Collective cell movement, such as metastasizing cancer cells or wound healing, requires coordinated actions. But cells are most effective at communication when they’re not tightly packed together, research shows.

This was a surprise, says Andrew Mugler, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Purdue University who studies cell behavior.

“Our hypothesis was proven wrong,” Mugler says. “Our hypothesis was that cells that are closer to each other should experience a sensory improvement. Instead, we found that long-range communication was better, even though it meant that cells had to be receiving weaker communication signals.”

“Long range” is a relative term when studying life at the microscopic level, but Mugler says the optimal range for small groups of cells, up to about 200 cells, was five cell diameters. For more than 1,000 cells the optimal range was more like 10-15 cell diameters.

How Stone Age travel could clarify metastatic cancer

Cells communicate in one of two ways: either by excreting messenger molecules, or by directly exchanging small molecules when closer together.

It turns out that the more direct method becomes less effective because a “telephone game” effect comes into play. But also, Mugler says, the more dispersed cells provide each other with a more accurate view of their environment.

“It would be as if you and I both had thermometers and wanted to measure the outdoor temperature,” he says. “If we are standing right next to each other but we are both in the direct sunlight or in deep shade, we might not get an accurate reading.

“But if we’re 50 feet apart, we can still communicate, but together we’re more likely to measure an accurate temperature. The same effect happens at the cellular level.”

Mugler says learning more about how cells communicate and organize will be important to gain a better understanding of many areas of medicine.

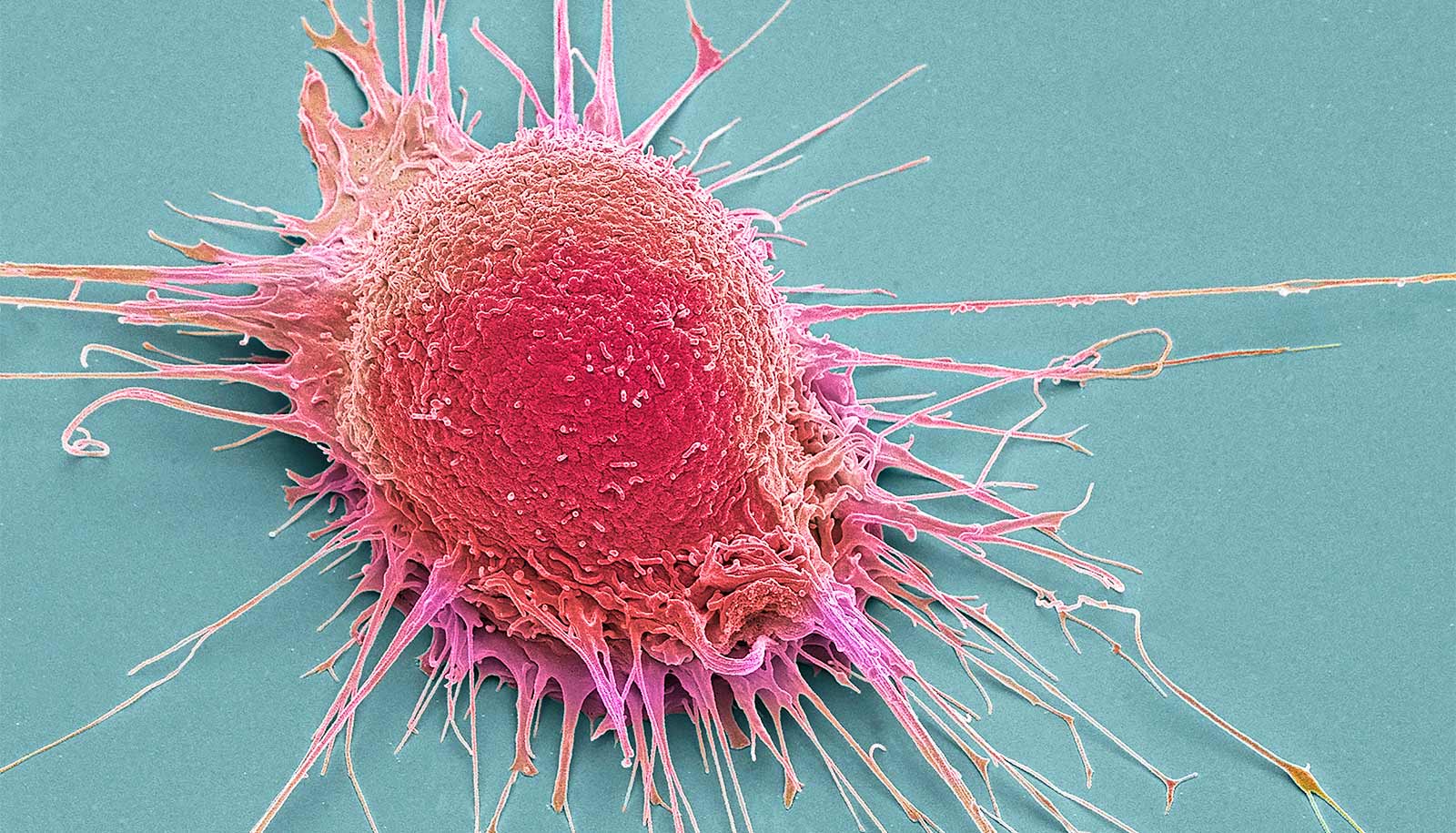

“We’re studying collective sensing, but this is also important in collective movement, as you would see in embryonic development, wound healing, and in cancer. We’re learning that the way disease plays out often has a great deal to do with multicellular effects.

“As cells go from a tumor-like state to a metastatic state, reaching other parts of the body often requires coordinated action. Cells leave the tumor and enter the bloodstream, and for certain cancers, this is a collective process.”

The journal Physical Review Letters has published the study, which the Simons Foundation funded.

Source: Purdue University