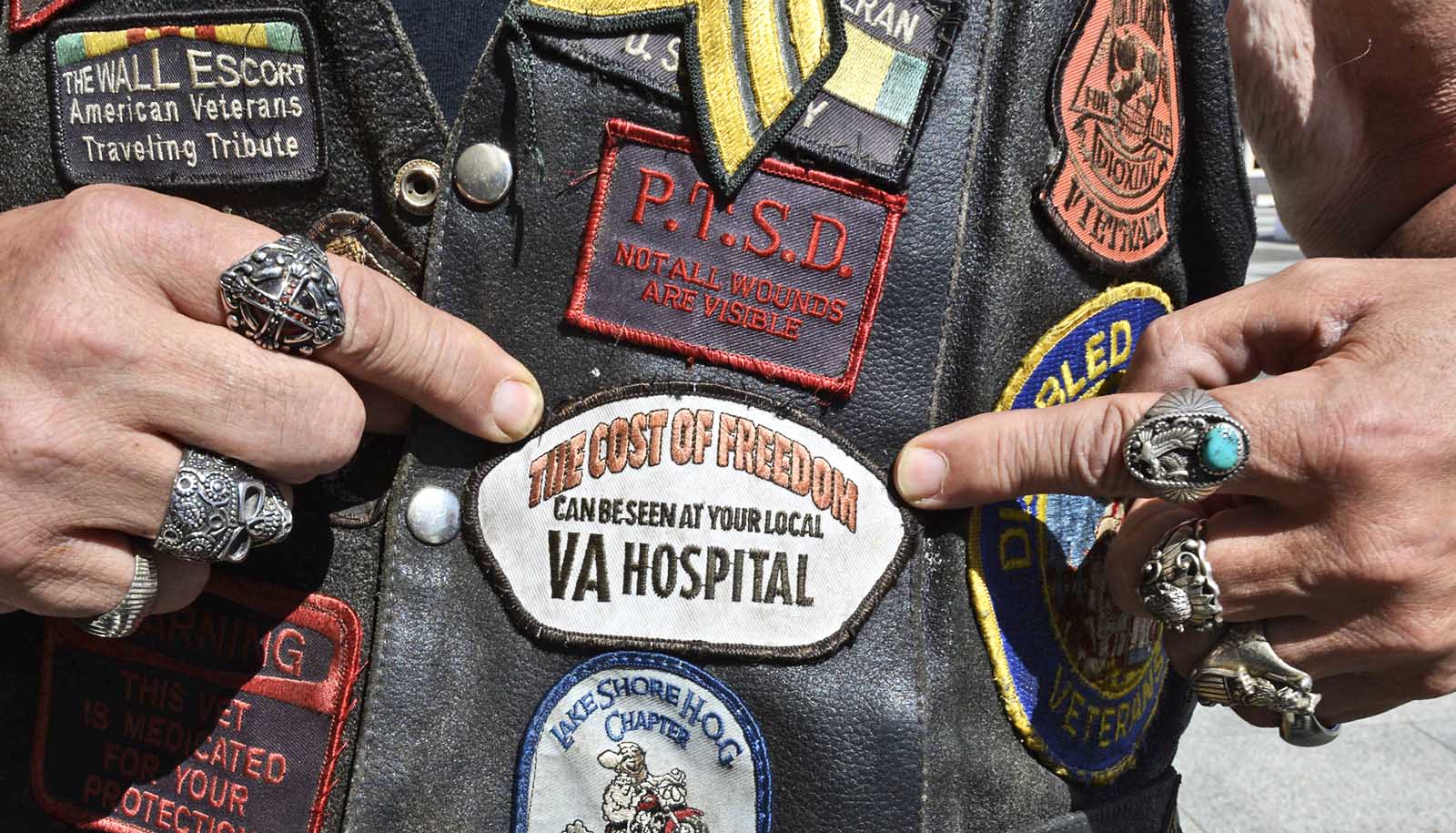

Disability compensation payments have a positive impact on veterans’ health, research finds.

A large study comparing Vietnam War-era military veterans who became eligible for disability compensation with ineligible veterans found that eligibility for compensation was associated with substantial reductions in hospitalizations—an important metric of overall health.

The longer the eligible veterans received disability payments, the greater the decline in hospitalizations was among that group, the researchers found. The study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, included 70,471 Vietnam War-era veterans.

“The takeaway is that there may be very important health benefits to receiving disability compensation,” says author Amal Trivedi, a professor of health services, policy, and practice and of medicine at Brown University.

The potential cost savings as a result of fewer hospitalizations should be considered in future changes to the federal Veterans Affairs disability compensation program, he adds. In 2020, more than 5 million veterans received a total of $91 billion in compensation for disabling conditions related to military service. The payments apply to individuals with lower socioeconomic status and worse health than the general population. The payments typically occur until a recipient’s death.

Because of the structure of the disability compensation program, Trivedi says, it stands to reason that it might have important effects on veterans’ health, especially considering the robust evidence of the association between income and health. However, there has been little research on the association between disability compensation and veteran’s health.

A change in VA disability policy in 2001 provided Trivedi and his research team the opportunity to examine the association between eligibility for disability compensation with mortality and hospitalizations among veterans with diabetes. The study merged data from the Veterans Health Administration, Veterans Benefits Association, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and Vietnam War-era military records from the Department of Defense. Most of the people in the study were male veterans with a diagnosis of diabetes and performed military service between 1961 and 1975.

The researchers examined changes in health outcomes for veterans in three equal periods: 2001 to 2006, 2007 to 2012, and 2013 to 2018. They note that annual disability compensation increased over these three time periods—compared to the non-eligible veterans, eligible veterans received $8,025, $14,412, and $17,162 more in benefits during the three periods, respectively.

Their analysis of the data found that among veterans concurrently enrolled in Medicare, eligibility for disability compensation was associated with substantial reductions in hospitalizations: a 10% decline in the first period, a 13% decline in the second period, and a 21% decline in the third period. The study found no association between eligibility for disability for compensation and lower mortality.

This study did not examine the reasons for this health effect. However, Trivedi says that in his position as a physician at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, he has seen firsthand how challenges related to poverty or income instability can affect a patient’s health.

“A reliable source of income could be the difference between having stable housing, or having regular access to food, or being able to afford prescribed medication,” he says. “Being able to afford these things can keep people out of the hospital.”

The substantial rise in the costs of the veterans disability compensation program has led some policymakers to suggest ways to reduce the amount of payments, Trivedi says.

“A major implication of our study is that we offer evidence that disability payments may reduce acute cure hospitalizations, among veterans, particularly those financed by Medicare,” he says. This not only benefits veterans’ health, but also makes financial sense. “So disability compensation may yield important reductions in public spending on medical care.”

Trivedi adds that this empirical evidence isn’t meant to justify disability compensation. “These payments are part of our country’s obligation to disabled veterans, and have been for hundreds of years,” he says. “What we’re trying to do is better understand the impacts of these payments for veterans.”

In addition to his roles at Brown’s School of Public Health and Warren Alpert Medical School, Trivedi is affiliated with the Center of Innovation in Long-term Services and Supports for Vulnerable Veterans at the Providence VA Medical Center. Study coauthors are from the VA Bedford Healthcare System; the University of Massachusetts, Lowell; Sai University in Chennai, India; and the United States Military Academy.

Support for the research came from the Health Services Research and Development Merit Award.

Source: Brown University