Instead of turning up the thermostat, high-tech, flexible patches sewn into your clothes may one day keep you warm and significantly reduce your electric bill and carbon footprint at the same time.

Engineers have discovered a way to use intense pulses of light to fuse tiny silver wires with polyester to make thin, durable heating patches. Their heating performance is nearly 70 percent higher than similar patches, according to a new study, which appears in Scientific Reports.

They are inexpensive, can get power via coin batteries, and are able to generate heat where the human body needs it since they can be sewn onto clothing.

Wasted energy

“This is important in the built environment, where we waste lots of energy by heating buildings—instead of selectively heating the human body,” says senior author Rajiv Malhotra, an assistant professor in the mechanical and aerospace engineering department at Rutgers University–New Brunswick.

It is estimated that 47 percent of global energy is used for indoor heating, and 42 percent of that energy is wasted to heat empty space and objects instead of people. Solving the global energy crisis—a major contributor to global warming—would require a sharp reduction in energy for indoor heating.

Personal thermal management, which focuses on heating the human body as needed, is an emerging potential solution. Such patches may also someday help warm anyone who works or plays outdoors.

Smart fabrics

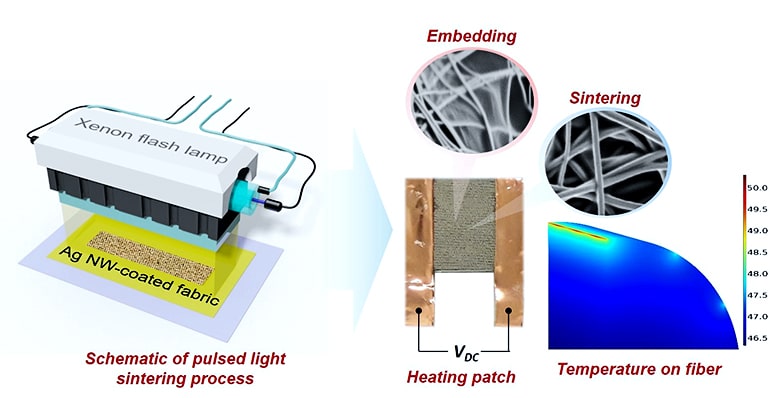

To create the patches, engineers used “intense pulsed-light sintering” to fuse silver nanowires to polyester fibers. The nanowires are thousands of times thinner than a human hair. The process only takes 300 millionths of a second.

When compared with the current state-of-the-art thermal patches, the new creation generates more heat per patch area and is more durable after bending, washing, and exposure to humidity and high temperature.

The next step is to see if the new method can be used to create other smart fabrics, including patch-based sensors and circuits. The engineers also want to find out how many patches are needed and the best placement to keep users comfortable while reducing indoor energy consumption.

Additional researchers are from Rutgers and Oregon State University. The National Science Foundation and Walmart US Manufacturing Innovation Fund supported the work.

Source: Rutgers University