The majority of app-based drivers report high levels of stress and concern about exposure to COVID-19, a survey finds. Roughly 30% thought they had already had the virus.

Drivers face a number of concerns: Is this passenger ill? Are they properly masked? Will they pull it down once seated? Will they cough, blowing air around? Are they in a bad mood? Did they just get out of a rough meeting or a fight at a bar?

“It’s a job that is vital to so many people, for moving people to and from medical appointments, to and from the airport, etc. Obviously, app-based drivers are essential for moving people,” says Marissa Baker, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington. “It’s vital work, but it’s largely something the general public seems to forget about.”

Baker is senior author of a new study in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine that focuses on understanding the pressures, risks, and dilemmas facing app-based drivers during the pandemic.

Every ride carries potential risks. Each trip includes at least two people—possible disease vectors, unpredictable humans—now in a closed and confined space. The passenger may face this risk a few times a week. For the driver, this is a workplace risk possibly undertaken dozens of times a day.

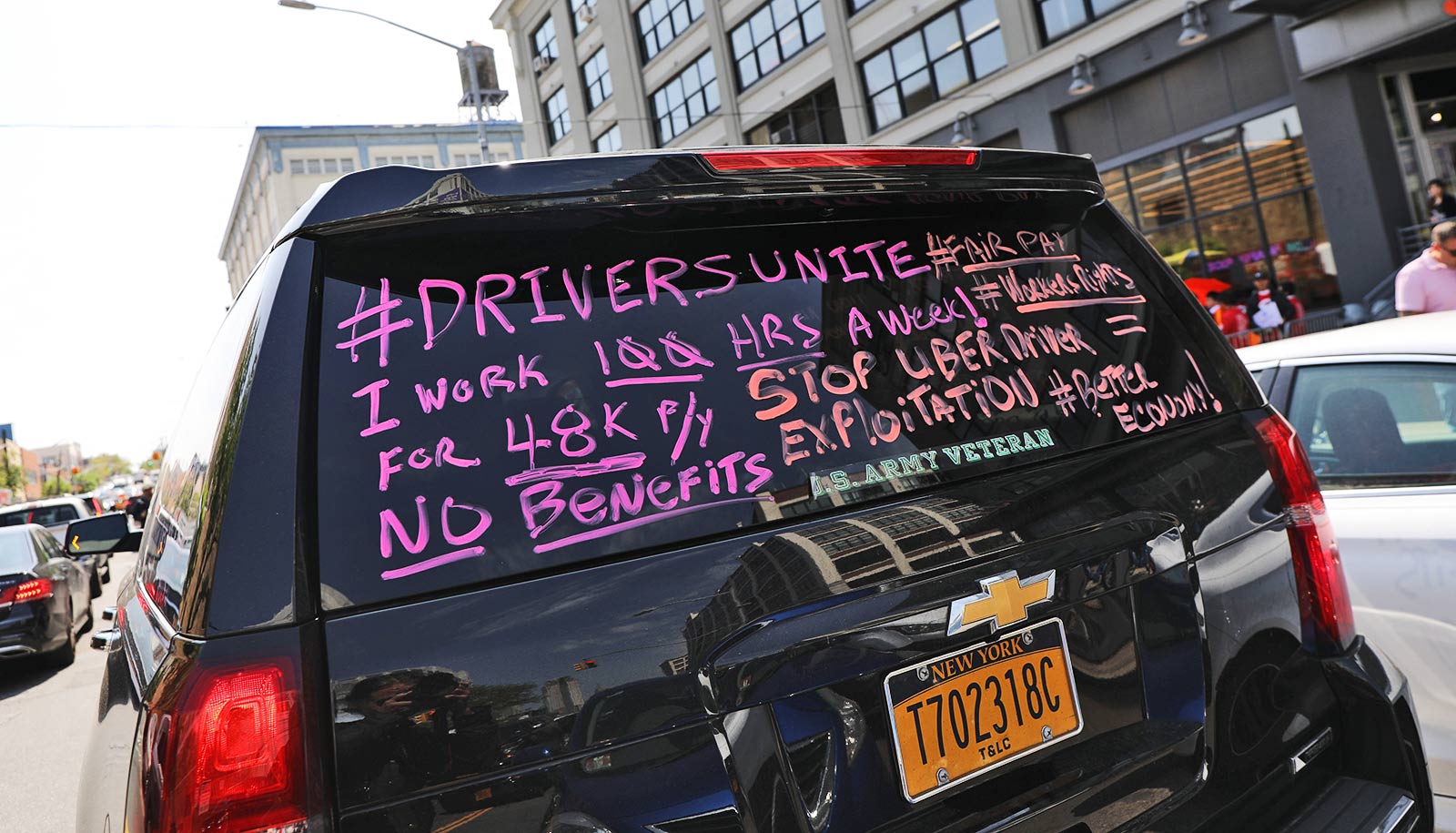

Throw a viral pandemic into the mix, and you have workers in a largely unprotected job facing a range of very difficult choices: keep driving no matter what or lose income; ignore an improperly masked passenger or tell them to mask up and risk a bad review or altercation; drive a coughing passenger to a COVID-19 testing site or face deactivation for turning them away; pay out-of-pocket for cleaning supplies and PPE or run an even greater risk of infection.

100 app-based drivers

To illuminate these pressures, Baker and colleagues trained four app-based drivers, all affiliated with the Teamsters Local 117 in Seattle, to conduct survey interviews of their fellow drivers. The newly trained interviewers surveyed 100 app-based drivers in Seattle between August 11 and September 7, 2020. The drivers were predominantly male (97%), identified as Black or African (84%), and were under the age of 55 (87%).

The majority of drivers reported high levels of stress and concern about being exposed to the novel coronavirus. Roughly 30% thought they had already had COVID-19. Most, 73 drivers, lost income, while spending their own money on PPE. Those who left the business because of the pandemic (42 drivers) reported having a hard time getting unemployment benefits. Only 31% said they received an appropriate mask and hand sanitizer from the company they drove for, and even then the supplies were not enough.

“For workers who are in this kind of employment during the pandemic, they receive very little support from the companies that they drive for, and this is a population that had a lot of awareness of the potential exposures they could be facing,” Baker says. “They had a lot of concerns and worries, not only about how those exposures would be affecting their health and their family’s health, but also the viability and their job.”

Isolated workers can’t organize

The drivers spoke of feeling isolated and lonely, since they rarely have a chance to talk with their peers.

In the study, one driver explained, “[I]n this line of work, you’re very insular. I mean, I’m in my own little universe… so finding a way to bridge that gap has been the biggest challenge.”

Simple issues, like finding restrooms, became bigger problems with libraries, community centers, and businesses closed during shutdowns.

“You have other people who are doing the same job as you, but you may never interact with them. So you miss out on some of that strength, not only brainstorming of like, ‘Hey what masks are you using?’ or ‘Where are you stopping?’ but it also keeps workers from organizing,” Baker says. “If you get these workers talking to each other and recognizing that they are all facing the same struggles, that can lead to changes.”

Advances in Seattle

In Seattle, drivers and their union leaders have been able to win a minimum wage requirement as well as establish a “resolution center” where drivers contest being taken off the apps through which they are hired. There have been other improvements as well in Seattle and other cities.

Baker explains that while Seattle has taken steps to try to improve drivers’ working conditions, drivers nationwide do not enjoy the same benefits because they are not classified as employees. So, they don’t have access to state or federal health and safety protections, a living wage, or sick leave.

“This is a full-time job for many people, this is not just driving on the weekends to supplement another job. These drivers are raising families, using what they make to pay for their kids to go to college. This is important, vital work, and we should be recognizing that through the benefits that we demand that these drivers receive,” Baker says. “Not only for their well-being, but also for the customers they interact with.”

A UW Population Health Initiative Economic Recovery Grant supported the work.

Source: University of Washington