The swelling caused by a byproduct of amyloid plaques in the brain may be the true cause of Alzheimer’s disease, say researchers.

Their work, published in Nature, also identifies a biomarker that may help physicians better diagnose Alzheimer’s disease and provide a target for future therapies.

The formation of amyloid plaques in the brain is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. But drugs designed to reduce accumulations of these plaques have so far yielded, at best, mixed results in clinical trials.

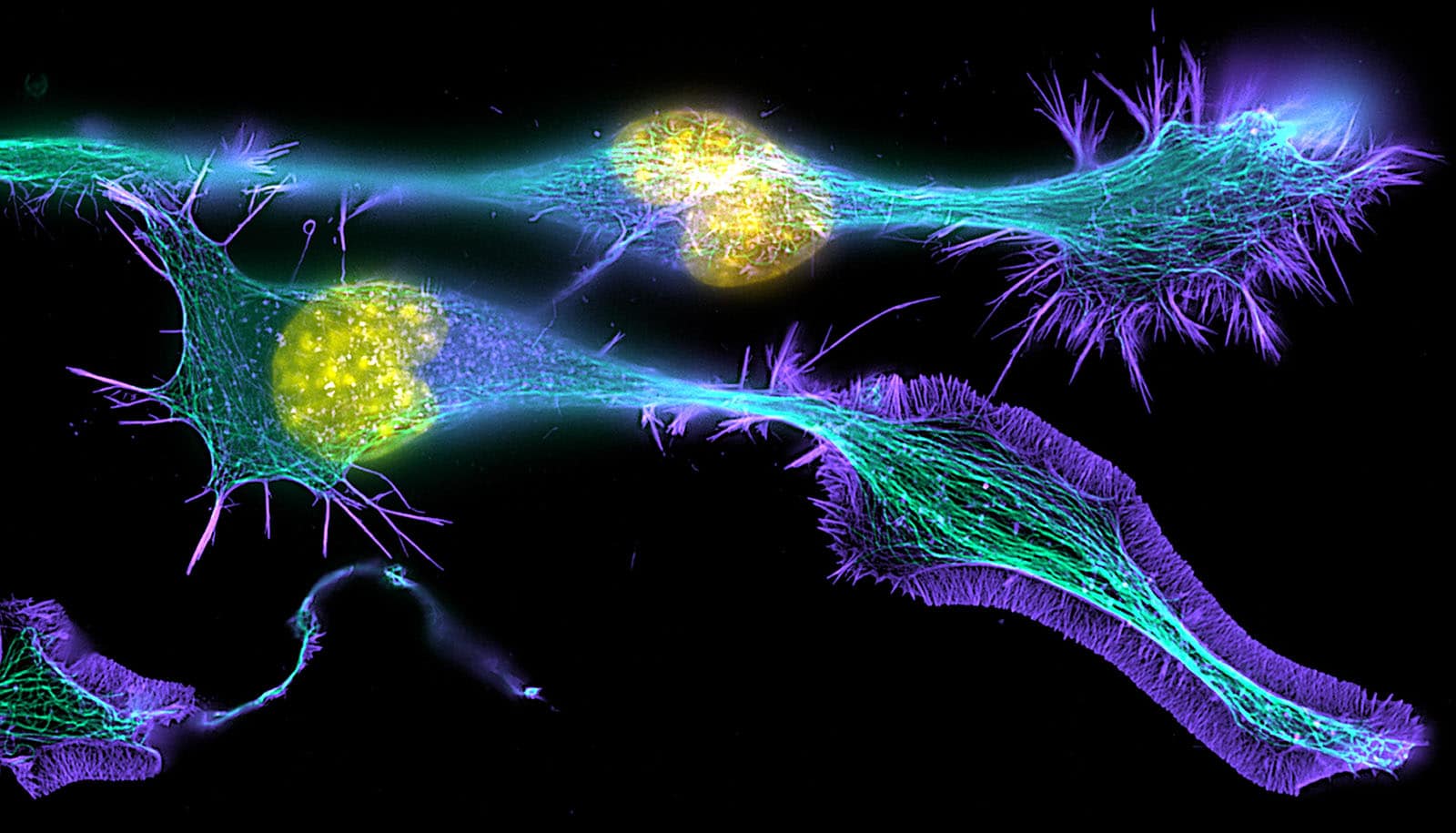

According to the new findings, each formation of plaque can cause an accumulation of spheroid-shaped swellings along hundreds of axons—the thin cellular wires that connect the brain’s neurons—near amyloid plaque deposits. The swellings are caused by the gradual accumulation of organelles within cells known as lysosomes, which are known to digest cellular waste, researchers find. As the swellings enlarge, researchers say, they can blunt the transmission of normal electrical signals from one region of the brain to another.

This pileup of lysosomes, the researchers say, causes swelling along axons, which in turn triggers the devastating effects of dementia.

“We have identified a potential signature of Alzheimer’s which has functional repercussions on brain circuitry, with each spheroid having the potential to disrupt activity in hundreds of neuronal axons and thousands of interconnected neurons,” says Jaime Grutzendler, professor of neurology and neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine and senior author of the study.

Further, the researchers discovered that a protein in lysosomes called PLD3 caused these organelles to grow and clump together along axons, eventually leading to the swelling of axons and the breakdown of electrical conduction.

When they used gene therapy to remove PLD3 from neurons in mice with a condition resembling Alzheimer’s disease, they found that this led to a dramatic reduction of axonal swelling. This, in turn, normalized the electrical conduction of axons and improved the function of neurons in the brain regions linked by these axons.

The researchers say PLD3 may be used as a marker in diagnosing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and provide a target for future therapies.

“It may be possible to eliminate this breakdown of the electrical signals in axons by targeting PLD3 or other molecules that regulate lysosomes, independent of the presence of plaques,” Grutzendler says.

Source: Yale University