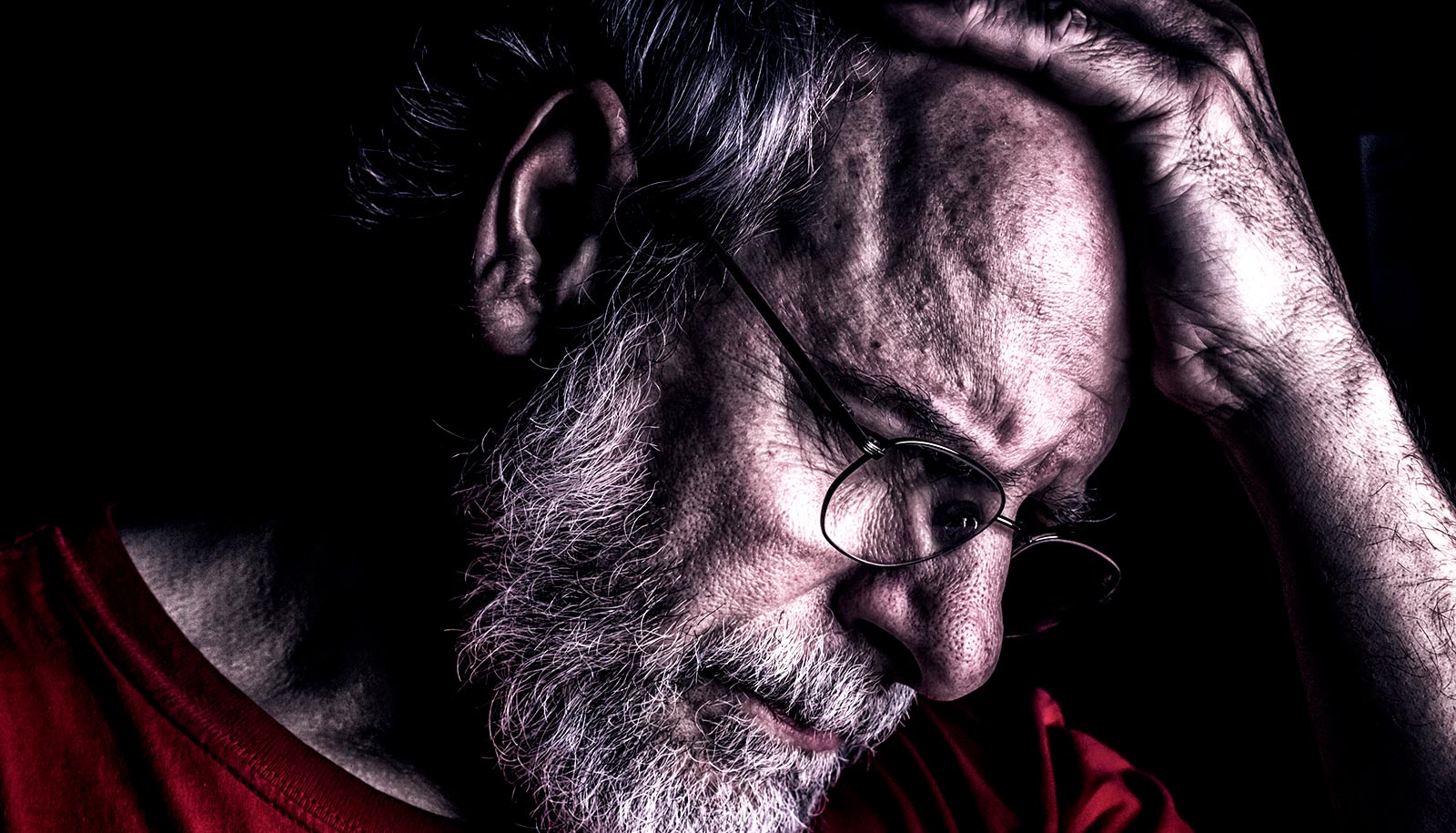

Researchers have come up with a new method of diagnosing cancer in its early stages in humans by way of a malaria protein—VAR2CSA—that sticks to cancer cells. All the scientists need to determine whether or not a person has cancer is a blood sample.

Each year, cancer kills approximately nine million people worldwide, and early diagnosis is crucial to efficient treatment and survival.

“…if there is a cancer cell in your blood, you have a tumor somewhere in your body.”

“We have developed a method where we take a blood sample and with great sensitivity and specificity, we’re able to retrieve the individual cancer cells from the blood,” says Ali Salanti from the immunology and microbiology department at the University of Copenhagen and joint author of the study, which has just been published in the journal Nature Communications.

“We catch the cancer cells in greater numbers than existing methods, which offers the opportunity to detect cancer earlier and thus improve outcome,” Salanti says. “You can use this method to diagnose broadly, as it’s not dependent on cancer type. We have already detected various types of cancer cells in blood samples. And if there is a cancer cell in your blood, you have a tumor somewhere in your body.”

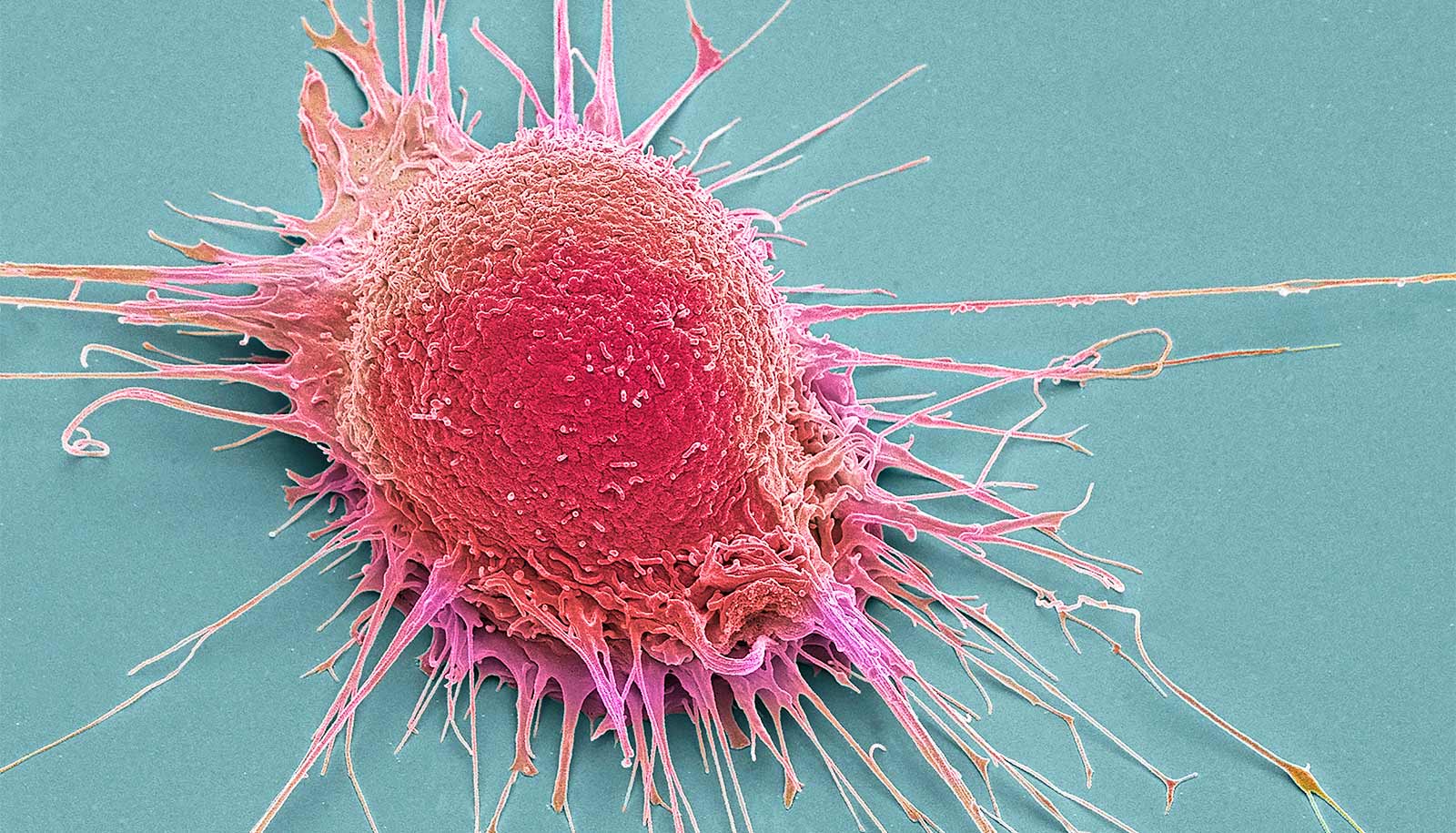

Today, there are several ways of detecting cancer cells in blood. Most of them are based on a particular marker on the surface of tumor cells. However, not all tumor cells display this marker, which renders these methods unable to detect tumor cells spread to other organs such liver, lung, and bones, as opposed to the method based on the malaria protein.

A few years ago, Ali Salanti and his fellow researchers discovered a new method of treating cancer with the protein VAR2CSA, which malaria parasites produce. And these discoveries form the basis of the research group’s new method of diagnosis.

Among other findings, they researchers have shown that the malaria protein sticks to a specific sugar molecule, which is in more than 95 percent of all types of cancer cells. In other words, this new method of diagnosis can detect practically all types of cancer.

Cancer cells in the blood

A cancerous tumor consists of several different cancer cells, some of which spread by wandering through the tissue and into the blood. These cancer cells in the blood are called circulating tumor cells, and they can develop into metastases, which cause up to 90 percent of all cancer-related deaths. If cancer originating in the lungs spreads to the brain, it is called brain metastasis.

The researchers retrieve these circulating tumor cells from blood samples with the malaria protein. During the development of this new method, the researchers took 10 cancer cells and added them to five milliliters of blood, and subsequently, they were able to retrieve nine out of 10 cancer cells from the blood sample.

Despite risks, many Americans want cancer screenings

“We count the number of cancer cells and based on that we’re able to make a prognosis. You can, for example, decide to change a given treatment if the number of circulating tumor cells does not change during the treatment the patient is currently undergoing,” says study coauthor Mette Ørskov Agerbæk, a postdoctoral researcher in the immunology and microbiology department.

“This method also enables us to retrieve live cancer cells, which we can then grow and use for testing treatments in order to determine which type of treatment the patient responds to.”

Testing the blood test

The researchers followed up their results with a large clinical study where they tested many more patients with cancer of the pancreas using the new method.

“We found strikingly high numbers of circulating tumor cells in every single patient with pancreatic cancer, but none in the control group,” says coauthor Christopher Heeschen, a professor in the School of Medical Sciences at UNSW Sydney in Australia.

The researchers envision being able to use the method to screen people at high risk of developing cancer in the future. However, they also expect that this method can be a biomarker indicating whether a patient with mostly vague symptoms indeed has cancer or not. This will enable doctors to determine the stage of the disease.

“Today, it’s difficult to determine which stage cancer is at. Our method has enabled us to detect cancer at stages one, two, three, and four. Based on the number of circulating tumor cells we find in someone’s blood, we’ll be able to determine whether it’s a relatively aggressive cancer or not so then to adjust the treatment accordingly,” explains Salanti, who adds that a much larger clinical study is necessary before the researchers can make firm correlations to tumor staging.

Young women get earlier cancer diagnoses under Obamacare

Some of the researchers behind the study have previously submitted a patent application for the use of the diagnosis method described in the new study. Salanti has worked with and studied the malaria protein for a number of years, which has led to several spinout companies, including the biotech company VAR2pharmaceuticals, where they work on developing cancer medication using the malaria protein.

Salanti and the researchers behind the malaria protein, as well as the University of Copenhagen, own and founded the company.

The European Research Council (ERC), the Danish Cancer Society, VAR2Pharmaceuticals, Harboefonden, Aase og Ejner Danielsens Fonden, Kirsten og Freddy Johansens Fond, Sven Andersen Fonden, Agnes og Poul Friis Fond, the Danish Research Councils, and the Danish Innovation Foundation supported the research. Mette Ørskov Agerbæk, Ali Salanti, and four more researchers involved in the new study have shares in VAR2Pharmaceuticals.

Source: University of Copenhagen