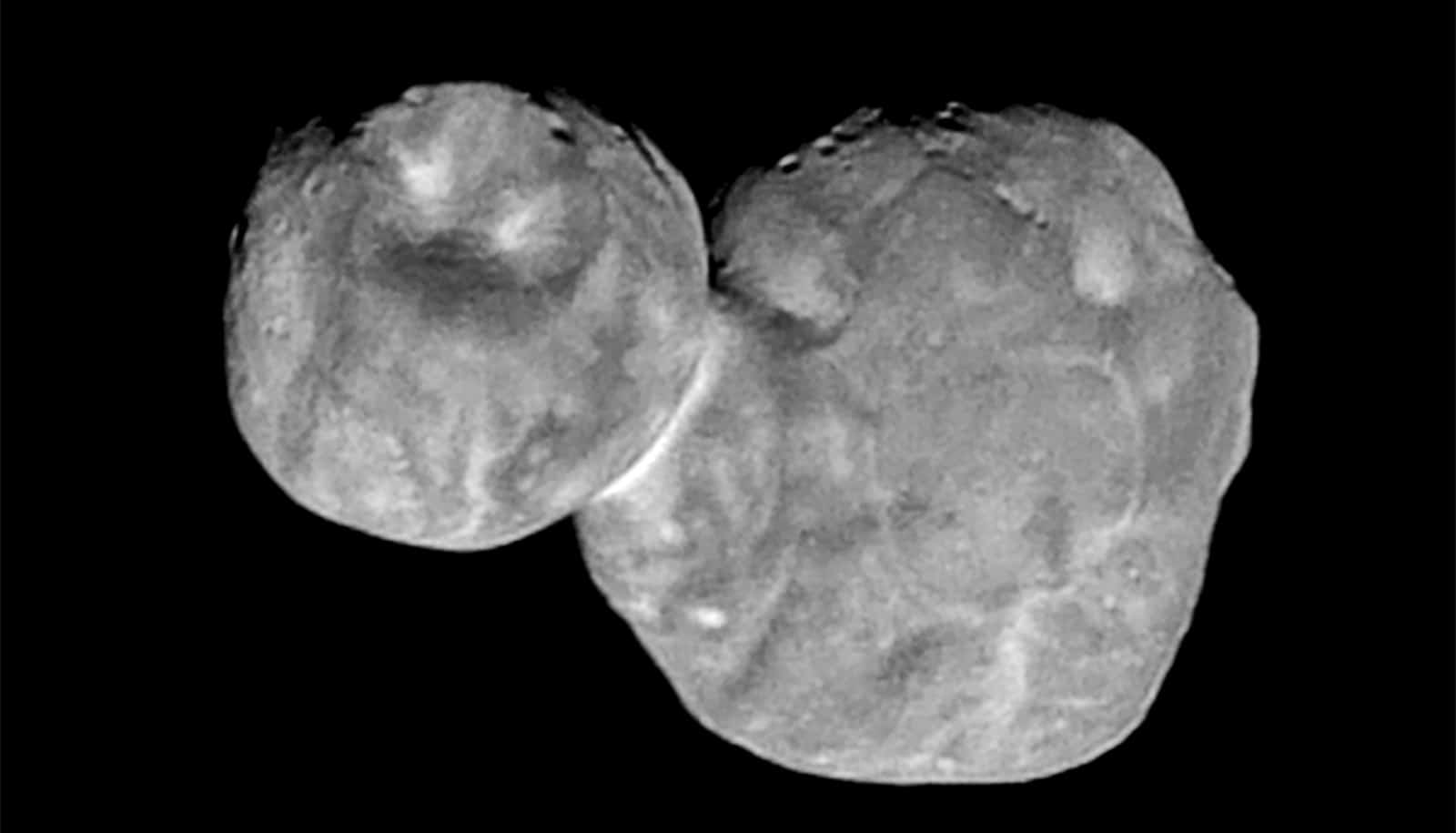

New research describes the farthest, most primitive object in the solar system a spacecraft has ever visited—a bi-lobed Kuiper Belt object known as Arrokoth.

The reports expand upon the first published results on this object. Those previous results were based on a small amount of initial data from the New Horizons spacecraft after a January 2019 flyby.

William B. McKinnon, professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, is a co-investigator on the New Horizons mission and the first author of one of the three new papers, all of which appear in Science.

“Just as fossils tell us how species evolved on Earth, planetesimals tell us how planets formed in space.”

Researchers based the new reports on over 10 times as much data from that flyby. Taken together, they provide a far more complete picture of the composition and origin of Arrokoth. They also point to the resolution of a longstanding scientific controversy about how such primitive planetary building blocks called planetesimals were formed.

For their portion of the work, McKinnon and colleagues used simulations to better understand how Arrokoth formed.

Their analysis indicates that the two lobes were previously independent bodies formed close together and assembled into the present-day object very gently. The finding points to formation in a local particle cloud of the solar nebula and not by the other longstanding theory of planetesimal formation, called hierarchical accretion, in which objects from disparate parts of the nebula collided to form the object over an extended time span.

“Just as fossils tell us how species evolved on Earth, planetesimals tell us how planets formed in space,” McKinnon says. “Arrokoth looks the way it does not because it formed through violent collisions, but in more of an intricate dance, in which its component objects slowly orbited each other before coming together.”

Other researchers also presented two studies based on the new results from the close-up images of Arrokoth, which means “sky” in the Powhatan/Algonquian language.

One study investigated the shape and volume of Arrokoth’s lobes and uses crater density to infer the age of its surface at about 4 billion years or more. The other study examined the uniform color and composition of Arrokoth’s surface. These studies also support the discovery that Arrokoth was formed in a collapsing, local solar nebula particle cloud.

McKinnon presented these results at the 2020 American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Seattle. You can see the full briefing materials the researchers shared here.