Researchers have engineered bacteria to quickly sense and report on the presence of a variety of contaminants in the environment.

Their study in Nature shows the cells can be programmed to identify chemical invaders and report within minutes by releasing a detectable electrical current.

Such “smart” devices could power themselves by scavenging energy in the environment as they monitor conditions in settings like rivers, farms, industry, and wastewater treatment plants and to ensure water security, according to the researchers.

The environmental information communicated by these self-replicating bacteria can be customized by replacing a single protein in the eight-component, synthetic electron transport chain that gives rise to the sensor signal.

“I think it’s the most complex protein pathway for real-time signaling that has been built to date,” says Jonathan (Joff) Silberg, director of Rice University’s Systems, Synthetic, and Physical Biology PhD Program, a professor of biosciences, and a professor of bioengineering. “To put it simply, imagine a wire that directs electrons to flow from a cellular chemical to an electrode, but we’ve broken the wire in the middle. When the target molecule hits, it reconnects and electrifies the full pathway.”

“It’s literally a miniature electrical switch,” says Caroline Ajo-Franklin, a professor of biosciences at Rice.

“You put the probes into the water and measure the current,” she says. “It’s that simple. Our devices are different because the microbes are encapsulated. We’re not releasing them into the environment.”

The researchers’ proof-of-concept bacteria was Escherichia coli, and their first target was thiosulfate, a dichlorination agent used in water treatment that can cause algae blooms. And there were convenient sources of water to test: Galveston Beach and Houston’s Brays and Buffalo bayous.

They collected water from each. At first, they attached their E. coli to electrodes, but the microbes refused to stay put. “They don’t naturally stick to an electrode,” Ajo-Franklin says. “We’re using strains that don’t form biofilms, so when we added water, they’d fall off.”

When that happened, the electrodes delivered more noise than signal.

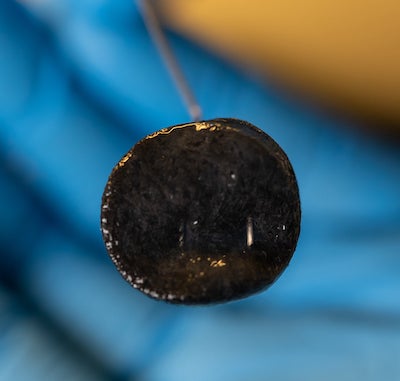

Enlisting coauthor Xu Zhang, a postdoctoral researcher in Ajo-Franklin’s lab, they encapsulated sensors into agarose in the shape of a lollipop that allowed contaminants in but held the sensors in place, reducing the noise.

“Xu’s background is in environmental engineering,” Ajo-Franklin says. “She didn’t come in and say, ‘Oh, we have to fix the biology.’ She said, ‘What can we do with the materials?’ It took great, innovative work on the materials side to make the synthetic biology shine.”

With the physical constraints in place, the labs first encoded E. coli to express a synthetic pathway that only generates current when it encounters thiosulfate. This living sensor was able to sense this chemical at levels less than 0.25 millimoles per liter, far lower than levels toxic to fish.

In another experiment, E. coli was recoded to sense an endocrine disruptor. This also worked well, and the signals were greatly enhanced when conductive nanoparticles custom-synthesized by Rice graduate Lin Su were encapsulated with the cells in the agarose lollipop. The researchers reported these encapsulated sensors detect this contaminant up to 10 times faster than the previous state-of-the-art devices.

The study began by chance when Josh Atkinson, a visiting National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow at Aarhus University, Denmark, and Moshe Baruch of Ajo-Franklin’s group at Berkeley Lawrence National Laboratory set up next to each other at a 2015 synthetic biology conference in Chicago, with posters they quickly realized outlined different aspects of the same idea.

“We had neighboring posters because of our last names,” says Atkinson. “We spent most of the poster session chatting about each other’s projects and how there were clear synergies in our interests in interfacing cells with electrodes and electrons as an information carrier.”

“Josh’s poster had our first module: how to take chemical information and turn it into biochemical information,” Ajo-Franklin recalled. “Moshe had the third module: How to take biochemical information and turn it into an electrical signal.

“The catch was how to link these together,” she says. “The biochemical signals were a little different.”

“We said, ‘We need to get together and talk about this!'” Silberg recalls. Within six months, the new collaborators won seed funding from the Office of Naval Research, followed by a grant, to develop the idea.

“Joff’s group brought in the protein engineering and half of the electron transfer pathway,” Ajo-Franklin says. “My group brought the other half of the electron transport pathway and some of the materials efforts.”

“We have to give so much credit to Lin [Su] and Josh,” she says. “They never gave up on this project, and it was incredibly synergistic. They would bounce ideas back and forth and through that interchange solved a lot of problems.”

“Each of which another student could spend years on,” Silberg adds.

“Both Josh and I spent several years of our PhDs working on this, with the pressure of graduating and moving on to the next stage of our careers,” says Su, a visiting graduate student in Ajo-Franklin’s lab after graduating from Southeast University in China. “I had to extend my visa multiple times to stay and finish the research.”

Silberg says the design’s complexity goes far beyond the signaling pathway. “The chain has eight components that control electron flow, but there are other components that build the wires that go into the molecules,” he says. “There are a dozen-and-a-half components with almost 30 metal or organic cofactors. This thing’s massive compared to something like our mitochondrial respiratory chains.”

Silberg says he sees engineered microbes performing many tasks in the future, from monitoring the gut microbiome to sensing contaminants like viruses, improving upon the successful strategy of testing wastewater plants for SARS-CoV-19 during the pandemic.

“Real-time monitoring becomes pretty important with those transient pulses,” he says. “And because we grow these sensors, they’re potentially pretty cheap to make.”

To that end, the team is collaborating with Rafael Verduzco, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and of materials science and nanoengineering.

“The type of materials we can make with Raphael takes this to a whole new level,” Ajo-Franklin says.

Silberg says the labs are working on design rules to develop a library of modular sensors. “I hope that when people read this, they recognize the opportunities,” he says.

Support for the research came from the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy; the Office of Naval Research; the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas; the National Science Foundation; the Department of Energy Office of Science Graduate Student Research Program; the Lodieska Stockbridge Vaughn Fellowship; and the China Scholarship Council Fellowship.

Source: Rice University