The US is still on its heels when it comes to COVID-19 testing. Will mailing free at-home tests make a difference? An immunologist has some answers.

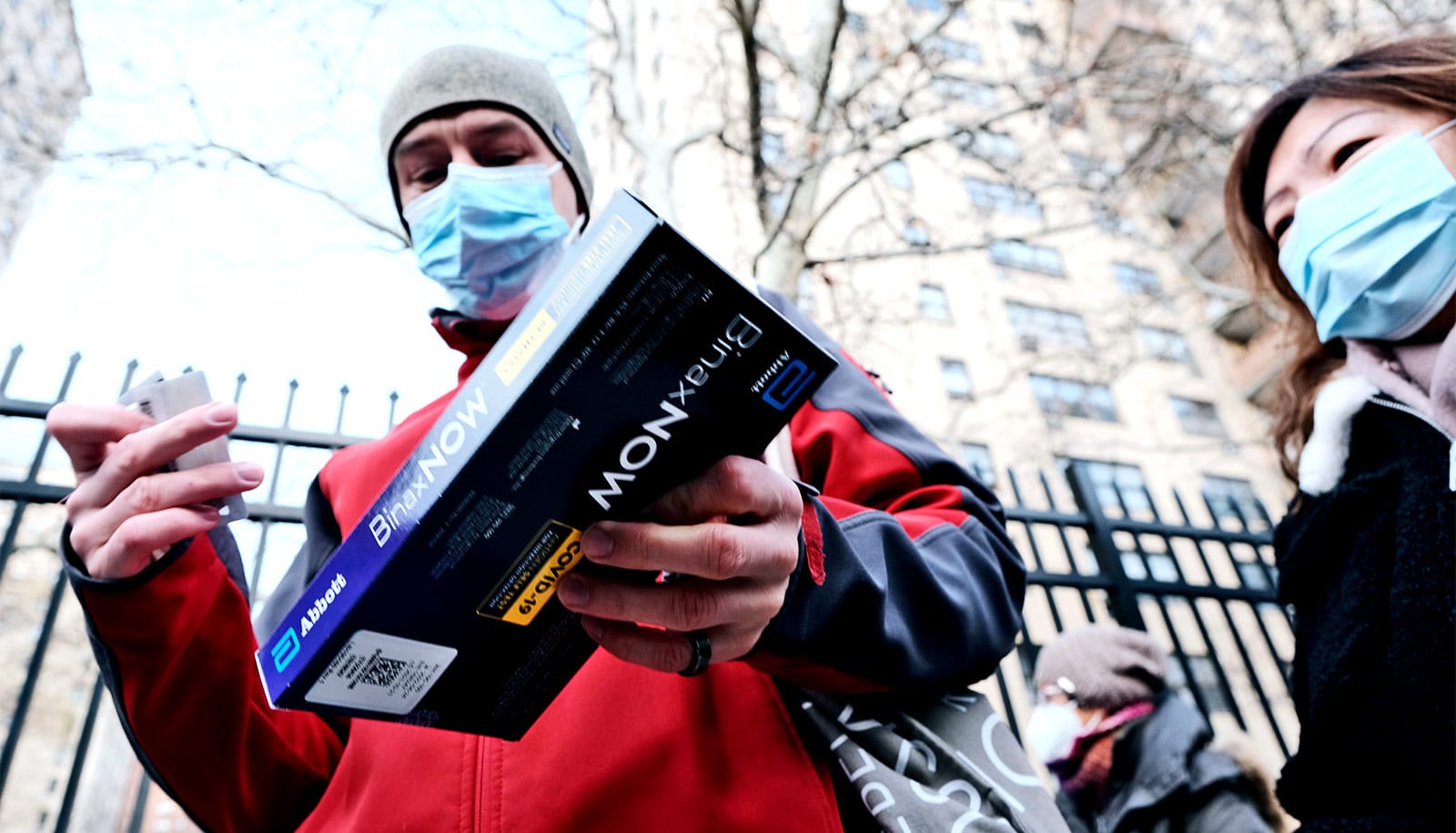

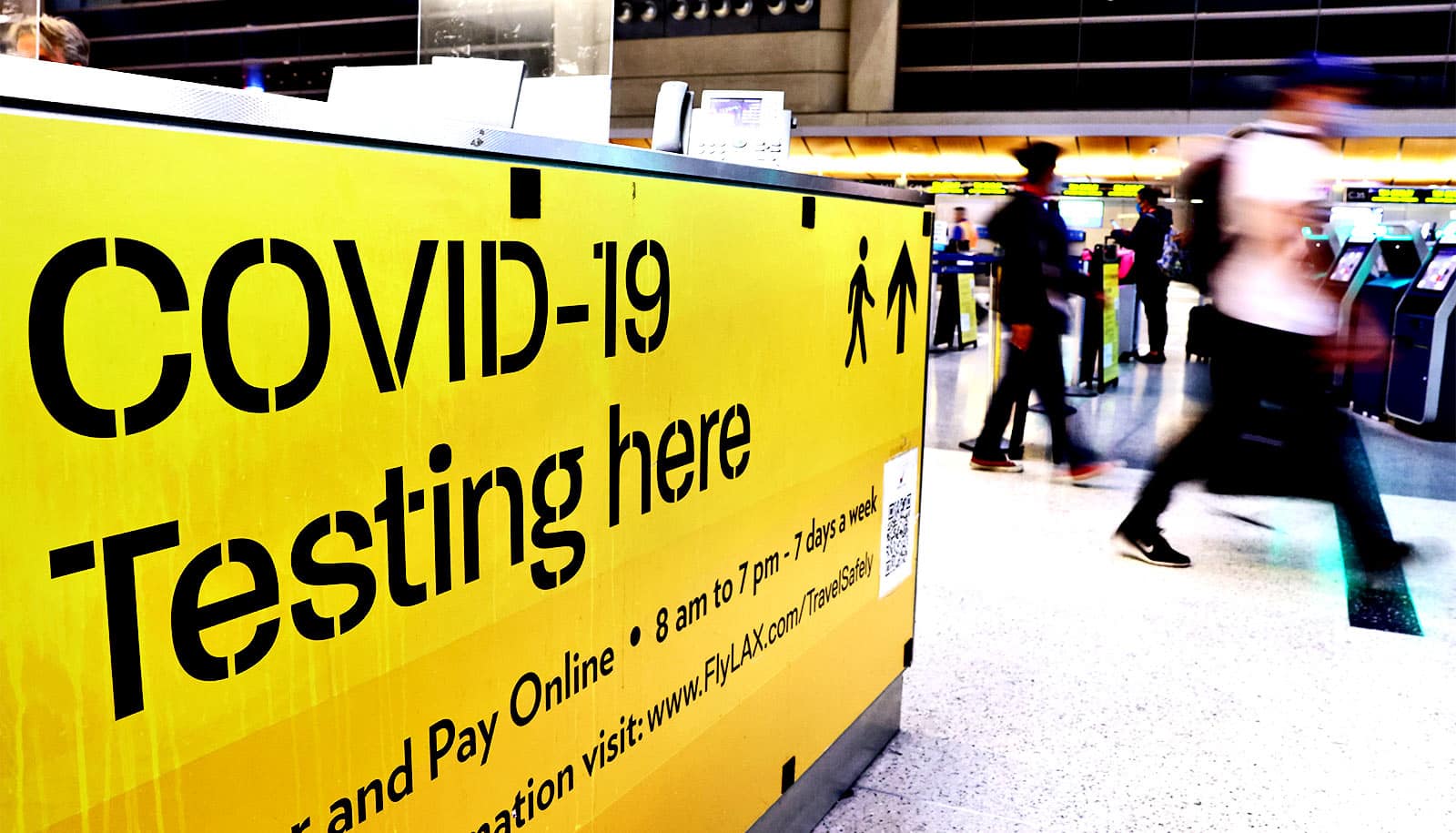

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve heard that frequent testing should be a key component in controlling spread of COVID-19. The Biden Administration has announced plans to mail half a billion free COVID-19 tests to people who request them online, in addition to opening a number of new testing sites across the country. The administration has also been exploring a proposal to offer Americans free at-home tests with reimbursement from their private insurance companies.

During the pandemic, Gigi Gronvall, associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and senior scholar at the Center for Health Security, has led that center’s efforts to track development and marketing of COVID-19 tests as well as national testing strategies.

Here, she offers a pulse check on the current state of COVID-19 testing in the US, what could improve the situation, and what’s next:

What’s your impression of the state of COVID testing in the US right now?

It seems that the problems in testing right now are very localized, but given that cases are rising, and will continue to rise with Omicron, it’s just going to get worse. Even areas that are doing well right now will feel the strain.

One of the biggest issues throughout the pandemic with the PCR tests [typically administered at drugstores and health centers] has been the lagging time to get results. Sometimes it can take something like 72 hours or more, and at that point it’s not useful as a tool for limiting case numbers or if you need to have proof of a negative test to get on a flight, you’re out of luck.

With the self-administered rapid tests, the problem has been availability. The rapid tests can be a wonderful tool for people to make decisions about how to spend their days, who they visit, and distinguishing COVID from a common cold or other illness. But unfortunately in the US, we’ve let the market influence availability. When we had some relief before the Delta variant hit, there wasn’t much demand for tests and manufacturing slowed down accordingly. But then Delta came and we weren’t ready. It seems that the same happened with Omicron. But the measures announced by President Biden to ramp up our responses to COVID-19—including testing, support for hospitals, more vaccinators—are very welcome and should make a difference. The president didn’t mention improving air quality, but that is another very important mitigation measure—people should know that they can do more to purify the air in their homes, businesses, and schools to reduce risks.

In the US, a lot of the effort and push has focused primarily on vaccinations, which is critical, but as we can see, it’s not going to be enough.

How do you think the situation could be improved?

I do want to point out that there’s a lot of criticism over the way the pandemic is being handled, but we shouldn’t be so quick to throw people who are working very hard under the bus. Because this has been relentless—months and months and months of working harder than ever before.

In Maryland right now, for example, we’re dealing with [the aftermath of] a ransomware attack that impeded accurate data for some time. So we’re dealing with multiple crises piling on top of each other and an exhausted workforce, and we have to be sympathetic to conditions that keep changing. We have to fix this so that public health and health care are more resilient in the future.

But testing is an area that we can at least look at and know for sure that we can do better, and we have an idea of how to do that. A lot of other aspects of the pandemic are more slippery and elusive, but this one is concrete. We understand what we’re dealing with and we know that this is an important tool for limiting spread.

Do you think the Biden administration’s idea to reimburse the cost of at-home rapid tests is a step in the right direction?

It’s a good idea that people won’t have to pay for the tests and that insurance can cover the costs. But think of it like any consumer product. If someone’s looking for a new camera, and there’s a $100 mail-in rebate, that can sound great initially but a lot of people are going to forget about the rebate, or lose it, or for whatever reason not reach that step.

With the COVID tests, we can assume a lot of people are going to do the same. They won’t take the steps to file for reimbursement. Nobody likes dealing with insurance companies, right? If it’s for $1,000 medical bill, they’d go through the hassle, but probably not the case for a much less expensive COVID test. So whenever you put up barriers like that to access, it’s inevitably going to create problems.

At this point, we’re seeing more action on the state level with programs to deliver free tests in large quantities. Massachusetts is one of the latest examples of that. The Baltimore City Health Department teamed up with the Enoch Pratt Library system to provide free tests, though they ran out of tests almost immediately. Perhaps Omicron will force this issue on a wider scale in other cities and states.

With the rapid tests, one concern is that people aren’t reporting their results, so our data on trends are always going to be incomplete. What are your thoughts on that?

That’s always going to be an issue when it comes with home-based tests for any kind of disease. It’s true that you’re not going to get the same kind of accurate data you would if the tests were going through a central authority. And the loss of data is definitely a downside. But personally I think the value of being able to test—and to use that to make decisions—outweighs the loss you get in the data. Nothing can be perfect.

We can get information about case numbers in various ways, and we know that we’ll never be able to capture all of them, but just the value of being able to quickly find out if you have COVID can really make a difference in limiting infections. For example, if you know your child was exposed and you can test them quickly without dragging them out to get a test and wait days for results.

With Omicron spreading, how do you think people should be thinking about testing?

One, I think there could be some value in expanding testing programs that are now focused on unvaccinated people. For example, a lot of schools or companies have policies requiring that people can either be vaccinated or they get tested weekly. Maybe the weekly tests now need to extend to vaccinated people.

Of course we’re still learning about Omicron, but people should know that the data at this time suggest there will be shorter incubation periods for the virus. So if you’re using tests, for example, to clear yourself before visiting someone or joining a gathering, you should reduce the interval between testing and doing that activity.

With Delta, it was suggested that it was OK to test two or three days before the activity, but now it is a better idea to test the day of or even better, right before gathering. We’ll have to watch the data.

Source: Johns Hopkins University