Chemical and isotopic analysis of copper artifacts from southern Africa reveals new cultural connections among people living in the region between the 5th and 20th centuries, according to a new study.

People in the area between northern South Africa and the Copperbelt region in central Africa were more connected to one another than scholars previously thought, says Jay Stephens, a postdoctoral fellow in the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR) Archaeometry Lab.

“Over the past 20 to 30 years, most archaeologists have framed the archaeological record of southern Africa in a global way with a major focus on its connection to imports coming from the Indian Ocean,” he says.

“But it’s also important to recognize the interconnected relationships that existed among the many groups of people living in southern Africa. The data shows the interaction between these groups not only involved the movement of goods, but also flows of information and the sharing of technological practices that come with that exchange.”

Clues from copper ingots

For years, scholars debated whether these copper artifacts, called rectangular, fishtail, and croisette copper ingots, were made exclusively from copper ore mined in the Copperbelt region or from Zimbabwe’s Magondi Belt. As it turns out, both theories are correct, Stephens says.

“We now have tangible linkages to reconstruct connectivity at various points in time in the archeological record,” he says. “There is a massive history of interconnectivity found throughout the region in areas now known as the countries of Zambia, Zimbabwe, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This also includes people from the contemporary Ingombe Ilede, Harare, and Musengezi traditions of northern Zimbabwe between at least the 14th and 18th centuries AD.”

To determine their findings, researchers took small samples from 33 copper ingots and analyzed them at the University of Arizona. The researchers carefully selected all samples from archeological samples found in the collections of the Museum of Human Sciences in Harare, Zimbabwe, and the Livingstone Museum in Livingstone, Zambia.

“We didn’t want to impact the display of an object, so we tried to be aware of how museums and institutions would want to interact with the data we collected and share it with the general public,” Stephens says. “We also want our knowledge to be accessible for the individuals in these communities who continue to interact with these objects. Hopefully, some of the skills linked with these analyses can be used by whomever wants to ask similar questions in the future.”

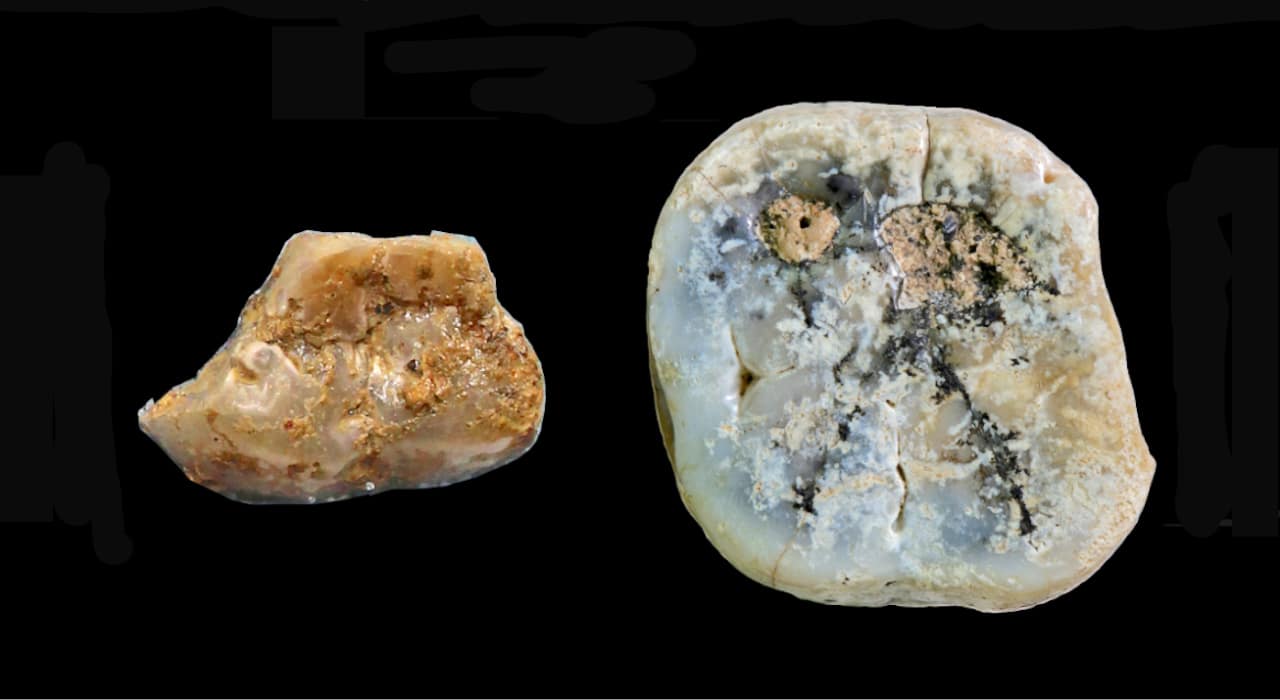

Copper ingots are excellent objects for this type of analysis because they often have emblematic shapes that allow archaeologists to identify specific markings and follow changes over different time periods, Stephens says.

“By looking at their changes in shape and morphology over time, we can pair those changes with how technology changed over time,” he says. “This often comes from observing the decorative features produced from the cast object or mold, or other surface attributes found on these objects.”

Lost history

Once the samples arrived at the University of Arizona lab, researchers took a small amount of each sample—less than one gram—and dissolved it with specific acids to leave behind a liquid mixture of chemical ions. Then they analyzed the samples for lead isotopes and other chemical elements. One challenge the team encountered was a lack of existing data to match their samples with.

“One part of the project included analyzing hundreds of ore samples from different geological deposits in southern Africa—especially ones mined before the arrival of European colonial forces—to create a robust data set,” Stephens says. “The data can provide a scientific foundation to help back up the inferences and conclusions we make in the study.”

Stephens says the data they collect is one of the only remaining tangible links that exist today to those precolonial mines in Africa.

“Unfortunately, large open pit mines have destroyed a lot of the archaeological sites and broader cultural landscapes around these geological deposits,” he says. “This makes it a challenge to reconstruct the history related to these mines. It’s a concerning development, especially with the global push toward more electric vehicles which use minerals like copper and cobalt found in the Copperbelt.”

The study appears in PLOS ONE. Additional coauthors are from the University of Arizona, the University of Oxford, the University of Cape Town, and the University of Missouri.

The National Science Foundation supported the work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri