A new app could let people easily screen themselves for pancreatic cancer and other diseases, all by snapping a selfie with their smartphone.

Pancreatic cancer has one of the worst prognoses—with a five-year survival rate of 9 percent—in part because there are no telltale symptoms or non-invasive screening tools to catch a tumor before it spreads.

BiliScreen uses a smartphone camera, computer vision algorithms, and machine learning tools to detect increased bilirubin levels in a person’s sclera, or the white part of the eye.

One of the earliest symptoms of pancreatic cancer, as well as other diseases, is jaundice, a yellow discoloration of the skin and eyes caused by a buildup of bilirubin in the blood. The ability to detect signs of jaundice when bilirubin levels are minimally elevated—but before they’re visible to the naked eye—could enable an entirely new screening program for at-risk individuals.

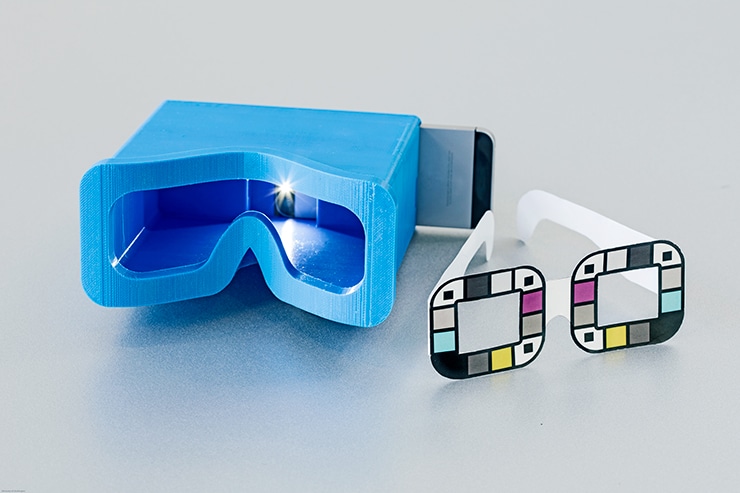

In an initial clinical study of 70 people, the BiliScreen app—used in conjunction with a 3D printed box that controls the eye’s exposure to light—correctly identified cases of concern 89.7 percent of the time, compared to the blood test currently used.

“The problem with pancreatic cancer is that by the time you’re symptomatic, it’s frequently too late,” says lead author Alex Mariakakis, a doctoral student at the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington.

“The hope is that if people can do this simple test once a month—in the privacy of their own homes—some might catch the disease early enough to undergo treatment that could save their lives,” he says.

BiliScreen builds on earlier work from the university’s Ubiquitous Computing Lab, which previously developed BiliCam, a smartphone app that screens for newborn jaundice by taking a picture of a baby’s skin. A recent study in the journal Pediatrics showed BiliCam provided accurate estimates of bilirubin levels in 530 infants.

“The eyes are a really interesting gateway into the body…”

The blood test that doctors currently use to measure bilirubin levels—which is typically not administered to adults unless there is reason for concern—requires access to a health care professional and is inconvenient for frequent screening.

BiliScreen is designed to be an easy-to-use, noninvasive tool that could help determine whether someone ought to consult a doctor for further testing. Beyond diagnosis, BiliScreen could also potentially ease the burden on patients with pancreatic cancer who require frequent bilirubin monitoring.

“The eyes are a really interesting gateway into the body…”

In adults, the whites of the eyes are more sensitive than skin to changes in bilirubin levels, which can be an early warning sign for pancreatic cancer, hepatitis, or the generally harmless Gilbert’s syndrome. Unlike skin color, changes in the sclera are more consistent across all races and ethnicities.

Yet, by the time people notice the yellowish discoloration in the sclera, bilirubin levels are already well past cause for concern. The research team wondered if computer vision and machine learning tools could detect those color changes in the eye before humans can see them.

“The eyes are a really interesting gateway into the body—tears can tell you how much glucose you have, sclera can tell you how much bilirubin is in your blood,” says senior author Shwetak Patel, a professor of computer science and engineering as well as electrical engineering.

DNA blood test may spot cancer early

“Our question was: Could we capture some of these changes that might lead to earlier detection with a selfie?”

BiliScreen uses a smartphone’s built-in camera and flash to collect pictures of a person’s eye as they snap a selfie. The team developed a computer vision system to automatically and effectively isolate the white parts of the eye, which is a valuable tool for medical diagnostics. The app then calculates the color information from the sclera—based on the wavelengths of light that are being reflected and absorbed—and correlates it with bilirubin levels using machine learning algorithms.

To account for different lighting conditions, the team tested BiliScreen with two different accessories: paper glasses printed with colored squares to help calibrate color and a 3D-printed box that blocks out ambient lighting. Using the app with the box accessory—reminiscent of a Google Cardboard headset—led to slightly better results.

Next steps for the research team include testing the app on a wider range of people at risk for jaundice and underlying conditions, as well as continuing to make usability improvements—including removing the need for accessories like the box and glasses.

“This relatively small initial study shows the technology has promise,” says coauthor Jim Taylor, a professor in the department of pediatrics at the university’s medical school whose father died of pancreatic cancer at age 70.

Most doctors don’t share pros and cons of prostate screening

“Pancreatic cancer is a terrible disease with no effective screening right now,” Taylor says. “Our goal is to have more people who are unfortunate enough to get pancreatic cancer to be fortunate enough to catch it in time to have surgery that gives them a better chance of survival.”

The new app is described in a paper to be presented September 13 at Ubicomp 2017, the Association for Computing Machinery’s International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing.

The National Science Foundation, the Coulter Foundation, and endowment funds from the Washington Research Foundation funded the research.

Source: University of Washington