New research aims to tackle a significant problem: low levels of health literacy within the Deaf community.

The collaboration includes Tim Riker, a lecturer of American Sign Language at Brown University’s Center for Language Studies, clinicians and researchers, and group of Deaf community advisors who advise on how best to meet the needs of their peers.

“The objective is to understand the social, political, and historical experience of Deaf people and to transform health research in order to improve population health,” Riker says.

Members of the Deaf community, comprising about 500,000 individuals who communicate using American Sign Language, have historically experienced mistreatment in the research world, according to Riker and his colleagues.

“In the past, non-deaf people would lead research without the Deaf community being involved.”

The team conducted focus groups and community forums with Deaf people to collect information on how hearing researchers can do a better job of including Deaf people in biomedical research, says Melissa L. Anderson, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who led the collaboration. From there, they developed and tested a new research methodology, which they outline in a recent commentary in the journal Qualitative Health Research.

Cracking the code on effective qualitative research within the Deaf community could help address a range of health issues, Riker and Anderson say.

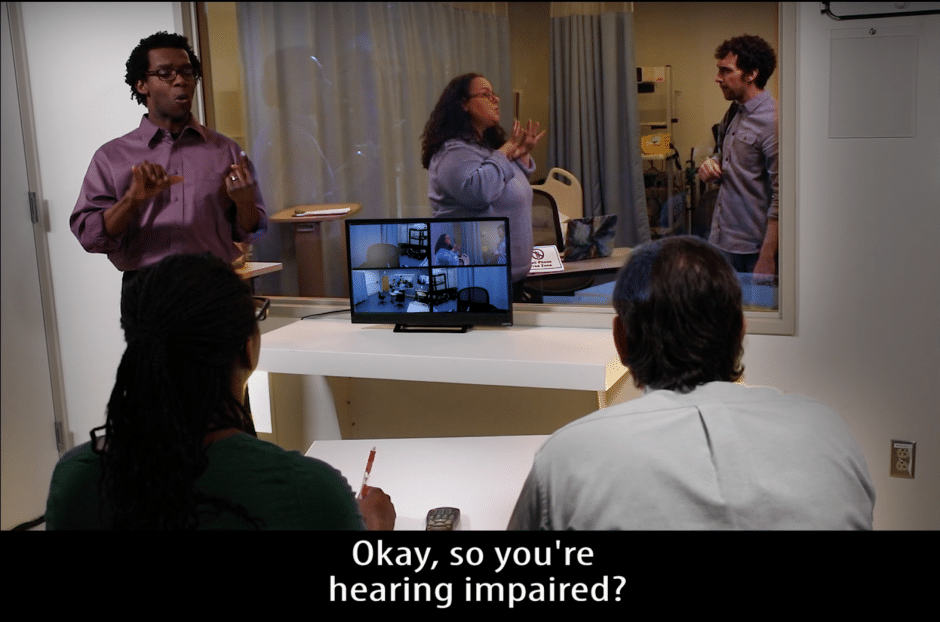

“What’s innovative about the research team’s method is we used technology to collect and analyze visual qualitative data directly in sign language,” Riker says. Traditionally those data have been translated into spoken English and transcribed into written English for analysis by hearing, non-signers.

“Mental illnesses, addiction, and trauma within the Deaf community are higher than among the general population,” Riker says. “Rates of obesity, diabetes, suicide, domestic violence, and sexual or intimate partner violence are also higher, along with other types of health disparities.”

Causes of health disparities

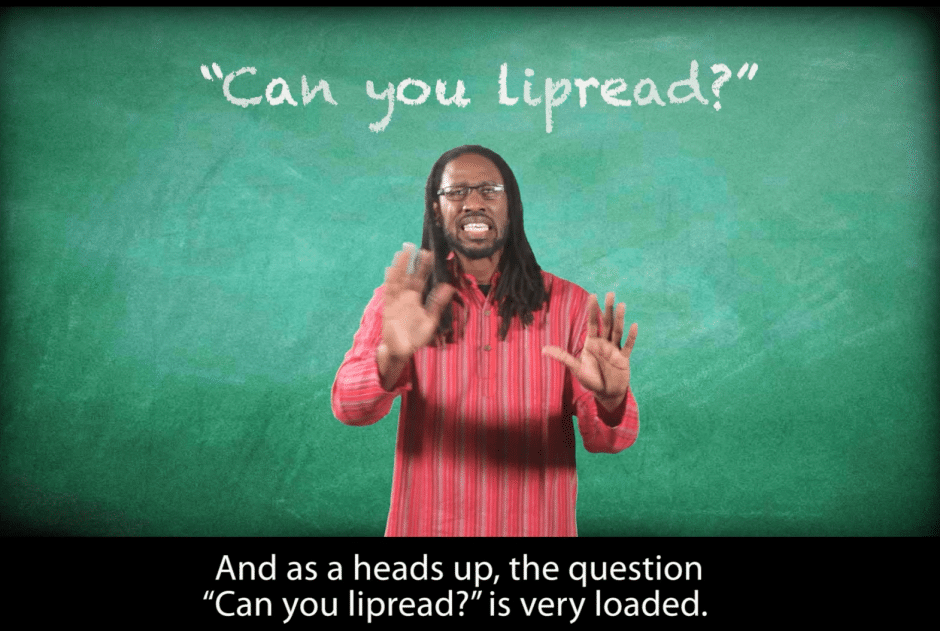

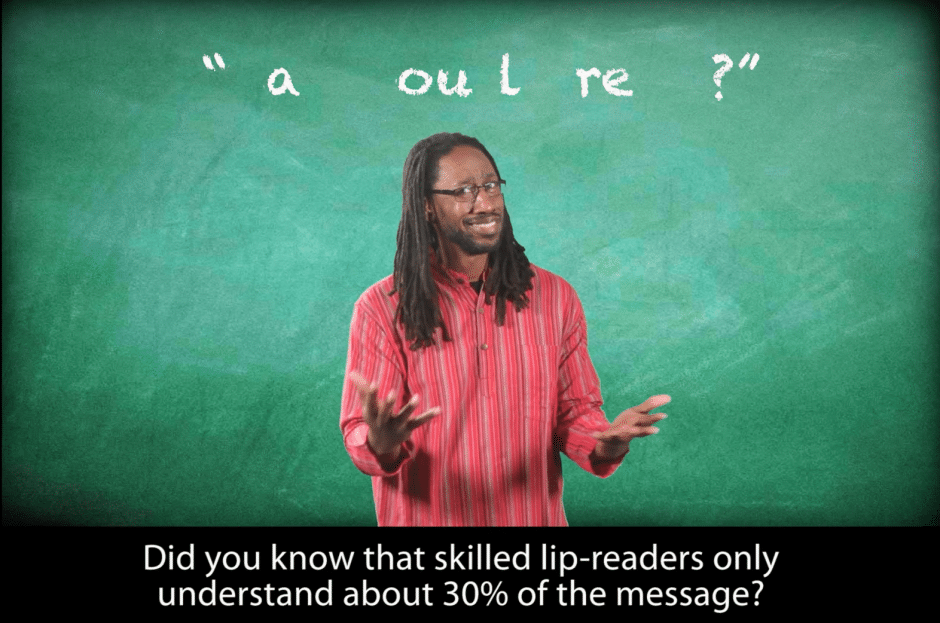

While reduced health literacy and its negative health outcomes arise in part from reduced incidental learning—for example, through overhearing and understanding conversations or spoken health information disseminated by radio or televised public service announcements—Deaf sign language users also often miss the chance to engage with health providers and health researchers, Riker says.

“As a hearing researcher within the Deaf community, I have to be aware of my limitations.”

Some methods of data collection, like telephone surveys, are inaccessible to some sign language users, and health researchers often do not include the interpreters and video technology necessary to interview Deaf subjects as they plan their research, Riker says.

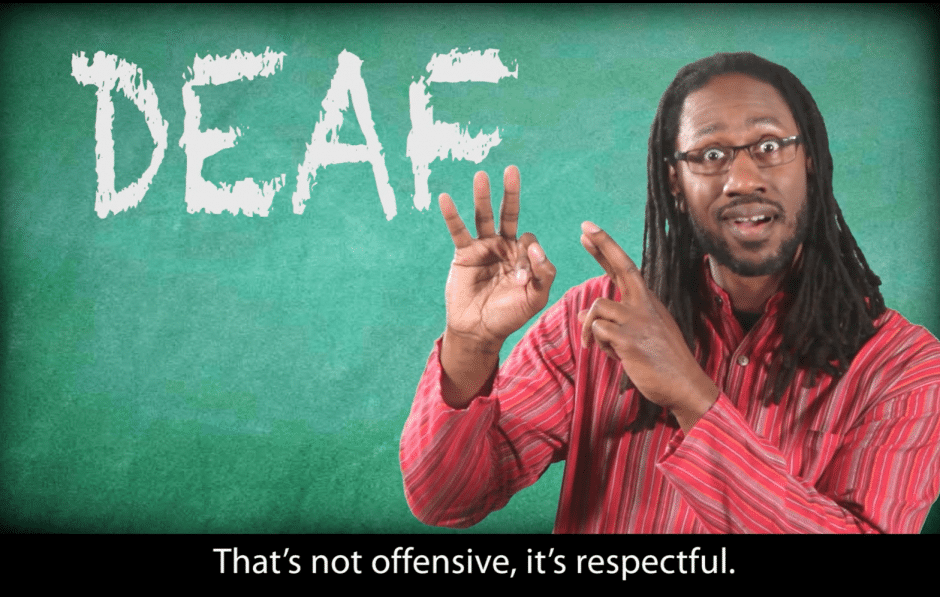

Written materials can also be problematic, according to Riker and his colleagues. Median English reading level among the Deaf population falls at approximately the fourth grade level. This is due, Riker says, to lack of resources and systemic failures related to early language acquisition and literacy. And ASL “is fully distinct from English—that is, it is not ‘English on the hands,'” the researchers write, but has its own structure and syntax. The move between ASL and English requires translation, not just transcription. When hearing researchers conduct such translations, they can be inaccurate or biased, the authors note.

Truth and reconciliation

“As a hearing researcher within the Deaf community, I have to be aware of my limitations,” Anderson says. “It’s always important to be partnering with people who truly understand Deaf experience to avoid pursuing research questions that are not important, not appropriate, or even offensive to Deaf people.”

Anderson, the principal investigator, cultivated a Deaf-majority research team. She and Riker began collaborating during the project’s grant-writing phase.

To engage the Deaf community, which has had negative experiences with biomedical researchers, according to Riker, the group used the truth and reconciliation model—a form of fact-finding perhaps best known for its use in post-Apartheid South Africa.

“We use the model to help to heal, to come together collaboratively and to make suggestions and recommendations,” Riker says. “The Deaf community was part of the research from the beginning. In the past, non-deaf people would lead research without the Deaf community being involved. This is a more integrative type of research and an even exchange.”

Jeroan Allison, a professor quantitative health sciences at the UMass Medical School, has used the truth and reconciliation model to engage underserved black and Latinx communities in biomedical research with good results, Anderson says: “We applied that same process of listening to the transgressions of the majority world, apologizing, and trying to move forward together.”

Tips for researchers

The researchers recommend reforming research practice in the following ways:

- Cultivate a Deaf-majority research team to provide cultural and linguistic expertise as well as input on study design, interpretation, and strategies for disseminating findings to the Deaf community.

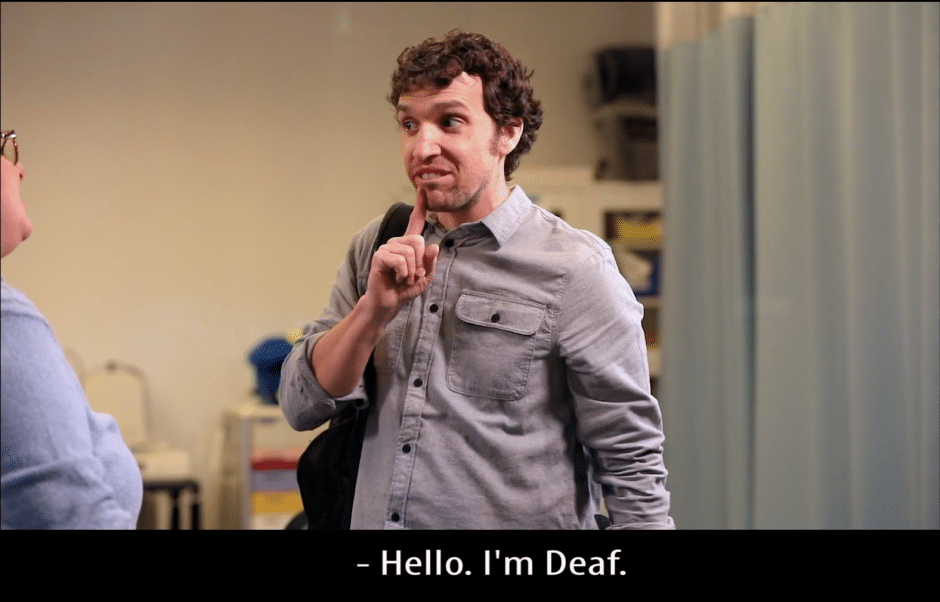

- Collect data directly in the primary language of the participants (ASL) using a sign-only environment.

- Use multiple video streams to fully capture expression, including facial expressions, which can affect the meaning of an utterance.

- Upload video data into a qualitative analysis software package for coding without first transcribing it. This allows the researchers to code both linguistic and nonlinguistic data that a text translation would miss.

- Analyze data collaboratively to interpret the meaning of Deaf participants’ statements without personal or cultural biases.

- Disseminate findings back to key Deaf stakeholders and the lay community through open-access products and ASL research briefs.

- In disseminating findings to the scientific community, translate only salient direct quotes, rather than the entire dataset, into English, with the guidance of community advisors who serve as linguistic experts and cultural brokers. This preserves data in its original form, rather than as a body of translated material.

The research team created a 40-minute training video that demonstrates how to interact with Deaf research participants, specifically during the informed-consent process.

Sign language in Philly has an ‘accent’

While the focus of the team’s work was research in the Deaf community, the methodology can also apply to research in the 3,233 living language languages that do not have a standardized writing system, including over 138 documented sign languages, the authors note.

Source: Brown University