Specialized immune cells called macrophages can trigger intestinal contractions, independent of the nervous system, that lead to the diarrhea so many cancer patients develop as a result of chemotherapy, according to new research in mice.

Some 50 to 80 percent of cancer patients taking powerful chemotherapy drugs develop diarrhea, which can be severe and in some cases life-threatening.

Their problems occur when contractions in the smooth muscle lining the gastrointestinal (GI) tract go haywire as food is digested. The same issues can occur in people with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease.

For decades, scientists have thought the contraction problems originated with nerve cells in the intestines. The new research, however, provides a new target to help treat chemotherapy-induced diarrhea and, potentially, diarrhea linked to other GI problems.

The findings also raise the possibility that drugs developed to treat diarrheal-related intestinal disorders may have targeted the wrong cells, which could help explain why treatments for these conditions often aren’t very effective.

“Diarrhea is a common side effect of chemotherapy that, in severe cases, can lead to death or to patients having to stop lifesaving treatment because often there are no effective therapies to control the diarrhea,” says co-senior investigator Hongzhen Hu, an associate professor of anesthesiology at Washington University in St. Louis. “This research provides a new avenue to explore in developing drugs to stop such diarrhea.”

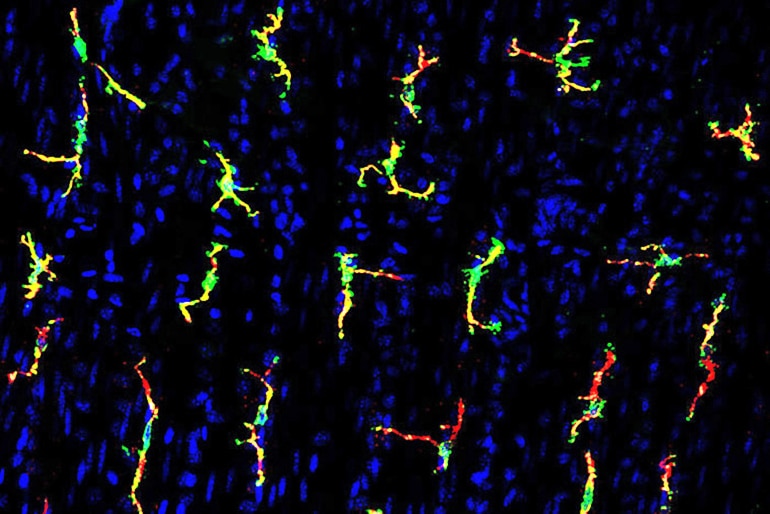

Macrophages are known for their role in fighting infections, cancer, and inflammation. Although the largest population of macrophages in the body resides in the gut, scientists have not understood what some of those cells were doing to help keep the GI tract healthy.

The researchers focused on a receptor on macrophages called TRPV4. These receptors are important to contractions in the gut but had been assumed to be located on nerve cells.

“We found that the macrophages themselves trigger muscle contractions in the gut without any involvement from neurons,” says Hu. “The pathway works in an entirely different way from what we had expected.”

Previously, Hu and colleagues had identified a role for macrophages’ TRPV4 receptors in chronic itching in the skin. Here, they focused on macrophages that reside in the gut’s smooth muscle layer, demonstrating that the receptors sense heat, chemical changes, and the movement of food through the intestine. All of those things can trigger muscle contractions, or motility, in the gut.

Breast cancer patients need more support for ‘chemo brain’

In experiments involving genetically modified mice, the researchers found that animals without TRPV4 receptors on gut macrophages had poor intestinal motility. They also found that by inhibiting the actions of these receptors, they could reverse the diarrhea chemotherapy drugs caused.

“Solving problems with bowel function in chemotherapy patients is important because at least half of those patients develop diarrhea, but we’d also like to see whether these receptors on macrophages can be targeted to treat irritable bowel syndrome, which often doesn’t respond well to existing drugs,” Kim says.

The research appears in Immunity.

Grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) supported the research.