Every year throughout its 4.5-billion-year life, ice volcanoes on the dwarf planet Ceres generate enough material to fill a movie theater—13,000 cubic yards, according to a new study.

The study marks the first time researchers have calculated a rate of cryovolcanic activity from observations—and the findings help solve a mystery about Ceres’ missing mountains, researchers say.

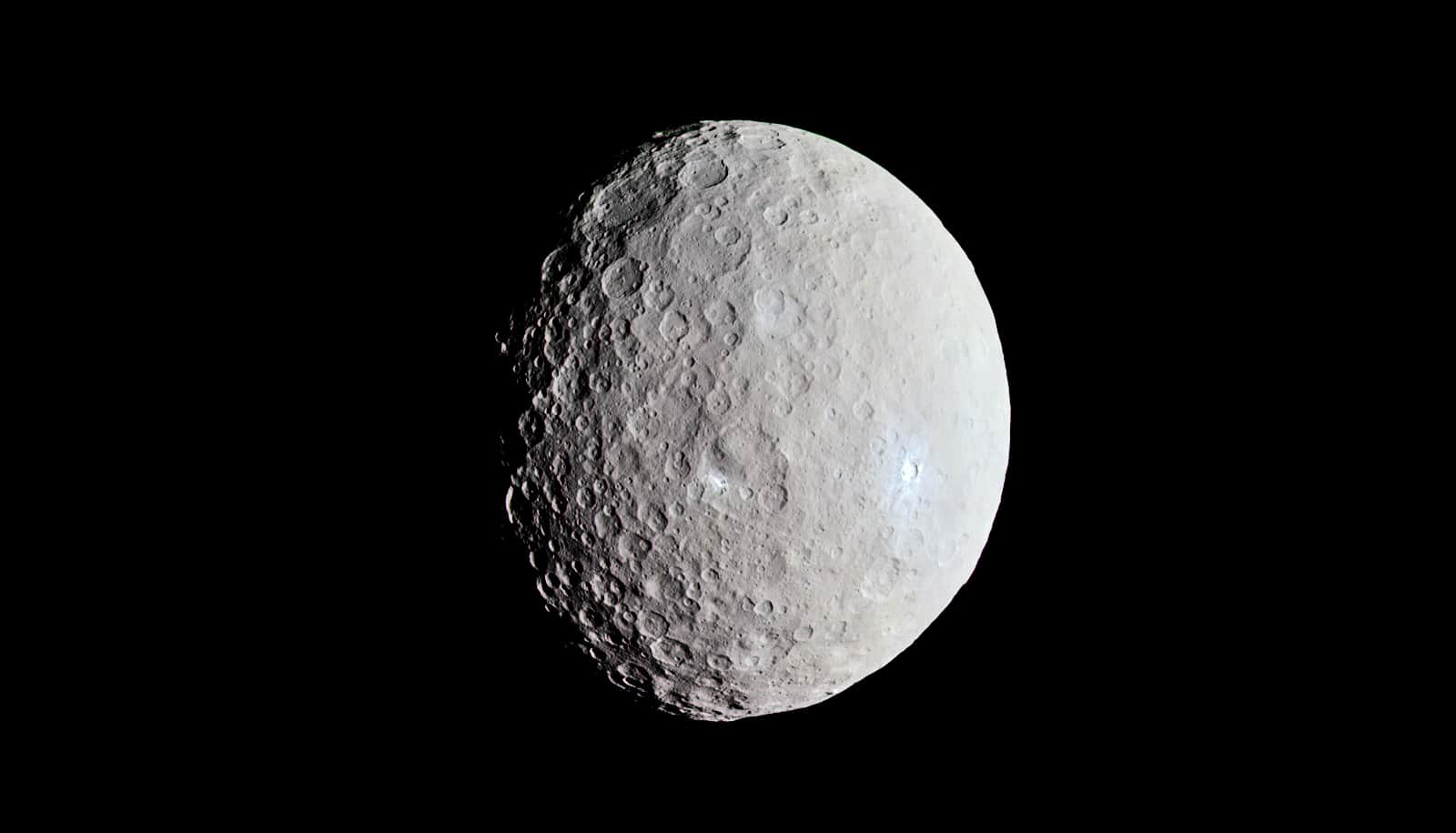

Discovered in 2015 by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, the 3-mile-tall ice volcano Ahuna Mons rises over the surface of Ceres. Still geologically young, the mountain is at most 200 million years old, meaning that—though it is no longer erupting—it was active in the recent past.

Is Ahuna Mons a loner?

Ahuna Mons’ youth and loneliness presented a mystery. It seemed unlikely Ceres laid dormant for eons and suddenly erupted in one place. But if other ice volcanoes had risen out of the Cerean surface in ages past, where are they now? Why is Ahuna Mons so alone?

Researchers set out to answer these questions. They report their findings in Nature Astronomy.

In an earlier paper the researchers published last year, they theorized that a natural process called “viscous relaxation” erased evidence of older volcanoes on the dwarf planet. Viscous materials, like honey or putty, can begin as a thick blob, but the weight of the blob causes it to ooze into a flatter shape over time.

“Rocks don’t do that under normal temperatures and timescales, but ice does,” says Michael Sori, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona.

Because Ceres is made of both rock and ice, Sori pursued the theory that formations on the dwarf planet flow and move under their own weight, similar to how glaciers move on Earth. The formations’ composition and temperature would affect how quickly they relax into the surrounding landscape. The more ice in a formation, the faster it flows; the lower the temperature, the slower it flows.

Though Ceres never grows warmer than -30 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature varies across its surface.

“Ceres’ poles are cold enough that if you start with a mountain of ice, it doesn’t relax,” Sori says. “But the equator is warm enough that a mountain of ice might relax over geological timescales.”

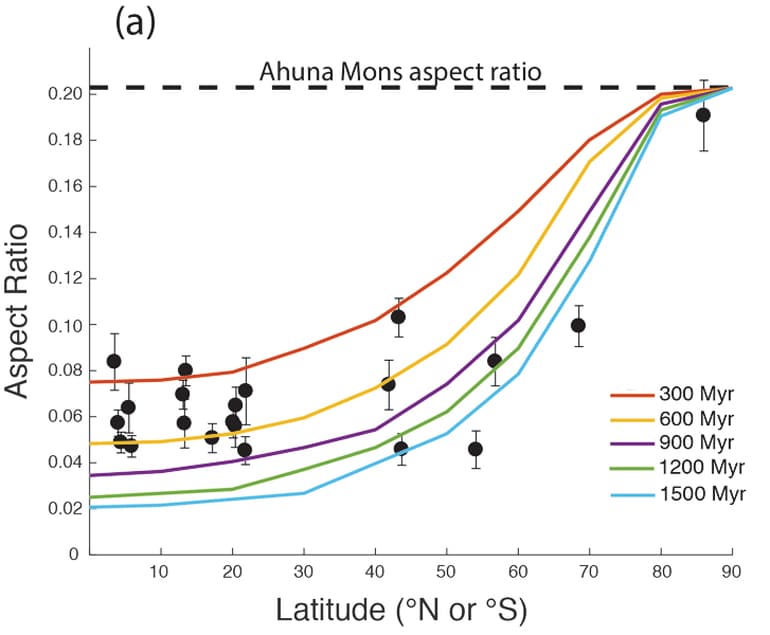

Computer simulations showed that Sori’s theory was viable. Model cryovolcanoes at the poles of Ceres remained frozen in place for eternity. At other latitudes on the dwarf planet, model volcanoes began life tall and steep, but grew shorter, wider, and more rounded as time passed.

To prove the computer simulations had played out in reality, Sori scoured topographic observations from the Dawn spacecraft, which has been orbiting Ceres since 2015, to find landforms that matched the models.

Across the 1 million square miles of Cerean surface, Sori and his team found 22 mountains including Ahuna Mons that looked exactly like the simulation’s predictions.

“The really exciting part that made us think this might be real is that we found only one mountain at the pole,” Sori says.

1 volcano every 50 million years

Though it is old and battered by impacts, the polar mountain, dubbed Yamor Mons, has the same overall shape as Ahuna Mons. It is five times wider than it is tall, giving it an aspect ratio of 0.2. Mountains found elsewhere on Ceres have lower aspect ratios, just as the models predicted: they are much wider than they are tall.

By matching the real mountains to the model mountains, Sori was able to determine the age of many of them. Researchers studied the volcanoes’ topography to estimate their volume, and by combining age and volume, Sori’s team was able to calculate the rate at which cryovolcanoes form on Ceres.

“We found that one volcano forms every 50 million years,” Sori said.

This amounts to an average of more than 13,000 cubic yards of cryovolcanic material each year—enough to fill a movie theater or four Olympic-sized swimming pools. This is much less volcanic activity than what is seen on Earth, where rocky volcanoes generate more than 1 billion cubic yards of material in a year.

In addition to being less productive, volcanic eruptions on Ceres are tamer than those on Earth. Instead of explosive eruptions, cryovolcanoes create the icy equivalent of a lava dome: the cryomagma—a salty mix of rocks, ice, and other volatiles such as ammonia—oozes out of the volcano and freezes on the surface. Most of the once-mighty cryovolcanoes on Ceres likely formed this way before they relaxed away.

The causes of cryovolcanic eruptions on Ceres are still a mystery, but future research might yield answers, as signs of ice volcanoes have been spotted on other bodies in the solar system as probes have flown by.

Ceres is the first cryovolcanic body a mission has orbited, but Europa and Enceladus, moons of Jupiter and Saturn, are likely candidates for cryovolcanism, as are Pluto and its moon Charon. Europa is of special interest because researchers believe it has liquid oceans trapped below a thick icy shell, which some believe may be dotted with ice volcanoes.

“There might be similarities between Europa and Ceres, but we need to send the next mission there before we can say for sure,” Sori says.

NASA’s Dawn Guest Investigator Program funded the work.

Source: University of Arizona