A new method using 3D-printed cell traps can separate cancer cells from billions of blood cells in a patient sample, researchers report.

Trapping the white blood cells—which are about the size of cancer cells—and filtering out smaller red blood cells leaves behind the tumor cells, which could be useful in diagnosing disease, potentially provide early warning of recurrence, and enable research into the cancer metastasis process.

The work could advance the goal of personalized cancer treatment by allowing rapid and low-cost separation of tumor cells circulating in the bloodstream.

“Isolating circulating tumor cells from whole blood samples has been a challenge because we are looking for a handful of cancer cells mixed with billions of normal red and white blood cells,” says A. Fatih Sarioglu, an assistant professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology.

“With this device, we can process a clinically-relevant volume of blood by capturing nearly all of the white blood cells and then filtering out the red blood cells by size. That leaves us with undamaged tumor cells that can be sequenced to determine the specific cancer type and the unique characteristics of each patient’s tumor.”

Better than other tech

Other attempts to capture circulating tumor cells have attempted to extract them from the blood using microfluidic technology that recognizes specific surface markers on the cancer cells. But because the cancer can change over time, the technology can’t recognize malignant cells with certainty. And even if it can capture them, the tumor cells must be removed from circuitous channels in the device and separated from the antigen without causing damage.

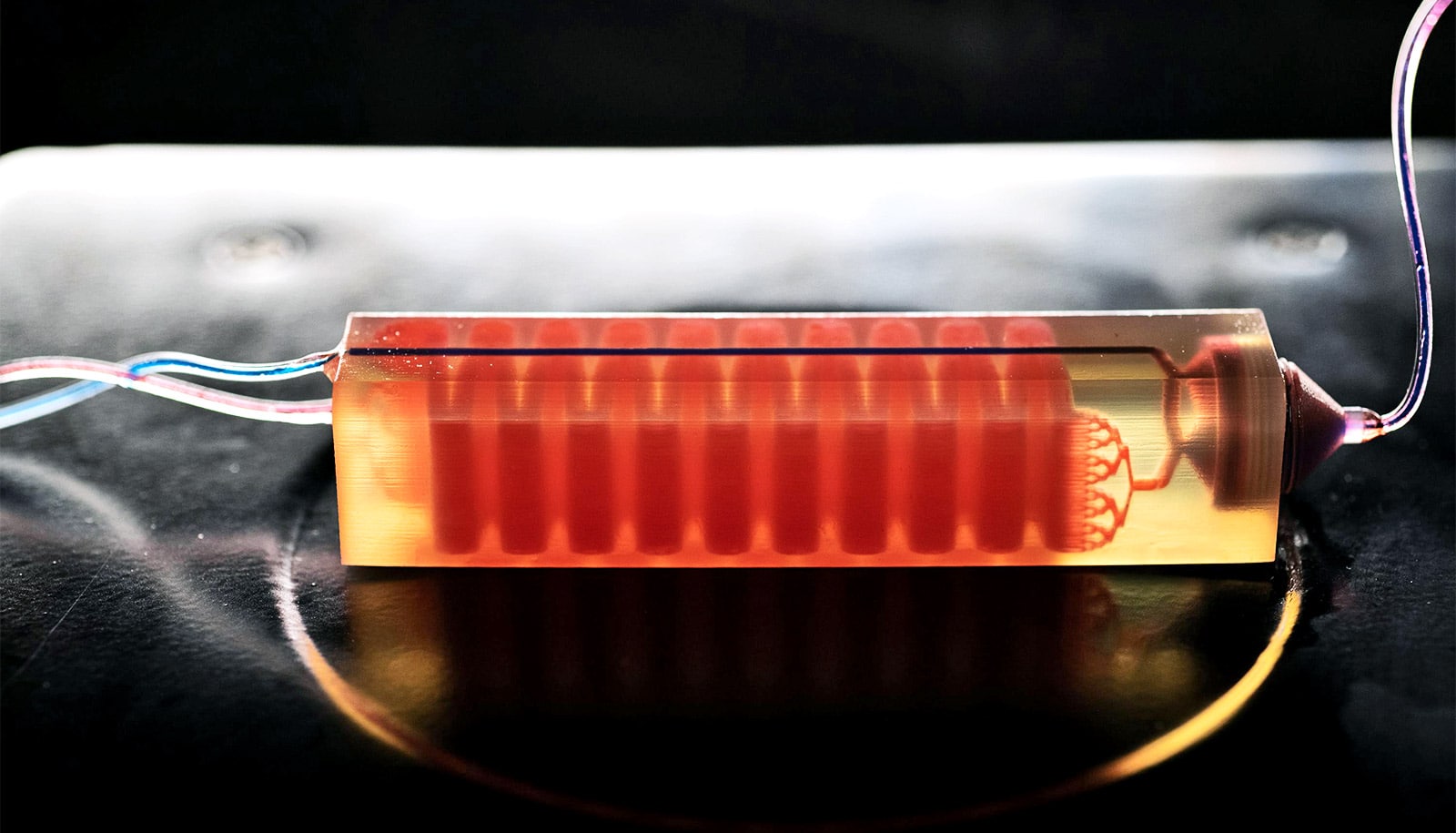

Sarioglu and collaborators, including graduate student and first author Chia-Heng Chu, decided to take a different approach, building 3D-printed traps lined with antigens to capture the white blood cells in a sample. The 3D printed traps allowed the researchers to greatly expand the surface area for capturing the white blood cells as they pass by in blood samples. Zig-zagging fluid channels, some as much as half a meter long, increase the likelihood that every white blood cell would come into contact with a channel wall.

“Usual microfluidic devices have just a single layer with channel heights of 50 to 100 microns,” Sarioglu says. “They are thick, but most of it just empty plastic. Using 3D printing liberates us from the single channel and allows us to create many channels in three dimensions that better utilize the space.”

Issues with 3D printing

While the 3D printing allowed an increase in channel density, that came with a significant challenge. Researchers could design earlier microfluidic devices with etched channels to carry the blood. But with 3D printing processes that are fabricated layer-by-layer, channels had to be filled with wax to allow more channels to be built atop them. The torturous channel structure, designed to maximize cell-wall interaction, made it virtually impossible to get the wax out after fabrication.

The researchers’ solution was to design cell traps that fit into standard centrifuges designed to spin samples for separation. They heated the traps in the centrifuge and then spun them to allow the melted wax to escape. After removing the liquid wax, the channels received the antigen coating.

After the white blood cells are removed, the smaller red blood cells pass through a simple commercial filter that traps the cancer cells and any remaining white blood cells. The tumor cells can then be removed from the filter, which is integrated into the 3D printed device.

Minimal processing of blood samples is a goal for the project to make the process available to clinics and hospitals without requiring specialized technician skills. Less processing also reduces the risk of damage to the tumor cells and minimizes other cellular changes that could skew the evaluation.

As part of the proof of principle testing, the researchers coated the white blood cells with biotin to accelerate testing. Future cell traps will use antigens designed to attract the cells to the channel walls without the biotin processing step.

Cancer cells in a haystack

The researchers tested their approach by adding cancer cells to blood from healthy people. Because they knew how many cells were added, they could tell how many they should extract, and the experiment showed the trap could capture around 90% of the tumor cells. Later testing of blood samples from prostate cancer patients isolated tumor cells from a 10-milliliter whole blood sample.

Testing included cells from prostate, breast, and ovarian cancer, but Sarioglu believes that the device will capture circulating tumor cells from any type of cancer because the removal mechanism targets blood cells rather than cancer cells.

The next steps will be to narrow the channels in the device, test white blood cell removal without the use of biotin, boost the percentage of white cell extraction, and connect cell traps to increase trapping capacity.

“We expect that this will really be an enabling tool for clinicians,” Sarioglu says. “In our lab, the mindset is always toward translating our research by making the device simple enough to be used in hospitals, clinics, and other facilities that will help diagnose disease in patients.”

The research appears in the journal Lab on a Chip.

Support for the work came from the Integrated Cancer Research Center at Georgia Tech. Additional coauthors are from Georgia Tech and Emory University.

Source: Georgia Institute of Technology