A new study identifies factors that hinder diabetes self-management among Haitian migrants working in sugar cane fields in the Dominican Republic.

The findings have implications for impoverished people struggling to self-manage their diabetes worldwide.

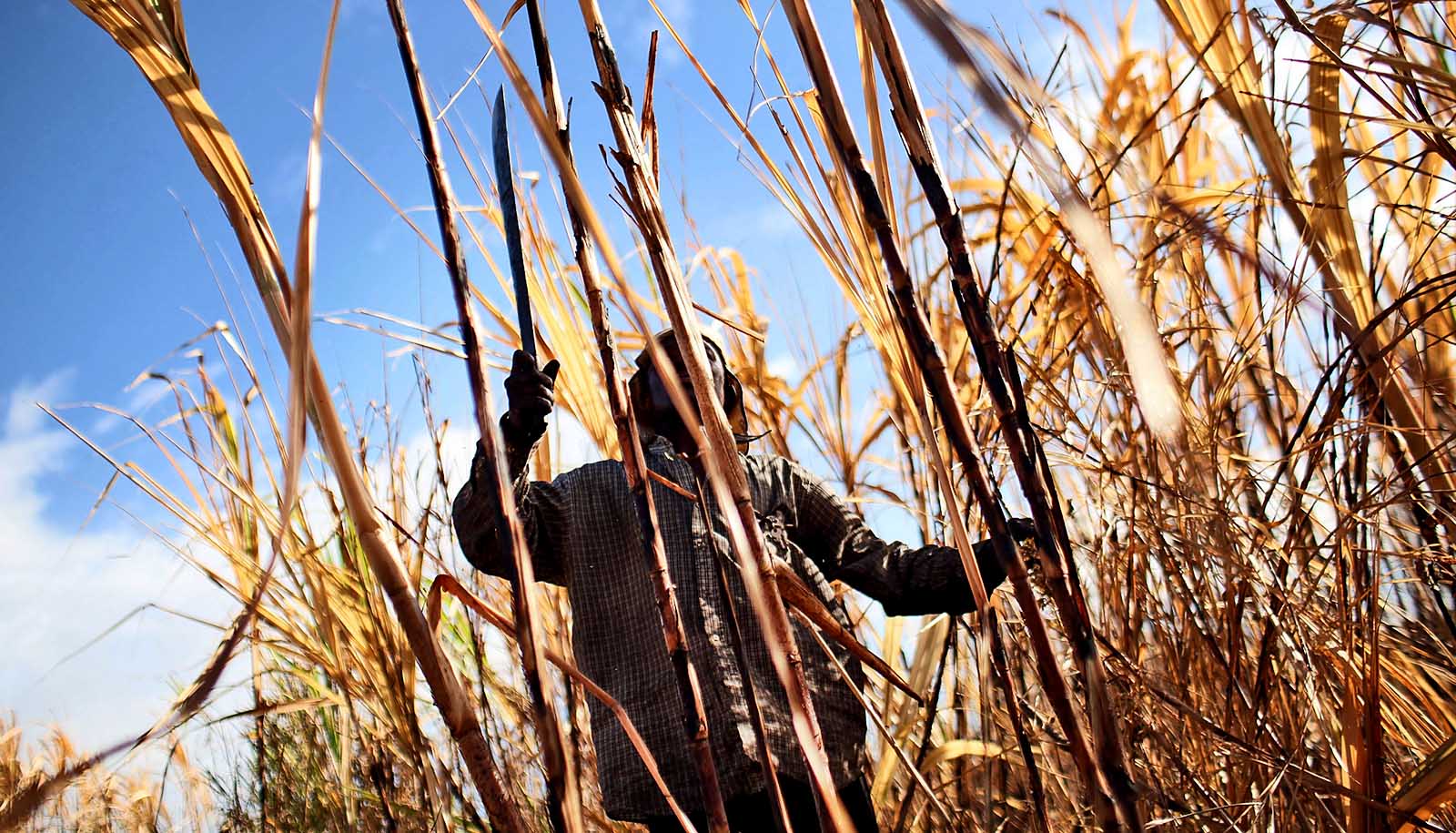

Rosalia Molina, a nurse who has taken previous medical missionary trips to the Dominican Republic to help impoverished individuals self-manage their diabetes, led the study as part of her doctoral studies at the University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing. She interviewed health care workers in the Dominican Republic about their challenges providing care to Haitian migrants working in “bateyes,” which are impoverished shanty-town camps on remote sugar cane fields.

“These workers have very little resources, as the bateyes often have no running water, electricity, or plumbing, and many of the individuals with diabetes have not been diagnosed or don’t know what to do to effectively self-manage their diabetes,” Molina says. “By first better understanding the compounding barriers that are limiting access to health care for these struggling individuals, we can develop more targeted interventions to help them survive as long as possible.”

While rice may be the primary source of food for these remote migrant workers, rice is a high-carb food, which may interfere with optimal blood sugar levels for those with diabetes. Through the interviews, Molina learned the impoverished migrants often see no other choice but to eat the high-carb food to avoid starvation.

Insulin is a common drug given to help individuals with diabetes regulate the amount of glucose in their blood. However, it requires proper refrigeration in order to be most effective, and the remote bateyes unfortunately have no refrigeration options available.

Through the interviews, Molina learned many of the migrants were more likely to trust their Haitian village priests who preach about Vodou, a traditional Afro-Haitian religion, rather than licensed medical professionals who may be unaware of the Haitians’ religious and cultural beliefs.

“For example, a common diabetes symptom is foot wounds, but the individuals may tell us they believe the foot wound was caused by witchcraft, so it speaks to the low health literacy rates as a potential barrier to self-management of diabetes,” Molina says.

Roads leading into the bateyes are often unpaved, and after heavy rainfall, the roads become so muddy that the remote bateyes become inaccessible for vehicles carrying health care professionals.

Molina adds that many of the migrant workers come to the Dominican Republic on a seasonal basis without the required work permits. Therefore, being undocumented leads many of these migrant workers with diabetes to avoid seeking medical help at hospitals to avoid the possibility of deportation.

While these challenges compound with each other to hinder access to health care for impoverished individuals, Molina says the findings can help inform possible solutions, such as planting community gardens in these remote areas to offer the workers alternative food sources, as well as working with Haitian village priests to incorporate health care education into their lectures.

“What is interesting is I am also active here in Missouri helping the Hispanic community—many of whom immigrated from Mexico and South America—with their diabetes self-management, and the challenges they face are often very similar to the challenges faced by the Haitians in the Dominican Republic,” says Molina, who immigrated to the United States from Mexico in 1995.

“It is important for the public to realize that diabetes is a very expensive and difficult disease for people to manage on their own, especially if they live in poverty, and I am passionate about trying to help.”

The study appears in the journal The Science of Diabetes Self-Management and Care. Funding came from The Research Foundation – Kansas City.

Source: University of Missouri