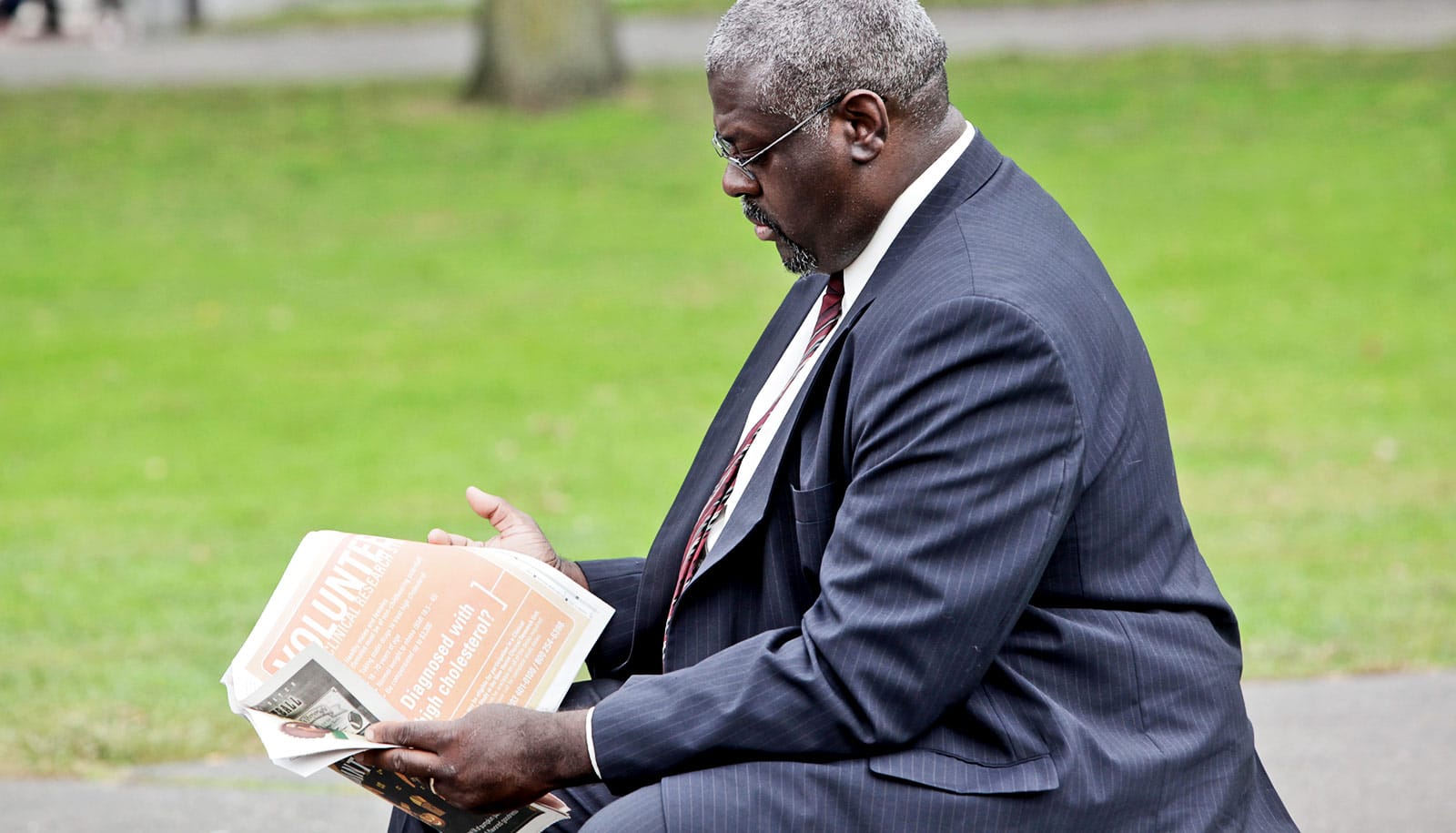

Black men who attend church almost daily are nearly three times more likely to have obesity than those who never (or very rarely) attend, a new study shows.

Moreover, the study found health differences across denominations: Among black Americans, Catholics and Presbyterians had lower odds of diabetes than Baptists.

The obesity epidemic, like many deleterious outcomes in America, has disproportionately affected the black population, researchers say. While nearly one-third of all men and women have obesity, the rate jumps to nearly one-half (48.4%) among African Americans, putting them at greater risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Previous studies have noted a connection between religious attendance and obesity. However, the new report in the Journal of Religion and Health explores that relationship with a specific lens on black Americans who, based on a 2014 study from Pew Research Center, are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to believe in God, consider religion important, attend church frequently, and read prayer and scripture.

Self care and faith

“Historically black churches have been a source of spiritual and social support, but greater religious engagement must also support good health behaviors,” says lead author Keisha L. Bentley-Edwards, assistant professor of general internal medicine, associate director of research, and director of the health equity working group at the Cook Center at Duke University.

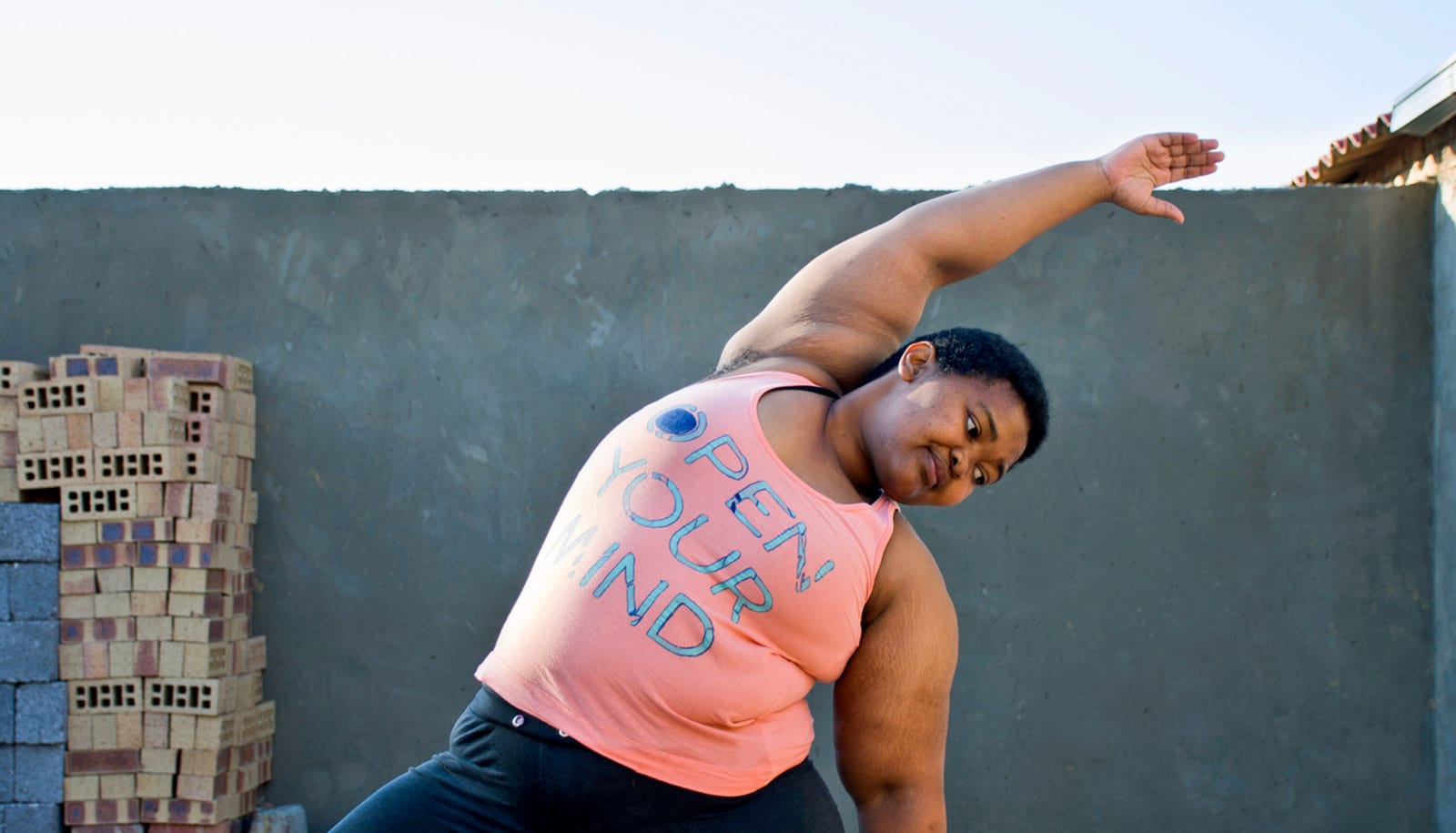

“Both men and women who are active members of their churches are being pulled in a lot of directions outside of their faith community, which can make self-care a lower priority than what is warranted. We want them to make faith and health priorities in their lives, rather than faith or health.”

Researchers used data from the National Survey of American Life to study the intertwining of faith behaviors and health outcomes for more than 4,300 African American and Afro-Caribbean Christians.

The findings show that black men who attend services “nearly every day”—the shortest interval tracked—were roughly three times as likely to have obesity than those never attending or attending less than once a year.

Detecting the reason for this high obesity rate—and, specifically, the negative relationship that exists for men but not women—will require further inquiry, the authors say.

Denominational differences

Researchers have begun to understand how obesity can spread through social networks. For those frequenting the church, the authors write, the space “may facilitate the transfer of obesity” through shared social norms.

The authors also built upon prior research that showed, when considering multiple races across Christian denominations and other faiths, obesity is most prevalent among Baptists. While the authors note no faith-based disparities in obesity rates in their study of black Christians, they found Baptists are significantly more likely to have diabetes than either Presbyterians or Catholics.

The researchers hope that future studies comparing other diabetes risk factors will help explain the increased prevalence of the disease among Baptists. They also posit that denominational differences in attitudes towards one’s body—for example whether one considers the body “a vessel through which members serve God”—may drive these results.

Above all, the researchers suggest the importance for greater finesse in religious health interventions, including the need to potentially tailor these strategies through faith, rather than a uniform approach.

“Although researchers and practitioners have used historically black churches as sites for health promotion initiatives, the nuances within and between denominations are often lost, which may impact the effectiveness of their programs,” Bentley-Edwards says. “We need novel understandings of the indicators that protect and diminish health outcomes.”

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities funded the work.

Source: Duke University